Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images

From the Internet’s earliest days, US policy makers have been grappling with the question of if or how much the federal government should be involved in regulating the information superhighway.

For more than 16 years, policy makers at the Federal Communications Commission and lawmakers in Congress have worked to strike a balance between protecting consumers’ and innovators’ access to the Internet while also promoting investment from companies interested in building data networks and upgrading them to offer faster and faster speeds.

This week, the FCC takes the latest step in its regulations effort by voting on a set of so-called “Net neutrality” rules. These rules, established under the leadership of FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, a Democrat who was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2013, are designed to make sure that that consumers paying for Internet access will continue to be able to access their favorite websites and apps.

In 1999, the issue wasn’t about Net neutrality as we know it today, which is the concept that consumers should be able to access any legal content they want on the Internet without their Internet service or broadband provider blocking or slowing their access to specific sites or online services. There wasn’t any notion of a fast lane or slow lane on the Internet.

But there was a big question about how the FCC should classify broadband service.

Back then, the problem was that Internet service providers, such as America Online and Prodigy, were able to grow their business because they could access the old telephone network to provide dial-up Internet access. In 1999, as cable operators started to offer Internet service, America Online and others asked for access to the cable networks so they could offer their services over broadband networks as well as through the dial-up Internet, which used the old telephone infrastructure. Remember that scratchy, squealing sound before hearing “You’ve got mail?” That’s the old telephone access to the Internet we’re talking about.

And so began the first debate over whether broadband networks should be treated as as a public utility just like the old-style telephone networks. It took the FCC and the US courts six years to answer this question. And for more than a decade and a half the answer to that question has been “no.”

But 16 years later, the question is being asked again in the latest debate over Net neutrality. On one side, consumer advocates, the FCC’s Wheeler and President Obama, say reclassifying broadband as a public utility-like service is necessary to make sure the FCC has the legal basis to enforce rules protecting an open Internet. An open Internet means no fast lanes or slow lanes of service.

On the other side of the debate are the cable operators and phone companies, like AT&T and Verizon, who say now — as they did in 1999 — that old style regulation will hurt their investment in the infrastructure need to build out the networks through which they deliver Internet service to your computer, smartphone and other gadgets.

Here’s a brief history of how the debate over Net neutrality has played out over time.

July 20, 1999

FCC Chairman William Kennard, a Democrat appointed by President Bill Clinton, set the stage for a light regulatory touch in the Internet’s early days. He was the first FCC chairman to suggest the agency should not subject broadband networks to the same stringent requirements applied to old telephone infrastructure. In an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, he talked up the benefits of “vigilant restraint” on the part of government regulators.

“The Internet is really blossoming, but some policy-makers and politicians want to control it and regulate access to it,” Kennard told the newspaper. “We should not try to intervene in this marketplace. We need to monitor the roll-out but recognize we don’t have all the answers because we don’t know where we’re going.”

March 14, 2002

The FCC, under Republican Chairman Michael Powell, cleared up a question gnawing at the industry: Should cable networks be forced to share their infrastructure with competitors in the same way that telephone operators using older infrastructure were required to allow competitors to use their networks? His answer was “no.” Under Powell’s watch, the FCC classified Broadband Internet Access as a Title I interstate “information service” — not a “telecommunications service” under the 1934 Communications Act. This classification meant that cable broadband services aren’t subject to utility-style, “common carrier” rules.

June 5, 2003

Law professor Tim Wu coined the term “Net neutrality” in his paper “Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination.” This academic paper “examines the the concept of network neutrality in telecommunications policy and its relationship to Darwinian theories of innovation. It also considers the record of broadband discrimination practiced by broadband operators in the early 2000s.”

February 8, 2004

FCC Chairman Michael Powell introduced “Four Internet Freedoms” that he expects the broadband industry to preserve.

- Freedom to access content.

- Freedom to run applications.

- Freedom to attach devices.

- Freedom to obtain service plan information

March 3, 2005

The FCC negotiated an agreement with Madison River Communication over claims it had violated the FCC’s Net neutrality principles. At issue: Madison River Communication, a North Carolina telephone and Internet company the FCC accused of blocking VoIP, or voice over Internet Protoctol, calls. In the agreement with the FCC, Madison River agreed to “refrain from blocking” VoIP traffic. Because it was a negotiated agreement, this is not considered a true FCC enforcement action.

June 27, 2005

In a 6-3 decision led by Justice Clarence Thomas, the Supreme Court overturned a federal appeals court decision that would have forced cable companies to share their infrastructure with Internet service providers.

Here are the details: California-based ISP Brand X had sued the FCC, challenging the agency’s definition of a cable modem service as a Title I “information service” instead of as a Title II “telecommunications service” under the Communications Act. Because of this classification, cable broadband operators weren’t required to share their networks with competing ISPs. Brand X and other Internet service providers argued that cable networks should be treated like telephone lines, on which any ISP could offer services.

The court didn’t answer the question of whether broadband should be classified as an information service or telecommunications service. It just upheld the FCC’s authority to define the classification of broadband. As a result, broadband remained a Title I service under the Communications Act and wasn’t subject to utility-style common carrier requirements.

September 23, 2005

Following the Supreme Court’s Brand X decision, the FCC reclassified Internet access across the phone network, including DSL, as a Title I “information service,” relaxing the common carrier requirement.

September 23, 2005

Republican FCC Chairman Kevin Martin established a “Policy Statement” on Net neutrality using former Chairman Powell’s “Internet Principles” as the foundation. These weren’t official regulation, and therefore the FCC’s enforcement of them was meant to be limited.

The policy included four principles:

- Consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice;

- Consumers are entitled to run applications and services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement;

- Consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network; and

- Consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

November 6, 2005

Ed Whitacre, who became CEO of AT&T after it merged with SBC, stoked the Net neutrality debate when he complained in an interview with BusinessWeek that companies like Google and Yahoo were freeloaders on his company’s infrastructure.

“Now what they would like do is use my pipes for free, but I ain’t going to let them do that because we have spent this capital and we have to have a return on it,” Whitacre told the magazine.

October 19, 2007

After months of speculation, an Associated Press investigative report found that Comcast, the largest cable company in the US, had been blocking or severely delaying traffic using the BitTorrent file-sharing protocol on its network. BitTorrent is used to distribute massive data files, such as high-definition video. The way the protocol works is that rather than downloading a file from a single source server, the BitTorrent protocol allows users to join a “swarm” of hosts to upload to or download from each other simultaneously. While there are legitimate uses for BitTorrent, it has often been associated with the illegal distribution of copyrighted movies and music. In the early and mid-2000s, the use of the technology flooded some networks. As of November 2004, it was believed that BitTorrent traffic was responsible for 35 percent of all Internet traffic. After the AP story was published, consumer advocates accused Comcast of violating the FCC’s Open Internet principles. Comcast claimed it was merely trying to protect its network from being crippled by one type of traffic. The FCC launched an investigation.

March 27, 2008

Comcast and BitTorrent announced an agreement that allowed for Comcast to manage its network without singling out a specific protocol or type of traffic, such as BitTorrent. Instead of singling out BitTorrent traffic when the network was congested, Comcast promised to use network management tactics that did not take traffic type into account. This allowed BitTorrent users to continue using the service without fearing Comcast would slow down their file transfers or any other traffic types when the network was congested.

August 1, 2008

Republican FCC Chairman Kevin Martin sided with the Democrats on the commission in a 3-2 vote, declaring that Comcast’s throttling or slowing down of BitTorrent traffic was unlawful. This was the first and only time the FCC officially found a US broadband provider in violation of Net neutrality principles. The FCC handed Comcast a cease-and-desist order and required the company tell consumers in the future about how it planned to manage traffic.

Martin said the order was meant to set a precedent and signal to Internet service providers that they couldn’t prevent customers from using their networks the way they see fit, unless there’s a good reason.

“We need to protect consumers’ access,” Martin said in a statement at the time. “While Comcast has said it would stop the arbitrary blocking, consumers deserve to know that the commitment is backed up by legal enforcement.”

April 6, 2010

Comcast sued the FCC over the sanction the agency gave it over the BitTorrent issue. And on April 6, 2010, the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit tossed out the FCC’s cease and desist order against Comcast. The court said that the FCC relied on laws that gave it some jurisdiction over regulating broadband services. But the law didn’t give the agency enough authority to take the action it had taken against Comcast.

December 21, 2010

Under Democrat Julius Genachowski, the FCC adopted its Open Internet Order, which for the first time made Net neutrality rules official FCC regulation. The rules prohibited blocking or slowing down access to legal content on the Internet. It required broadband providers to be “transparent” about their network management practices. Mobile networks were also treated differently than wired broadband networks — mobile networks were subject to less stringent rules. These Net neutrality rules didn’t prevent ISPs from charging content companies from additional fees for priority access to their customers. As you would expect, Net neutrality advocates were not happy.

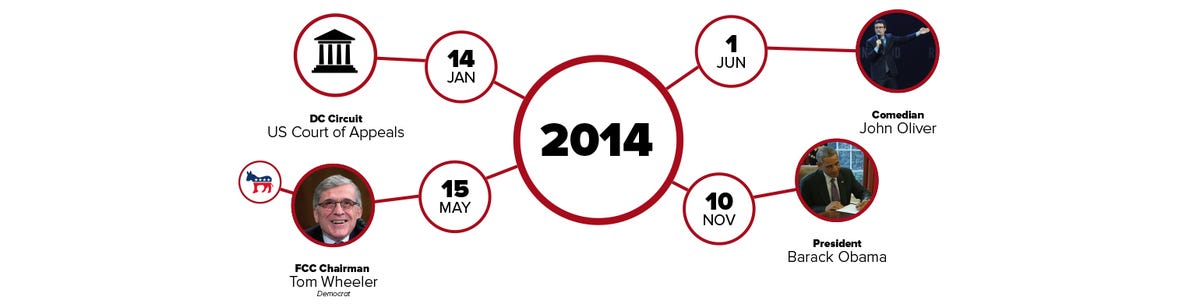

January 14, 2014

The US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit ruled in the case Verizon Communications v. FCC that using the current classification of broadband as a Title I “information service” gave the FCC no authority to adopt Net neutrality regulation based on the concept of “common carriage.” Common carriage is the foundation of regulation for Title II “telecommunications services.”

In a victory for the FCC, the court agreed the FCC should be able to regulate broadband. And it told the agency to come up with rules that better fit the statute.

May 15, 2014

The FCC voted 3-to-2 to open Chairman Wheeler’s controversial proposal to reinstate Net neutrality rules. Wheeler’s proposal ignited a firestorm of protest among consumer advocates who claimed it would let broadband providers create Internet fast lanes.

June 1, 2014

Comedian John Oliver brought the Net neutrality debate to the masses when he aired a 13-minute rant about Net neutrality, imploring Internet trolls to flood the FCC with comments. The FCC received so many comments following his show, they broke the agency’s servers. In total, more than 4 million public comments were filed on the Net neutrality proposal. Among the comments is this gem from Stephen Inzunza:

Hey, I like the internet. I think you like the internet, too…The internet is a tool for expression and social change. Okay, mostly it is for adorable cat photos with captions. Don’t take the cat out of the meow! Or the meow out of the cat? Free porn for all who fight to protect our internet!!!

November 10, 2014

President Obama urged the US government to adopt tighter regulations on broadband service to preserve “a free and open Internet.” He stated his support for reclassifying broadband as a Title II telecommunications service, so that it can be regulated like a utility. This announcement was seen as a turning point in the Net neutrality debate, essentially forcing Chairman Wheeler to push for a solution that required reclassification.

February 26, 2015

The FCC is expected to approve new Net neutrality rules that will reclassify broadband traffic as a Title II telecommunications service. That means broadband providers will be held to many of the requirements of the old telephone network. FCC Chairman Wheeler claims this reclassification of broadband gives the FCC a strong legal case for regulation –a necessity since Verizon and others have already suggested they’ll sue the FCC because they don’t want to be governed by Title II.

This story is part of a CNET special report looking at the challenges of Net neutrality, and what rules — if any — are needed to fuel innovation and protect US consumers.