It’s official. The Internet will now be regulated as a public utility.

After months of anticipation and weeks of frenzied last-minute lobbying on both sides of the political aisle, the Federal Communications Commission has adopted Net neutrality regulations based on a new definition of broadband that will let the government regulate Internet infrastructure as it could the old telephone network.

At the FCC’s monthly meeting Thursday the agency reinstated open Internet rules in a 3-2 vote split along party lines. The new rules replace regulations that had been thrown out by a federal court last year.

The new rules prohibit broadband providers from blocking or slowing down traffic on wired and wireless networks. They also ban Internet service providers from offering paid priority services that could allow them to charge content companies, such as Netflix, fees to access Internet “fast lanes” to reach customers more quickly when networks are congested.

The crux of the new rules is the FCC’s reclassification of broadband as a Title II telecommunications service under the 1934 Communications Act. Applying the Title II moniker to broadband has the potential to radically change how the Internet is governed, giving the FCC unprecedented authority. The provision originally gave the agency the power to set rates and enforce the “common carrier” principle, or the idea that every customer gets equal access to the network. Now this idea will be applied to broadband networks to prevent Internet service providers from favoring one bit of data over another.

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler said the controversial move to reclassify broadband is necessary to ensure that the rules will stand up to future court challenges. The FCC has lost two previous legal challenges when defending its Net neutrality rules.

But the FCC’s move to apply Title II to broadband has been viewed by cable operators, wireless providers and phone companies as a “nuclear option,” with potentially devastating fallout from unintended consequences.

These companies argue that applying outdated regulation to the broadband industry will stifle innovation by hurting investment opportunities in networks. It could also allow the government to impose new taxes and tariffs, which would increase consumer bills. And they say it could even allow the government to force network operators to share their infrastructure with competitors.

Wheeler has said these fears are overblown. The agency is ignoring aspects of the Title II regulation that would apply most of the onerous requirements.

He said critics have painted his proposal as “a secret plan to regulate the Internet.”

His response to that? “Nonsense. This is no more a plan to regulate the Internet than the First Amendment is a plan to regulate free speech. They both stand for the same concept: openness.” Reactions to the passage of the FCC’s new rules and the reclassification of broadband came quick from the industry. Michael Powell, a former FCC chairman and head of the cable industry’s lobbying organization, said the FCC has gone too far in its intent to secure an open Internet for all consumers and entrepreneurs by reclassifying broadband.

“The FCC has taken the overwhelming support for an open Internet and pried open the door to heavy-handed government regulation in a space celebrated for its free enterprise,” he said in a statement. “The Commission has breathed new life into the decayed telephone regulatory model and applied it to the most dynamic, free-wheeling and innovative platform in history.”

AT&T’s top legislative executive, Jim Cicconi, echoed these sentiments in a blog post.

“At AT&T, we’ve supported open Internet principles since they were first enunciated, and we continue to abide by them strictly, and voluntarily, even today,” he said. “What doesn’t make sense, and has never made sense, is to take a regulatory framework developed for Ma Bell in the 1930s and make her great grandchildren, with technologies and options undreamed of 80 years ago, live under it.”

Now playing:

Watch this:

What the FCC Net neutrality rules will mean for Internet…

1:38

Political lines drawn

Thursday’s FCC vote was split along party lines with the three Democrats — led by Wheeler, who was appointed by President Barack Obama — on the five-person commission supporting the proposal and the two Republicans opposing it.

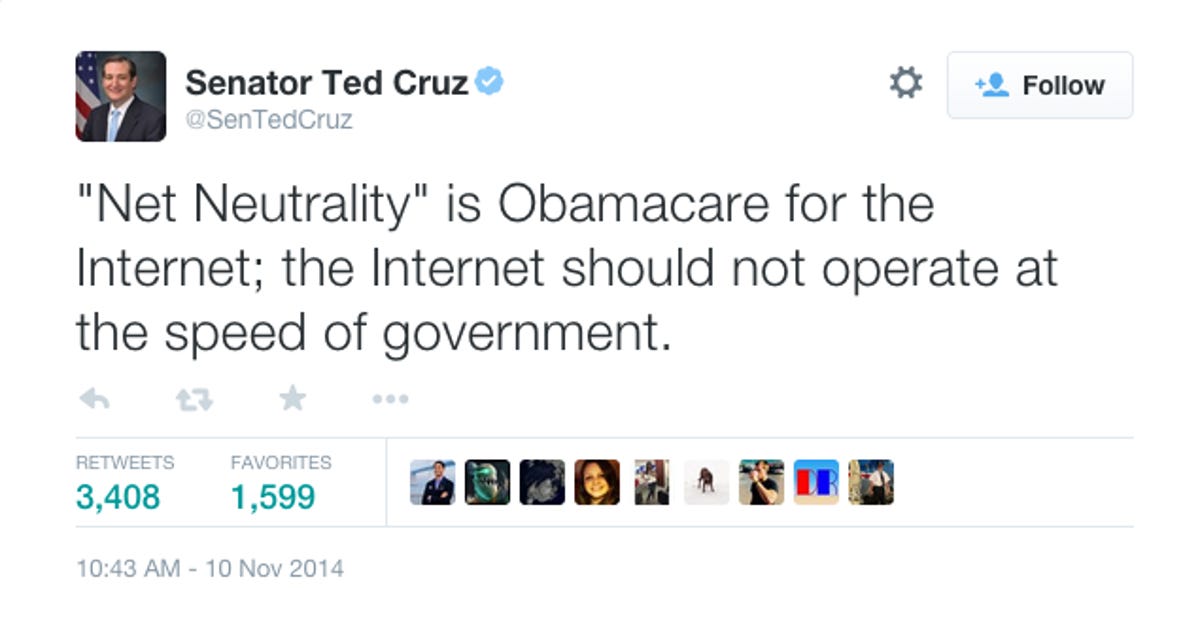

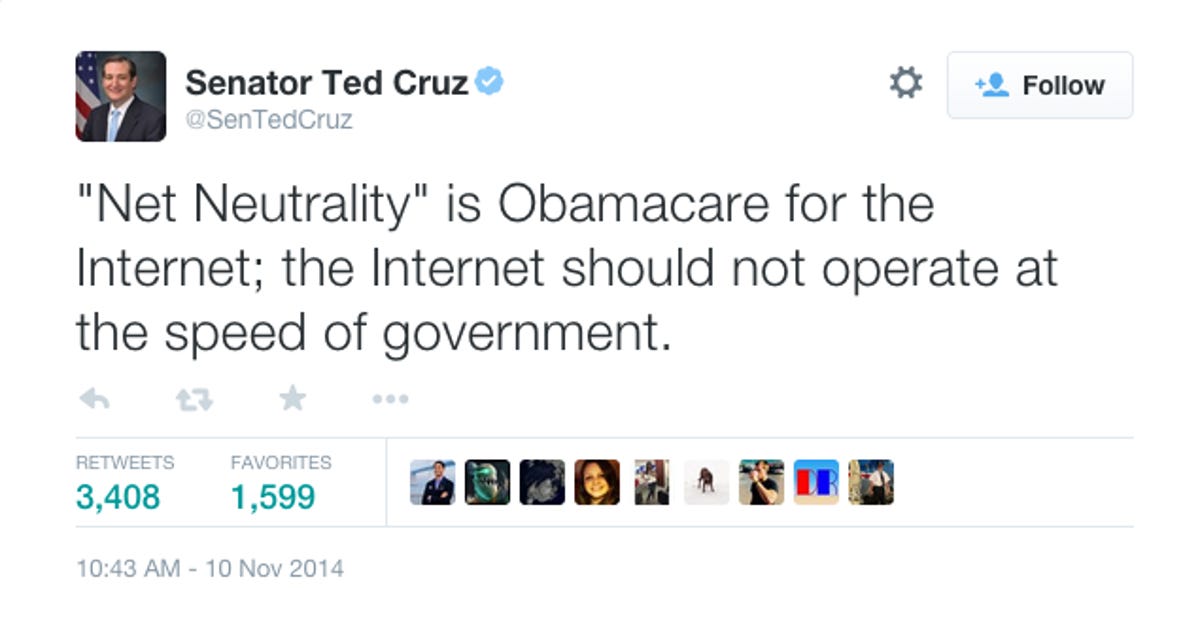

The debate over Net neutrality, and more specifically the fight to reclassify broadband as Title II service, has turned into another bitter partisan battle in Washington. Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) called the new regulation “Obamacare for the Internet.”

Republicans have also accused the White House of skewing the independence of the FCC, with some seeking an investigation into Obama’s role in shaping the rules, since Wheeler’s initial proposal, made public in May, did not include reclassifying broadband traffic.

After a public outcry, including a 13-minute rant by HBO comedian John Oliver who implored viewers to flood the FCC with comments, Wheeler said he changed his mind and became convinced the only way to protect the open Internet was to change the definition of broadband.

But Republicans say Wheeler was likely influenced by a statement issued by Obama in November that urged the FCC to reclassify broadband. Obama said in a nearly 1,100-word statement that there should be no toll takers between you and your Internet content, and he said Title II was the only way to ensure the Internet remained open to everyone.

Republican Commissioner Ajit Pai highlighted the change in position in his statement during the FCC’s meeting Thursday, asking why Wheeler changed his mind.

“Is it because we now have evidence that the Internet is broken?” he said. ” No. We are flip-flopping for one reason and one reason alone. President Obama told us to do so.”

Republicans in Congress have also drafted legislation that would write the Net neutrality rules into law but strip the FCC of its authority. But even though the Republicans control both the House and the Senate, they don’t have the votes to override an executive veto from Obama. As a result, the party’s leadership conceded earlier this week that it could not pass a Net neutrality bill without support from Democrats.

The fight continues

The vote today ends the most recent chapter of the Net neutrality battle, but it’s by no means the end of the story.

After the rules are published in the Federal Register, likely within the next few weeks, broadband providers are sure to file suit against the FCC. AT&T has already suggested it will sue. And it’s likely that other broadband providers will join the company.

FCC officials have said they anticipated such challenges, and they’re confident the rules will stand up to legal changes.

This story is part of a CNET special report looking at the challenges of Net neutrality, and what rules — if any — are needed to fuel innovation and protect US consumers.