On the 21st floor of New York’s Woolworth Building, the tallest building in the world when it was completed in 1913, there’s a new structure that’s on track to break records.

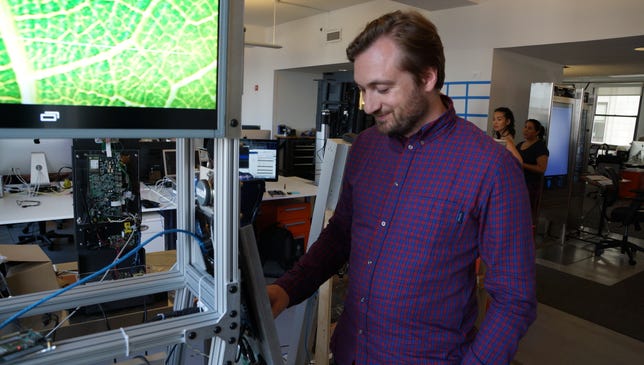

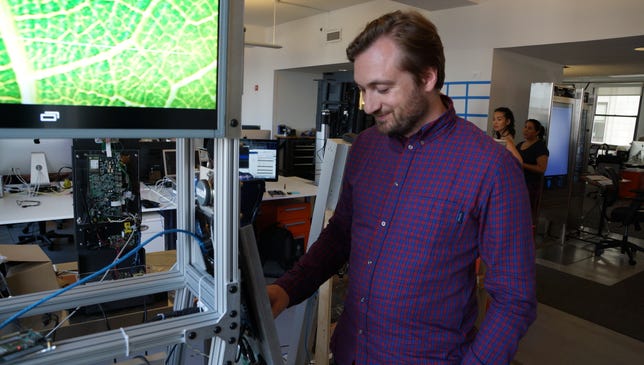

David Etherington, the chief strategy officer at municipal advertising giant Titan, is helping to create a structure that will supply free, ultra-high-speed Wi-Fi Internet to anyone within about 150 feet. Once completed, there will be up to 10,000 of these structures, known as Links, that will replace all of the city’s unused phone booths scattered across the five boroughs.

The new Wi-Fi hubs represent a push among city officials to elevate New York as a technology and innovation destination, a description that is most often resigned to Silicon Valley in the US and to many other cities abroad, namely London, Singapore and Seoul, where broadband is one-tenth the price it is in New York and twice as fast, according to the Open Technology Institute. And it underscores an effort to narrow the digital divide in New York with free, public high-speed Internet — a resource that President Barack Obama has called a 21st century necessity.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImagePaula Vasan/CNET

The project is the result of a $200 million plan approved by city leaders in December 2014, called LinkNYC. A consortium called CityBridge won the bid to remove old payphones and install new Internet infrastructure in their place. The group includes mobile chipmaker Qualcomm, which has helped with connection technology, and outdoor advertiser Titan, which already has the largest contract in the city for maintaining and advertising on city payphones. Comark, which will fabricate the actual kiosks, and strategy firm Control Group are also part of the consortium. The plan with LinkNYC is for the initiative to be not only self-sustaining, but hugely profitable with an anticipated half a billion dollars in ad revenue to New York over the next 12 years — money that will be used by the city for Internet connectivity-related projects.

The first 500 Link structures will be available by summer 2016, with the construction of the first 7,500 Links expected to go on for four years. The contract — exclusively for providing the Internet service and maintaining the Link structures — will last for up to 15 years. As planned, it would be the largest and fastest free public Wi-Fi network in the world, providing a cloud of gigabit-speed Wi-Fi access, and it would be the largest deployment of digital displays globally.

“These really are going to look amazing and they’re going to change the streetscape of New York,” Etherington said while pointing to an early prototype of the new phone installation, which looks like a mini modern skyscraper itself: a thin, sleek, 9.5-foot-tall hub providing unlimited Internet access at up to one gigabit per second, or roughly 100 times the average speed of public Wi-Fi. To put that into perspective for a busy New Yorker, those speeds allow you to download a two-hour high-definition movie in about 30 seconds. Each Link also comes with two USB outlets, letting you charge your phone by 10 percent in less than two minutes (but you have to bring your own cable).

What free Internet means for the Big Apple

Each Link structure will be able to serve just under 500 people with Wi-Fi at any one time, according to Etherington

“It will start to change people’s expectations around Wi-Fi if you can pop out for a pint of milk and download the Hobbit trilogy in a minute…it’s probably going to change your perceptions about what Wi-Fi is all about,” he said, before rattling off an alarming stat about Internet usage in the city: a total of 3.5 million people don’t have access to broadband Internet.

LinkNYC to bring free, public Wi-Fi to New York (pictures)

What if you luckily happen to live or work next to these structures? It could theoretically mean free Internet for thousands of New Yorkers who happen to live on the first and second floors of a building near a Link. Small businesses, too, may particularly benefit from free Internet, according to city officials.

The potential to lower that 3.5 million figure to zero, in terms of the number of people who lack Internet access, speaks volumes about opportunities in closing the digital divide.

According to the city’s Center for Economic Opportunity, 45.1 percent of New Yorkers live in households earning less than 150 percent of the poverty line, which, for a family of two adults and two children, is just over $31,000 in New York. “This divide is a big issue in our modern age,” said Minerva Tantoco, chief technology officer of New York City — a native New Yorker who witnessed that divide in various forms throughout her public school upbringing, surrounded by classmates on opposite ends of the city’s wide socioeconomic spectrum.

You need Internet access to participate in the modern economy, because “people who don’t have it are shut out,” she said on a call from outside Bronx High School of Science (her alma mater), where she had just finished serving as a judge for a student hardware competition.

Tantoco, who was appointed by New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio to the newly created chief technology officer position in September 2014 with the mission of making “the most technology-friendly and innovation-driven city in the world,” has been a key player in getting LinkNYC off the ground. Her mission in achieving free Internet can be summed up in a single sentence: Create a more equitable playing field through technology for everyone living in and visiting New York.

The goal: innovation and social equality

With ad revenue funding the entire LinkNYC initiative over the next 12 years, the city hopes that the digital advertising on the structures themselves will help spur innovation and social equity. At the start of the project, there will be six advertisers over four weeks, but after a few months when data on usage is collected, Etherington said companies will eventually be able to conduct smaller, more targeted ad buys for a lower price tag. It’s a setup that’s a result of a public-private partnership between the city and private businesses, which Etherington calls a strategy unlike any other municipality’s trying to offer free public Internet.

Advertisers will eventually be able to buy ads on Links, which each have a 55-inch digital screen, in specific neighborhoods, on specific streets, at specific times, rather than having to advertise on the entire network throughout the five boroughs.

More Road Trip 2015

- New York’s tech scene: More melting pot, less Silicon Valley

- Take a look at New York’s quietly vibrant tech scene (pictures)

- For a moment, Times Square plays art gallery

- The Midnight Moment in Times Square (pictures)

City officials say that the link structures will pay for themselves, not only because they will be self-sustaining from a business sense, but because it will spur a more informed community. “If you don’t have water or electricity you’re going to be at a huge disadvantage and it’s the same with the Internet,” Tantoco said.

Of course these structures aren’t intended to be a panacea for Wi-Fi in New York. But it’s certainly a first step…a leap actually…to turn New York into a smarter city.

While millions of people still lack Internet access, particularly in poorer neighborhoods, the people behind LinkNYC say the payphone upgrade represents the city’s commitment to eradicating the digital divide. The long-term goal, one championed by de Blasio, is for every resident and business to have access to affordable, reliable, high-speed broadband service by 2025. “Stories of kids sitting on library stoops late at night struggling to get homework done with spotty Wi-Fi is an example of what the digital divide can do, and a problem LinkNYC aims to solve,” said Etherington.

But what about privacy?

Tantoco and her team helped craft the privacy policy associated with the Wi-Fi hotspots, enforcing end-to-end encryption — which scrambles information so only the sender and intended receiver, and no one in between, can read it — using technology called “Hotspot 2.0.” That also let’s LinkNYC authenticate users once and allow them to roam from one Link to the next without re-authenticating each time.

What does that mean for you? To join the LinkNYC network you’ll need to give up your email address and username and create a password. So the network will know a fraction of what your home Internet provider or wireless carrier knows.

“In addition to privacy protections, LinkNYC will also be among the most secure Wi-Fi networks available,” said Nicholas Sbordone, a spokesman for New York City’s Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. “It will be one of the first public encrypted networks — so the act of listening to unencrypted wireless traffic will be eliminated.”

To prevent one device from being able to see any other device, the network will block peer-to-peer communication once a device is on the network. Therefore, a wireless device will only be able to access the Internet as opposed to other users’ devices, which will prevent the spread of viruses from one computer to another and stop a hacker from being able to attack another computer or device on the network, said Sbordone.

“If you go on a regular free Wi-Fi hotspot today like at the Hong Kong airport, it’s not encrypted and the data that you send can be reused for other purposes,” Tantoco said. “We wanted New York City’s policy for Wi-Fi to be much stronger than that.”

“I used to work in the financial sector, where security has always been the No. 1 consideration, and I’m applying that to government,” she adds, noting her experience in technology and product management positions at companies like UBS and Merrill Lynch.

That level of end-to-end encryption for LinkNYC is a new frontier of free public Wi-Fi. In fact, according to Etherington, LinkNYC will be the only free public Wi-Fi in the world to have and mandate that level of end-to-end encryption throughout the network.

Still, the familiar objection to public Wi-Fi largely centers on the ability among hackers to defeat security and encryption settings, security experts say. “Expanded Wi-Fi connectivity will have a tremendous benefit, but as we have seen in recent months, such as with the hacking of devices, increased connectivity comes with an increased opportunity for cyberattacks and malicious activity, even if there is end- to-end encryption,” said privacy and cybersecurity lawyer Stuart Levi.

Etherington acknowledges the validity of these critics. “When it does go wrong it can really go wrong. But we don’t have that level of information in the first place,” Etherington said of LinkNYC’s encryption policy, which Tantoco said will discourage hackers from hanging around LinkNYC sites in the first place. If you want to use the Wi-Fi from LinkNYC, all you’ll need is your name and your email address. And once you log in once, you won’t have to ever again, whether you’re using LinkNYC Wi-Fi in Manhattan or Staten Island.

Steve Koonin, founding director of New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress, said the benefits of free public Internet in New York City outweigh the privacy concerns associated with it. “I think those concerns are just becoming a fact of modern life,” he said, equating the trade-off of information in exchange for a service to giving up his financial information to his credit card company in exchange for fraud protection alerts.

With free Internet, NYC is far from the first

The arrival of LinkNYC comes despite a turbulent history of municipal Wi-Fi projects, with cities including New York, Philadelphia and dozens others throughout the US trying — and failing — to develop such technology and keep it running. In 2004, for example, San Francisco’s Mayor Gavin Newsom declared: “We will not stop until every San Franciscan has access to free wireless-internet service.” But stopping proved inevitable, as the project turned out to be harder than expected. And now, more than 10 years later, a sliver of Newsom’s vision is becoming a reality, with Google covering 33 of the city’s 220 parks with Wi-Fi. Officials say the Wi-Fi speed is lower than gigabit speed, with endpoint-to-endpoint encryption an option only at one location as opposed to being enforced throughout the network.

In April 2014, Boston started providing free public Wi-Fi in public spaces, targeting an area that consists largely of low-income families who may not be able to afford the high cost of speedy broadband service. There are now 180 hotspots, often lower than gigabit speed. Similar to San Francisco’s policy, end-to-end encryption is an option as opposed to being enforced.

Cities from San Francisco and Seattle to Boston and New York have claimed these kinds of projects can help ignite economic activity and innovation, narrowing the digital divide between those who can afford to access the Internet and those who can’t. But despite the progress in US cities, many of these projects have been curtailed after cities and developers encountered financial, competitive and technical obstacles.

“It’s an opportunity for New York to leapfrog places like Tokyo and Seoul and become the connectivity heart of the world,” Etherington said of LinkNYC.