CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Joe Paradiso chuckles at the unexpected growl of a small aircraft engine.

The airplane isn’t overhead. It’s 50 miles away, passing over a former cranberry bog that Paradiso and his research team are monitoring. Microphones planted there have relayed the sound to his workspace here at the MIT Media Lab as we look at a computer screen showing the virtual Tidmarsh landscape.

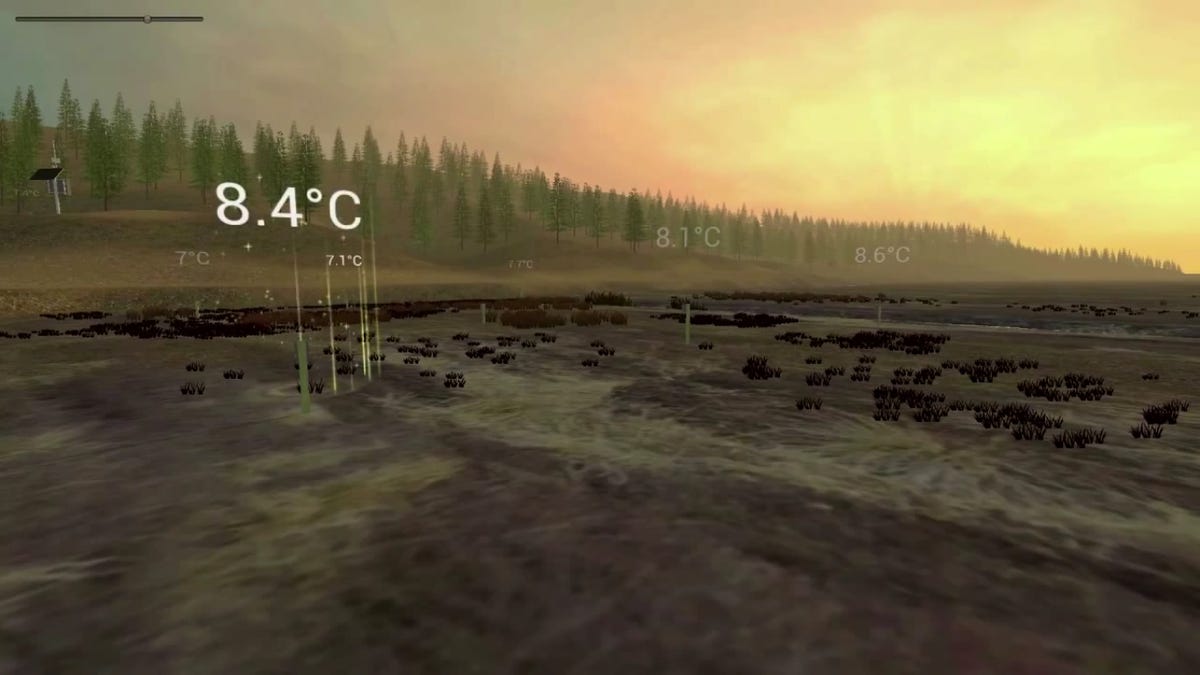

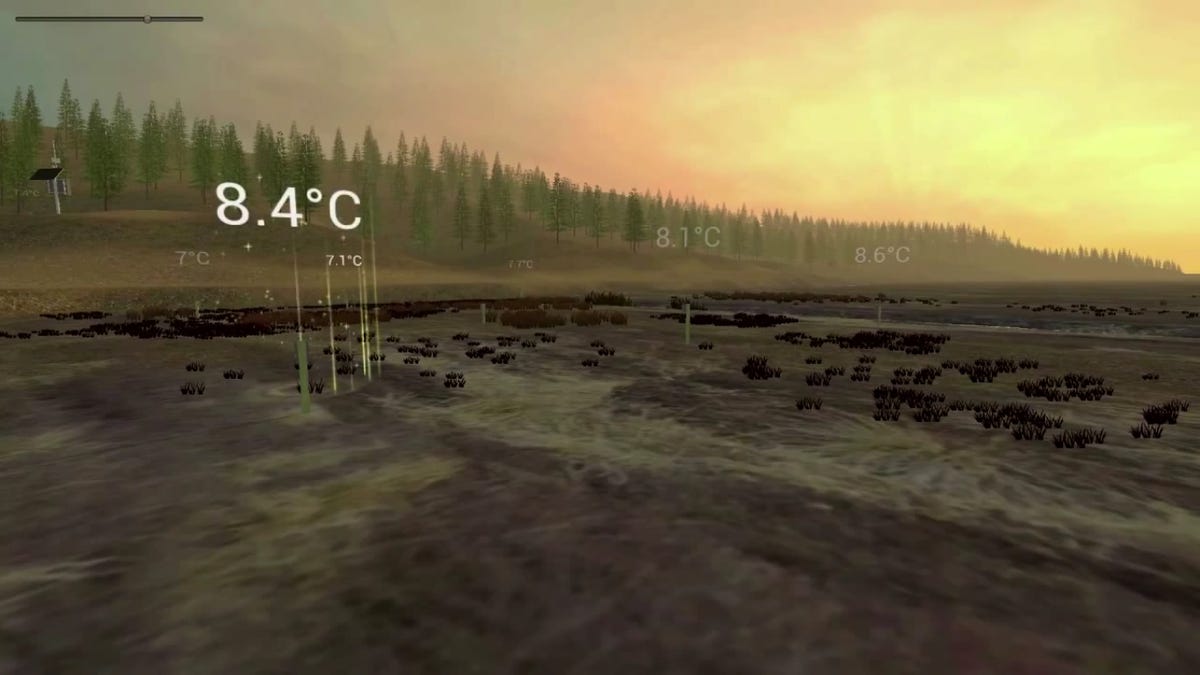

The laser-scanned view of the wetland shows temperatures logged by dozens of sensors carefully placed in the 600-acre expanse. We’ll soon be able to see numbers for humidity, light level and other climate stats.

The airplane quickly passes, and we can better hear the atmospheric, New Age-y soundtrack shaped by the stream of data. Paradiso, 59, calls to a colleague to see about switching to a spookier nighttime sound.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge Image“The future comes fast,” says Joe Paradiso at the MIT Media Lab.

Jon Skillings/CNET

It feels rather like a video game, and that’s by design for Paradiso and his Responsive Environments group.

“One thing we like to do…is create new experiences,” said Paradiso. “Our theme is really about sensing, as in the nervous system of the planet.”

Paradiso’s reimagining of farmland is only one of the far-out projects at the Media Lab, a six-story future factory located a block from the Charles River on the eastern fringe of the MIT campus. The Media Lab, which prizes an “antidisciplinary” and hands-on academic culture, celebrates its 30th anniversary Friday.

You’d frustrate yourself trying to categorize the work being done here. The names of the two dozen research groups are wildly diverse and evocative: Opera of the Future, Lifelong Kindergarten, Synthetic Neurobiology. More than 150 graduate students, 40 faculty members and a steady stream of visiting scientists and undergrads pitch in on the 350 projects currently under way.

Nothing is out of bounds for the Media Lab. Peer through the floor-to-ceiling glass walls of the building’s labs and you’ll find researchers building prosthetics, personal robots, holographic video displays and glass objects created by 3D printers.

‘Do interesting things’

That diversity and openness are part of what keep the ideas sparking.

“It’s really a synthesis between art, science, engineering and design,” said Joi Ito, director of the Media Lab. “Having all of this happening in the same place allows you to do things and impact the world in an interesting way.”

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageFor Joi Ito, director of the MIT Media Lab, the goal is to achieve “a synthesis between art, science, engineering and design.”

Jon Skillings/CNET

The creative mishmash serves to do more than generate pie-in-the-sky ideas. It attracts corporate sponsors that provide the majority of the Media Lab’s close to $60 million annual operating budget. More than 80 companies — the Media Lab calls them “members” — pay the minimum $250,000 fee to belong to the club. Members, which make a three-year commitment, include Google, Intel, Twitter, Toyota, GlaxoSmithKline, Estee Lauder, Ikea, New Balance and Coca-Cola.

Corporate participation isn’t simply sponsorship of academia. The fee gives members royalty-free licensing for as long as they’re members. It’s an arrangement that has led to, among other things, Lego Mindstorms robot-building kits.

“That’s a really important design feature,” said Michael Horn, co-founder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, a think tank focused on innovation. “Otherwise it would create a closed community…and effectively create a customer relationship that would limit the collaboration that’s so important for the Lab to work well.”

The Tidmarsh Living Observatory serves up data from a former cranberry bog in a setting that resembles a video game.

MIT Media Lab

Startups and spinoffs

E-Ink Corp. may be the Media Lab’s biggest success story. Spun out in 1997, the company developed “electronic paper” displays, low-power screens that replicate book pages. If you own an Amazon Kindle or Sony e-reader, you’ve used E-Ink’s technology.

Other projects have also translated into commercial success. Spotify, the streaming music service, bought Media Lab progeny Echo Nest last year for an undisclosed amount. Echo Nest was coveted because its software tools help make sense of music-listening data for online radio services and social media outlets.

EyeNetra, based in neighboring Somerville, Massachusetts, spun out of the Media Lab’s Camera Culture group in October 2011. The 15-person startup designs simple, smartphone-powered eye tests that can be conducted outside of an optometrist’s office.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageRamesh Raskar of the MIT Media Lab shows off the Netra device.

John Werner/Camera Culture Group

Its product, the Netra, resembles a plastic binocular case. A Samsung Galaxy S4 smartphone snaps into the end of the case and you peer through the other. As you turn dials to respond to patterns on the screen, an app measures your degree of nearsightedness, farsightedness or astigmatism.

At $900, which includes the smartphone, the highly portable Netra is a fraction of the cost of standard diagnostic machines. Commercial sales of the device began in August, and it is already a key tool for the company’s Blink service, which launched in New York City to provide on-demand eye tests. It is also being used in the similar Nayantara service in India.

The technology could soon be used to develop prescription displays for virtual-reality headsets.

Not all of the Media Lab’s creations will have a quick payoff. A few years back, for instance, the Camera Culture group designed an array of 500 sensors and a titanium sapphire laser that captures 1 trillion frames per second. It has not had an immediate real-world application, but people at Media Lab say it could eventually prove useful in medical imaging, industrial design and even consumer photography.

“We try to capture the world in the most crazy, amazing way we can,” said Ramesh Raskar, an associate professor who heads the Camera Culture group. “Then [we] try to make sense of all of it in something that can be comprehended by everyone.”

Data from the wild

Camera Culture and Paradiso’s Responsive Environments group are both part of the Lab’s Center for Terrestrial Sensing, whose mission is to find new ways to “sense and visualize inaccessible natural environments.”

One of Responsive Environments’ core projects centers on the Tidmarsh Living Observatory, a pair of former cranberry farms near historic Plymouth, Massachusetts, that are being restored to their natural state as bogs.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageThe MIT Media Lab building is a commanding presence on a quiet street corner in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Jon Skillings/CNET

The bogs, a distinctive North American wetland environment, are dotted with an array of low-power sensors to measure temperature, humidity and light.

For Paradiso, the project is about more than recording climate statistics. It’s about what it means to be “present,” experiencing and understanding the world about you as fully as possible, with technology helping to make that happen.

The Tidmarsh initiative aims to let people interact with data in a 3D environment through a “cross-reality browser” built on the Unity game engine. The software crawls through sensor data the way search engines crawl through data on the Web. The long-term goal, in Paradiso’s view, is to liberate viewers from the laws of physics.

“They can float around. They can zoom up and down. They have access to information everywhere,” Paradiso says in a video about the project. “We took the sensor data as a canvas for being creative.”

Tidmarsh picks up from an earlier project that used sensors to keep tabs on the Media Lab building, and it offers a hint of how we might interact with the Internet of Things, shorthand for a connected world in which cars, homes, sidewalks and clothing monitor and tabulate our lives.

It’s also an example of the Media Lab’s overriding concept: no idea is too crazy. To borrow the title of Stewart Brand’s late-’80s book about the institution, everyone there is inventing the future. It’s all about looking beyond the horizon.

“The future comes fast,” said Paradiso.