Netflix

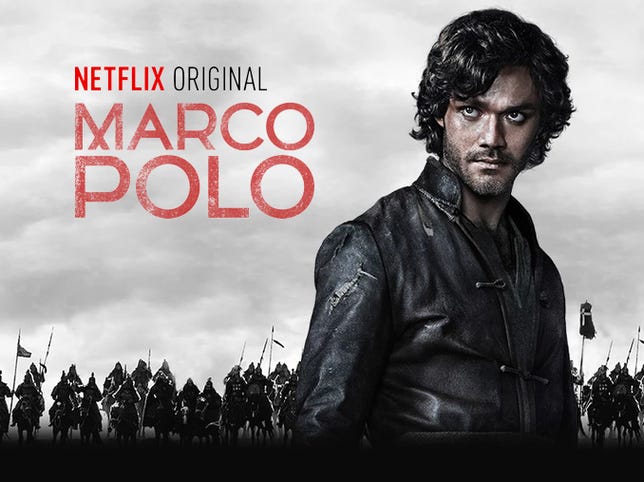

A senior figure at one of Europe’s biggest broadcasters has hit back at Netflix’s original programming as she insists viewers still want to watch TV the traditional way. “I don’t know if anybody is watching ‘Marco Polo’, do you?” asks Mai Fyfield, group director of strategy at BSkyB. “Nobody knows.”

Online film and TV streaming service Netflix claims the vast swathes of data it has collected on people’s viewing habits — what they watch, which actors they like, and what they turn off when they don’t like it — allows the service to make confident bets on original programmes.

Those bets have paid off with major successes such as “House of Cards” and “Orange is the New Black”. When actor Kevin Spacey and director David Fincher were frustrated that TV networks would only commit to a pilot episode of their risky new political drama “Cards”, Netflix stepped in and commissioned a full series. The result: a bag of awards nominations and the acknowledgement of Netflix as a major player in the TV world.

But Fyfield, of the UK’s biggest pay-TV broadcaster Sky, points out that Netflix refuses to reveal how many people actually watch its original programming, like the recent historical drama ” Marco Polo“. That said, some light has been shed on the subject by Luth Research, a company not affiliated with Netflix that tracks viewer behaviour across a sample of 2,500 Netflix subscribers. In results reported by entertainment bible Variety, superhero show “Daredevil” appears to have been an instant hit and “House of Cards” a continuing success, while “Marco Polo” and “Bloodline” haven’t found such substantial audiences.

Fyfield questions whether data is more useful than human involvement. “We have data coming out of our ears,” she says of Sky, “but we don’t use a lot of it.”

Netflix original shows of 2015 and beyond (pictures)

+47 more

Referring to viewers, Fyfield argues, “Nobody knows what they want until someone puts it in front of them. It’s more of an editorial and creative process.”

Netflix declined to comment.

Fyfield believes that Sky is putting its money where its mouth is in terms of premium quality television, with recent programmes like “Fortitude” and a co-production deal with US broadcaster HBO. “In order to get that first-run glossy content we had to make it ourselves, and we’re committed to spending £600 million a year doing just that.”

Sky

Fyfield appeared at the FT Digital Media conference in London Wednesday to discuss changes in the world of TV with Roku’s vice-president of content acquisition, Ed Lee; and venture capitalist and founder of video monetisation platform Blinkx, Suranga Chandratillake. They discussed the big trend in television in recent years, which is the same trend that’s happening across all media: the shift from traditional models to digital, online — and increasingly mobile — on-demand consumption. Whether it’s Spotify, Netflix or Scribd, we increasingly want our music, films and books when we want, how we want and on any device we want.

That could be bad for traditional linear broadcasters like Sky. “There is a shift going on — linear viewing is declining between 4 and 5 per cent per year and has been for a few years,” Fyfield admits. But she believes that watching TV shows on a TV will continue. “My personal view is that linear television will go on for some time…10 years after putting [digital recording system] Sky+ in people’s homes, 80 per cent of TV viewing is still live. I think in five or 10 years time around 50 per cent will still happen live. People like that lean-back, passive experience.”

TV reaches for the Sky

- At 25, is Sky a dishy delight or deep-pocketed menace?

- Sky and HBO teaming up to make next Sopranos or Game of Thrones

- Sky looks to the next generation of TV, backs Oculus Rift startup

Fyfield argues that experience gives the viewer more than consuming specific programmes, highlighting that Sky has invested in video startup Pluto.TV to continue what she calls the “serendipitous discovery” of stumbling onto something as you flip channels. “When you tune into BBC One on a Saturday night,” she says by way of example, “you know what type of programme you’re going to get. Viewers value that.”

But venture capitalist Suranga Chandratillake argues technology has made linear viewing redundant. “I think we watched linear TV because the technology forced us into it. There’s this voodoo that TV is social and we all watch it together — I don’t buy that. There are some causes for linear programming: [Manchester] United and City kick off at that time so you have to watch it then; and event programming will continue. But I think watching TV in a linear fashion is just a habit.”

He points out that people still watch and discuss TV shows, just in different ways. “I watch a lot of box sets and I still have water-cooler conversations about ‘Breaking Bad’, but not based on the fact that we all watched it at the same time.

“I challenge the magic idea of watching TV together. I think it will die.”

The future of TV

- ‘House of Cards’ producer predicts Silicon Valley will replace Hollywood

- Netflix invades Europe: Why expansion beyond the US is so critical

- Netflix signs up new members like crazy in record-breaking quarter

- ‘Daredevil’ gets a second season on Netflix

- Amazon snags Woody Allen to write and direct his first-ever TV series

But Chandratillake does concede that the new players still need to learn lessons from the old ways. “The things that linear TV has cracked will have to be re-cracked in the online world,” he said.

Fyfield brings the conversation back down to earth by pointing out aspects of the technology still have a way to go anyway. Sky has moved with the times to deliver the Sky Go catch-up and on-demand service for people who have a Sky dish, and Now TV, a similar service for non-subscribers , but it’s one thing to have services offering a choice of things to watch and quite another to deliver to vast numbers of people.

“It’s hard streaming a Premier League game to 4,000,000 viewers at the same time,” Fyfield said. “The infrastructure isn’t there yet to stream to millions of people who want to watch the same programme at the same time.” Just ask anyone who tried to watch the premiere of “Game of Thrones” online last year, which crashed both Sky and HBO’s online services for UK and US viewers.

28 new TV shows to geek out over in 2015 (pictures)

+25 more

Chandratillake believes that improvements in infrastructure involve “more than putting in new wires” and foresees change from “big leaps [like] machine-learning in video compression, and peer-to-peer localised streaming so your neighbours help you watch a football match.”

For the moment, innovations in quality are outpacing infrastructure. “If viewers are watching things in HD, 4K, HDR, there’s a question over whether the infrastructure can handle it,” says Fyfield, “certainly in the next five years.”

In the meantime, however, “Viewers don’t care about content quality as much as you’d think,” according to Chandratillake. “People watch video on their phone that isn’t HD but they care more about being able to watch what you want where you want it. We all do it when we pick up a Kindle — it’s not as nice as reading a book, but it’s more convenient.”

Fyfield believes that in all this talk of new technology — like a Roku set-top box or Apple TV — and new content services — like Netflix — one thing that’s often overlooked is “the power of being able to sell.” She believes that “people in the States who are going direct to consumers may find it harder than they thought.”

Or as says Chandratillake puts it, “Content creation is weird, complex and fragmented; content consumption is weird, complex and fragmented. So there will always be middlemen.”

Now playing:

Watch this:

Everything you need to know about Netflix Originals

1:50