Forget about fast lanes. The new buzzphrase in the battle for an open Internet is “zero rating.”

Enlarge Image

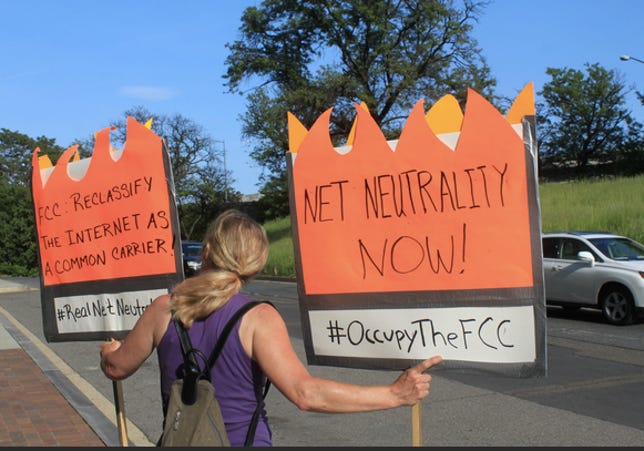

Enlarge ImageThe battle over the FCC’s Net neutrality rules is far from over.

Kevin Huang/Fight for the Future

Zero rating is the practice of giving you online services, like music and video access, that don’t eat into your data allotment. T-Mobile’s Binge On service, which gives you unlimited video streaming from certain services, is a prime example.

Not surprisingly, consumers love the option. But opponents say it’s a sly attempt to stifle competition because it favors services from specific companies.

Now the issue threatens to reignite the debate over Net neutrality, one year after the Federal Communications Commission passed rules that guarantee carriers and other providers treat all Internet traffic the same.

“It’s just another form of favoring one application over another,” said Barbara van Schewick, a Stanford law professor. In January, she published a report accusing T-Mobile’s Binge On service of violating Net neutrality.

Zero rating has already become a point of contention worldwide. Regulators in India earlier this month rejected Facebook’s Free Basics service, which gives customers free access to hand-picked services. In the US, AT&T’s Sponsored Data and Verizon’s FreeBee charge business customers a fee so consumers don’t have to worry about data caps when they watch content from those businesses. Comcast subscribers can stream as much video as they want through its own Stream TV service without it counting against their data caps, putting streaming services like Hulu at a disadvantage.

If you’re not convinced that this practice is a bad thing, you’re not alone. The FCC is still mulling it over. The agency’s Net neutrality rules don’t ban such deals but do allow it to review complaints. Late last year, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler said he would keep an eye on T-Mobile’s Binge On service while also praising the service for its innovation. The agency has asked T-Mobile and others for more information about their plans, potentially signaling its intention to take action.

All of this is happening as a federal court deliberates whether the FCC’s Net neutrality rules adopted one year ago today are legal. AT&T, along with cable and wireless industry associations, are suing the FCC over the rules.

Figuring it out

Many experts agree that the zero-rating services in the US don’t violate the FCC’s three major rules, which prohibit carriers from blocking services, slowing traffic or forcing businesses such as Netflix to pay for faster delivery of their services.

More on Net neutrality

- Net neutrality turns 1: Here’s everything you need to know (FAQ)

- FCC chief on solving the Open Internet puzzle (Q&A)

- T-Mobile CEO: Binge On is ‘completely compliant’ with Net neutrality

- How the mission for Internet equality is playing out around the world

The FCC also included a much broader “general conduct standard.” This allows the FCC to decide on a case-by-case basis if a provider is “unreasonably interfering” with consumers’ access to content.

Broadband providers say they aren’t trying to pick winners and losers on the Internet. They see no harm to consumers when someone else picks up the tab for the data service they’re using.

“Today the full cost of delivering data is borne by the consumer,” said David Young, vice president of public policy for Verizon. “Why not allow for some experimentation?” He compared Verizon’s FreeBee program to toll-free long-distance calling, where marketers pay for consumers’ calls.

T-Mobile’s Binge On service helps the carrier stand out, said Kathleen Ham, the company’s senior vice president of government affairs.

“This is a very competitive market,” she said, suggesting the FCC should “tread lightly” in its interpretation. “We have to make sure the customer has choices.”

A little drama

So far, T-Mobile has felt most of the zero-rating heat. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights advocate, got into a public spat last month on Twitter with T-Mobile CEO John Legere after the group said the service violates Net neutrality by forcing all video, not just those participating in Binge On, to be streamed to devices using a lower resolution, which uses fewer network resources. Legere, who admitted the company compresses video when Binge On is active, later apologized for a clip he posted on Twitter in which he went on a 24-second rant that asked “Who the f— are you, anyway EFF? Why are you stirring up so much trouble and who pays you?”

T-Mobile counters that its service is open to all video providers, and customers can turn off the service at any time.

“I maintain my belief that Binge On will be one of the biggest things that we’ve ever done as a company,” Legere said during the company’s fourth-quarter earnings call last week.

T-Mobile said that in the first three months of Binge On’s launch, customers had more than doubled the number of hours they spent watching video each day. One major video service on Binge On, which T-Mobile didn’t name, saw a 79 percent jump in daily viewers. Even video services that aren’t included in Binge On say they’re seeing an increase in viewership by at least a third, according to T-Mobile.

What about your data cap?

Still, critics say zero-rating simply highlights the arbitrary nature of Internet providers’ data caps. Matt Wood, policy director for Net neutrality supporter Free Press, argues that if operators can exempt an entire class of service, like video, or allow unlimited access to certain applications, then data caps designed to rein in network hogs aren’t really necessary.

His point: Artificially low caps on data can make zero-rating services look more attractive than they actually are.

“It’s like getting $1,000 off on a car you bought when the price was inflated by $5,000,” he said. “Is that really a good deal?”