Voice-activated digital assistants like Google Assistant and Amazon Alexa make trivial tasks like playing your favorite song as simple as saying a few words. But for people like Giovanni Caggioni, who has Down syndrome and congenital cataracts, which makes him blind and unable to speak, these tools are inaccessible without some of sort of augmented hack.

Caggioni, 21, loves music and movies. But he can’t use the family’s Google Home device or the Google Assistant on his Android phone himself because he can’t give the “OK Google” command to search for his favorite entertainment.

His older brother Lorenzo, a strategic cloud engineer at Google based in Italy, set out to solve this problem. In an effort to give his brother greater independence, Lorenzo and some colleagues in the Milan Google office set up Project Diva to create a device that would trigger commands to the Google Assistant without using his voice. It involves a button that plugs into a phone, laptop or tablet using a wired headphone jack that can then be connected via Bluetooth to access a Google Home device.

Lorenzo knew that with the proper technology adaptation, he could make Google Home a useful tool for Giovanni.

“When he is supported by people who believe in him,” Lorenzo said in an interview with CNET, “and when he has the right setup, the right tools, the right environment around him, he is really able to exceed any expectation.”

Project Diva is one of three new projects that Google highlighted at last week’s Google I/O conference, ahead of Global Accessibility Awareness Day. The company has been working on accessibility issues for several years to try to ensure its products are more accessible. For instance, the Google Maps team launched a program to use local guides who scout out places with ramps and entrances for people in wheelchairs. Last year, at the I/O developer conference, Google announced the Android Lookout app, which helps the visually impaired by giving spoken clues about the objects, text and people around them.

Google’s effort is part of a broader trend among big tech companies to make their products and services more accessible to people with disabilities. Digital assistants, in particular, have been the focus of several efforts already. Last year, Amazon made the “Tap Alexa” feature available for the Echo Show touchscreen smart speaker to allow deaf users to tap on the screen to access customizable shortcuts to common Alexa tricks, including weather, news headlines and timers. It also offers Alexa Captioning, which allows users to read Alexa’s responses.

“The more access methods, the better,” said Jennifer Edge-Savage, an assistive technology consultant in Massachusetts. “There are lots of mainstream technologies that can make life so much easier for people with disabilities. So something that’s just cool for me could be life-changing for the people I work with every day to help them to be more independent.”

Adapting technology

For Lorenzo, adapting Google Assistant for Giovanni was personal. Lorenzo said that Giovanni, the youngest of six siblings, was the brother who “completed our family.”

“He has always given so much to our family, I wanted to give back something to him,” he said. “I like technology. So that was something I could do for him.”

Lorenzo said he was inspired by the approach his mother took while raising Giovanni.

“My mom always made sure that Giovanni had access to all the same gadgets and technology that everyone in the family and all his friends were using to listen to music or to enjoy cartoons,” Lorenzo said.

There were several challenges to consider in designing a tool for Giovanni to use. Giovanni is severely limited in his communication. Not only does he not speak, but he only knows a few basic signs in sign language.

Because of limitations in fine motor skills, he’s also unable to manipulate a smartphone or tablet. And due to his cognitive disability, Lorenzo said that Giovanni is unable to navigate a complicated user interface with multiple steps or prompts.

Lorenzo is working to make Google Assistant more accessible for his brother, Giovanni, who has Down syndrome, is blind, and doesn’t speak.

Giovanni has recently been working with therapists to learn how to use a communication device with big buttons that connect to a device and play a prerecorded voice response. These buttons, which use the standard Augmentative and Alternative Communication framework, or an alternative way of communicating to replace speech and written text, attach to a device and can work as an on/off switch or can be chained together to handle more complex requests.

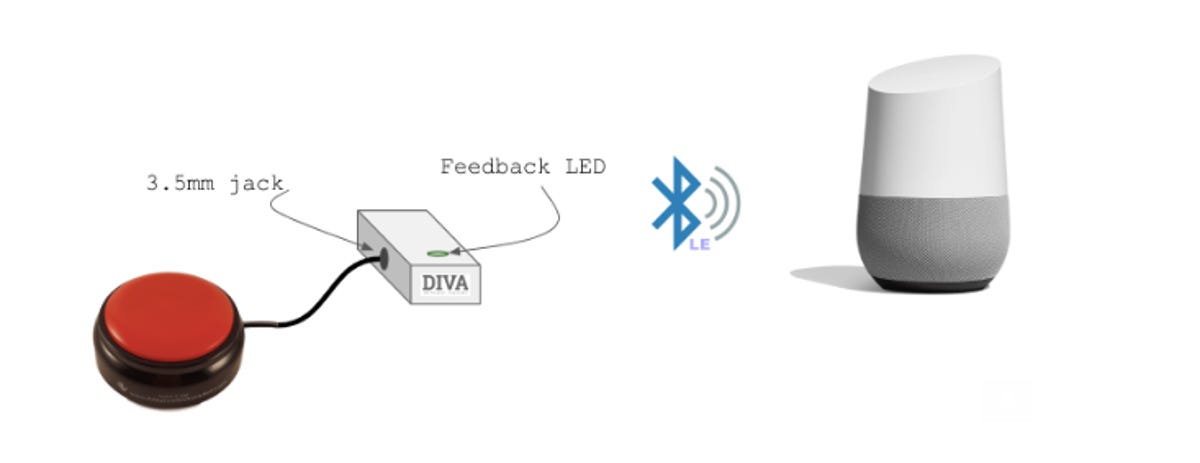

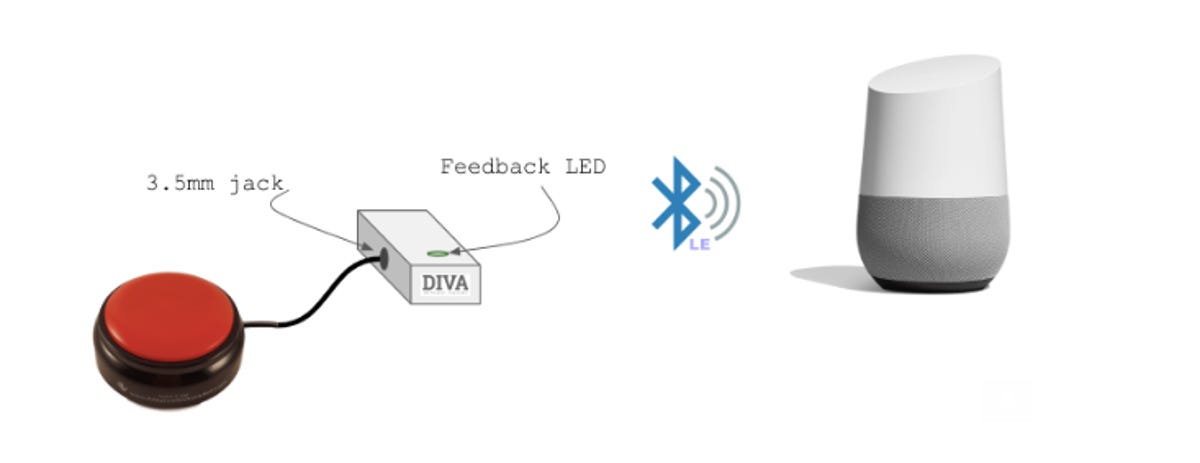

Lorenzo decided to create a gateway device that would allow Giovanni to use these buttons, which he’s already familiar with, to access Google Home. The team created a small box connected to a button using the same headphone jack used for a phone, laptop or tablet, using a wired headphone jack, that is then connected via Bluetooth to access a Google Home device. Now, by simply touching a button, Giovanni can listen to music or watch a movie.

Edge-Savage said many people who are unable to speak are already using AAC devices to press a button or an icon on a tablet or some other specially designed device to play preprogrammed voice commands for digital assistants. But Lorenzo’s solution bypasses the need for separate devices to generate a voice command. For people like Giovanni, who are just learning to use an AAC device, this could be a helpful tool.

“To me this is magic,” Edge-Savage said. “Here’s a brother who said, I am going to make something so you can do your favorite thing. That’s often where I start with clients as they learn how to communicate. It’s so motivating.”

Now playing:

Watch this:

The battle for the best smart display: Google Home Hub…

4:05

The way kids interact

Right now, Giovanni is using a single button, and the content is already queued up for him. But eventually the system could be expanded to let him choose from a variety of content and may even allow for more searching capabilities. Lorenzo said his team has plans to attach RFID tags that could be coupled with pictures with different information queued up.

“You could have these buttons all over the house,” Lorenzo said. He describes the system as a sort of jukebox, with buttons set up to tell him the weather, give him the news or tell a joke.

Even in the current setup, Lorenzo says it’s been a game changer for Giovanni. On a recent visit to his parents’ house, Giovanni was watching TV with Lorenzo’s young children. Apparently, Giovanni didn’t like what they were watching, so he went over to the TV, pressed the button and switched to Finding Nemo, his favorite movie.

“In this way, Giovanni is able to compete with my kids,” Lorenzo said. “This is the way my kids interact with each other; whoever controls the remote control decides what they watch. And now Giovanni is able to join them and has control, too.”

This drawing illustrates how the technology created in Project Diva can be used to provide alternative inputs to a device powered by the voice-activated Google Assistant.

While this task of simply changing the TV may seem insignificant, Angela Standridge, a speech-language pathologist, who specializes in the use of augmentative communication technology, said even this basic form of communication is significant for someone like Giovanni who has limited communication.

“The most powerful thing I do in my practice is teach people to communicate ‘stop’ or ‘don’t,'” she said. “The whole reason to communicate is to control your environment. Having that sense of agency and control is fundamental to us as humans.”

Making tech accessible

Assistants like Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant can be a lifeline for certain communities like the blind or visually impaired, or those with physical disabilities, but the need for voice commands leaves out a slew of other people.

It would be better for companies to think of these populations as they design their products, so that they can be accessible to as many people as possible, Edge-Savage said, adding that there are many ways to hack mainstream technology to make it accessible. Lorenzo’s system is a good example of such a hack — even if it was done in house.

Google is also using machine learning as part of another initiative, Project Euphonia, to make it easier for people with slurred or hard-to-understand speech to use Google Assistant.

“Building for everyone means ensuring that everyone can access our products,” Google CEO Sundar Pichai said on stage at Google I/O. “We believe technology can help us be more inclusive, and AI is providing us with new tools to dramatically improve the experience for people with disabilities.”

But some experts say that big tech companies could be doing more. Standridge said Google and other big companies need to think about people with disabilities when they first design these products.

“Accessibility is still an afterthought for all the big tech companies,” she said. “They’re retrofitted for people with disabilities. If they used universal design when coming up with their products, they would have a tool that could be accessed by the widest range of abilities from the start.”