FCC

The Federal Communications Commission has inched closer to a new policy that will allow the federal government to share wireless spectrum with various companies. The result: more room on the airwaves for our cat videos.

The FCC voted unanimously Friday to approve a new set of policies that will allow the federal government to share spectrum in a section of the airwaves known as the 3.5 GHz band, which has historically been used by the US military for radar. The new spectrum policy will allocate specific exclusion zones in areas where the government is using radar on this spectrum.

For the rest of the country, the FCC will auction off “priority” licenses in small geographic areas to wireless operators or other companies. These licenses will only be in place for three years. This is in contrast to traditional spectrum licenses, which cover an area that is at least 100 times larger and will last forever. The “priority” licensees will also be sharing spectrum with unlicensed users. Spectrum-sensing technology and a database of priority license users will minimize interference among spectrum users.

All the details for the new approach have not been worked out yet in this “experiment” to free up spectrum, the FCC says. But the agency is confident it will find a useful solution, both through new technology to manage wireless signals, public comments on its new wireless rules and additional work with private industry players like AT&T and Verizon, the biggest carriers in the US.

The goal of this change in spectrum ownership policy is to help free up public airwaves more quickly to fuel consumer demand for mobile data services. Wireless data usage is growing so rapidly, companies say they need ever more spectrum to keep up. Wireless data doubled between 2012 and 2013 and it’s expected to grow 650 percent by 2018, according to forecasts from equipment maker Cisco Systems.

The move is a major shift in how the government has allocated wireless spectrum for more than 100 years. Since the Radio Act of 1912 passed by Congress in the wake of the sinking of the Titanic, the government has sliced and diced wireless spectrum into discrete exclusive licenses to prevent interference among users.

The government has regulated wireless spectrum for the past century in efforts to ensure compatibility among various devices and to avoid interference.

But the FCC has had a difficult time keeping up with demand for more licenses as demand for more spectrum has risen, particularly among smartphone users who are increasingly tweeting, sending Instagrams and streaming video. In the 2010 National Broadband Report, the FCC recommended a plan to free up some airwaves over a ten year period. Since that time, President Obama asked his President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, known as PCAST, to look for new and innovative solutions to make more spectrum available to the public.

In addition to making spectrum available more quickly by allowing commercial users to share the spectrum with government users, the proposal will also create licenses for smaller sections of the airwaves, and for shorter amounts of time. A typical license, for example, is perpetual, while these new ones would expire after three years. This could help wireless carriers temporarily bolster capacity in high-demand areas like stadiums, college campuses, or airports.

The plan could also offer smaller companies an opportunity to purchase these smaller licenses. For example, a hospital or factory could purchase a license with “priority” access, and then build technology that allows their machines to talk to one another in a more secure way than they could on more regularly used airwaves.

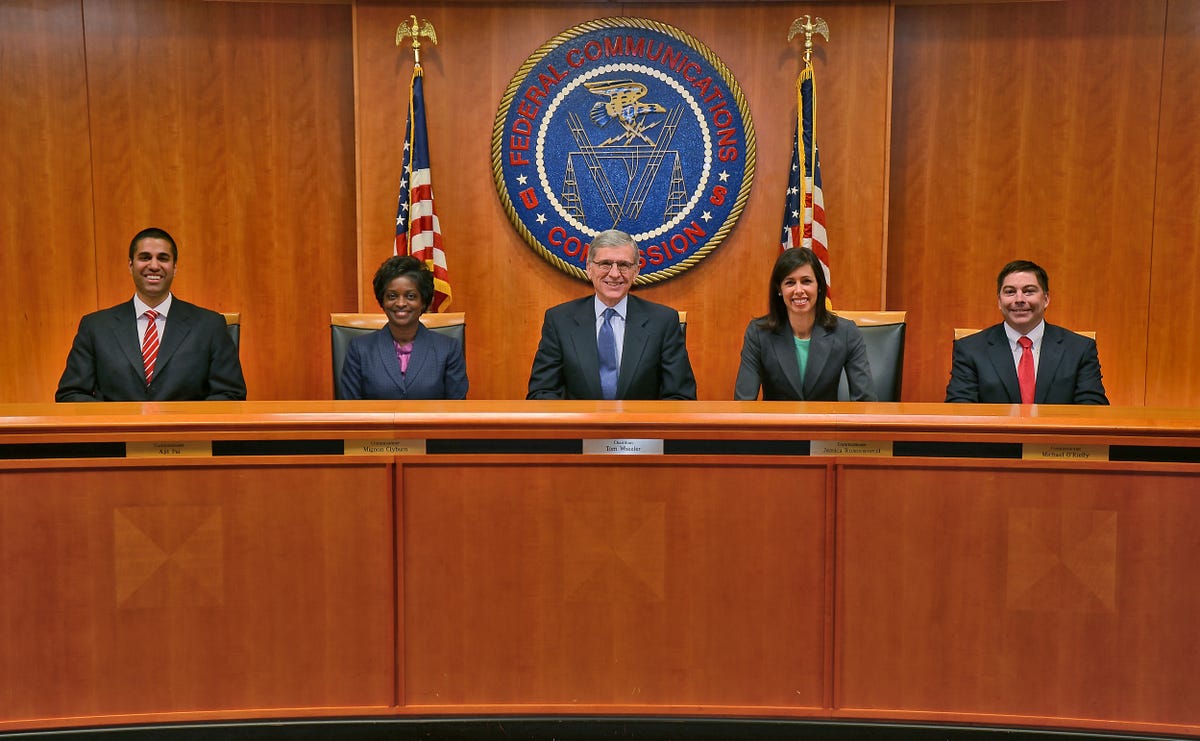

“This is an historic time in the FCC in terms of spectrum allocation,” FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler said during a press conference following the vote. “(Today) we took another step toward more efficient and innovative uses of spectrum by leveraging new sharing rules in technology to create 150 megahertz of spectrum for broadband. The commission’s work to allocate and license spectrum in new and novel ways will deliver massive benefits to consumers, innovators, and our economy.”

In the past when the FCC has needed more spectrum for commercial use, it has worked with the government or other spectrum holders like broadcasters to “clear” or repurpose spectrum. For instance, during the digital TV transition, the FCC moved broadcasters to a different part of the spectrum band and sold at auction to wireless providers. It has also worked with the Department of Defense and other government entities to clear spectrum in other spectrum bands. The FCC has also held auctions to sell this cleared spectrum.

But moving operations for current spectrum licensees is costly and time-consuming. It can often take a decade or more to get spectrum “cleared.” By allowing the spectrum to be shared among different users, it speeds up the process by which spectrum can be used by wireless operators.

“Before when we talked about getting more spectrum in the market, we were looking at a time frame of 10 years or more,” said Mark Gorenberg, a venture capitalist and member of PCAST, who has been heading up the group’s work on this issue. “Now, we’re talking about doing it in three years. That’s a big change.”

In the case of the spectrum the FCC targeted Friday, the radar operations that rely on these airwaves cannot be easily moved. And so, even though the government only used these frequencies in certain regions of the country, they’ve gone unused otherwise.

“That’s not efficient, to say the least,” FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai said during the FCC’s meeting Friday.

While the wireless industry is supportive of the FCC’s efforts to get this spectrum on the market, mobile companies are still leery about the details of how it will work. Specifically, the CTIA trade group representing mobile carriers, says it’s unclear whether wireless providers will have access to spectrum when it will be needed, even with these new licenses.

“While there is cause for optimism, it’s still too early to tell whether this experiment will advance” the government’s goals of freeing up spectrum, said Scott Bergmann, vice president of regulatory affairs for CTIA, in a statement.