When the late Steve Jobs introduced iOS 5 during his last keynote address in June, he touted iCloud as something that “just works” and that users would have nothing to learn.

As it turns out, he was right, but only on his first point.

Not only is there a lot to learn about iCloud, but users have little control over it once they start. So before you jump in, it’s important to know a few things about it.

What is it?

If you don’t quite understand iCloud, you’re not alone. Even Apple hasn’t done the best job of explaining it.

Screenshot by Dong Ngo/CNET

In a nutshell, iCloud is more than just a cloud storage solution that gives you the first 5GB of storage for free; you can use it to store songs, apps, and e-books you’ve purchased from the iTunes App Store or photos shot with your device, on Apple’s servers. It also pushes that data to up to 10 iCould-enabled mobile devices and computers (running iTunes 10.5 or later) that belong to the same Apple ID account. So, for example, when you download an app on one iDevice, that app will also be downloaded to your iPhone, iPod Touch, and to your computer.

For the most part, it’s all pushed in real time, with the speed depending on the Internet connection. So by replacing the old way of syncing your mobile devices with a computer one at a time, you can keep your digital library updated as soon as you download a new song. As far as convenience goes, this seems to be a genius solution. However, you’ll pay a potentially hefty price for the privilege.

The abuse of Internet data and bandwidth

Let’s say you want to download a game that’s 20MB, which is pretty small as mobile apps go. In the past, you downloaded it to your computer using iTunes, then synced it to your iPhone, iPod Touch, or iPad by plugging the devices into the computer. (Or if you chose to download directly to an iDevice, you could transfer that app back to iTunes before syncing to other devices.) This way, no matter how many iOS devices you wanted to put the game on, you just needed to use only 20MB of your Internet bandwidth for the initial download.

Screenshot by Dong Ngo/CNET

Now with iCloud, this changes dramatically. Let’s say that you have an iPad, an iPhone, an iPod Touch, and a MacBook Pro, all with iCloud turned on. Once you have started downloading the 20MB iOS game on one of these devices, the same game will be downloaded to the other three, making the total Internet data needed 80MB. (The data concern aside, you’ll probably find this automatic downloading very cool–I did–at first until you realize that there are four concurrent downloads, instead of just one, going through the pipe. This means that your Internet connection will also be significantly slower for other use.)

Now let’s imagine that you intend to download about 20MB worth of apps, songs, and books from the App Store per day (20MB is equal to about six songs, by the way). With iCloud, your data use jumps to 80MB per day or 2,400MB (about 2.4GB) a month–an excessive amount.

That 2.4GB is more than the first-tier data cap that most wireless carriers impose on a mobile cellular hot-spot router, such as the T-Mobile Sonic 4G Mobile HotSpot and the Verizon 4G LTE Mobile Hotspot SCH-LC11. So watch out when you’re on the road with these iOS devices, especially if you like snapping photos with your iPhone (more on this below).

Screenshot by Dong Ngo/CNET

Note that when you use a mobile cellular router, the router creates a

small Wi-Fi network for the other mobile devices to connect to and share Internet access. But remember that you’re still using a carrier’s data network to access the Internet. So any device connected to a router will still eat up your mobile router’s data allowance, including those you have set not to use cellular data.

Even while at home where your Internet provider offers a high monthly cap (such as Comcast’s 250GB), iCloud could still put a strain on your connection.

iCloud also allows you to sync photos that you take across iDevices via Photo Stream. Yet, because these features also need to use the Internet to upload the data from one device before pushing it to others, they can be even bigger bandwidth killers.

On average, each photo taken by an iDevice is about 2MB in size, so if you take 10 photos per day, the total monthly upload will be about 600MB. And keep in mind that this amount gets progressively larger if you have multiple people in the family using multiple iDevices for snapping photos.

And what would happen if different people shared one Apple ID account? Their privacy might be at risk.

Screenshot by Dong Ngo/CNET

The risk of sharing sensitive information

iOS devices like the iPhone and iPad are designed to build a personal relationship between the product and the user. Unlike a PC, they don’t support multiple profiles, which is why some families buy multiple tablets rather than share one device.

Even with multiple devices families may still share a single Apple ID. This saves them from having to buy the same app more than once; parents can monitor which apps their children use; and they can use one Find My Phone app to know the whereabouts of one another.

Before iCloud, this “sharing” scenario worked well because regardless of how many iDevices a family has, each member could pick and choose which apps he or she wanted on the device when syncing with a PC. With iCloud, however, that’s no longer the case. Anything you buy for yourself will be downloaded on all of the devices instantly. So if you’re using the same Apple ID, there may be times when books or songs not appropriate for kids will end up on their devices.

This could becomes even more embarrassing with Photo Stream, which, as mentioned above, automatically upload photos taken by one device and pushes them to all the others. Note that when you turn on the iCloud’s Photo Stream feature, even photos taken before that will be uploaded from the device and downloaded to others that share the same Apple ID account.

What you can do to keep things in check

Now that it’s pretty obvious that iCloud offers convenience at the expense of excessive use of the Internet, and potential risk of privacy, there are few ways for you to keep it under control.

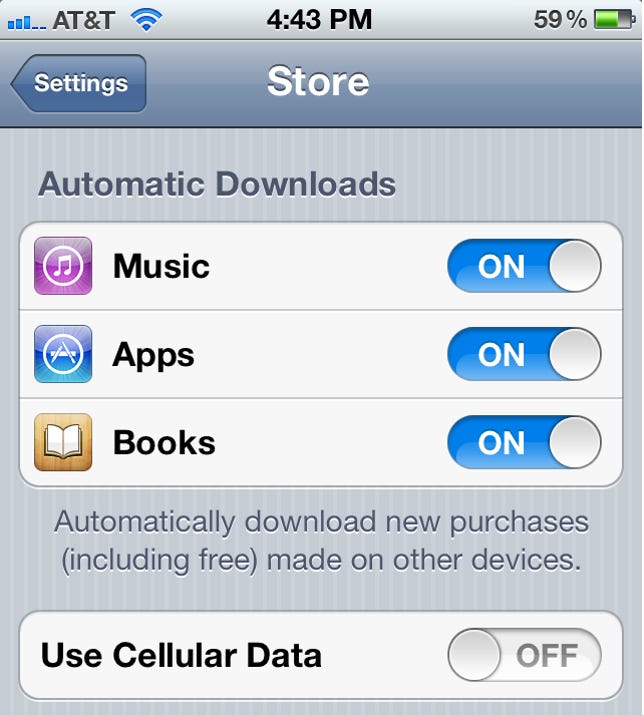

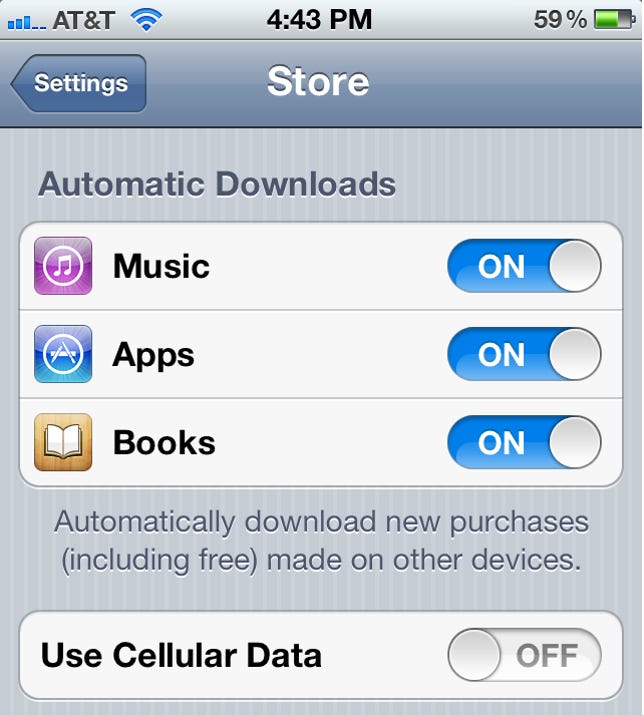

Screenshot by Dong Ngo/CNET

- Use Automatic Download selectively: Turn off types of automatic downloads that are not important to you. For example, you probably don’t need to use the automatic download for e-books on the iPod Touch if you only use your iPad to read books. Also note that your iDevices have different amounts of storage space. Your 8GB iPhone can’t hold everything you want to put on your 64GB iPad, so don’t fill it with unnecessary downloads.

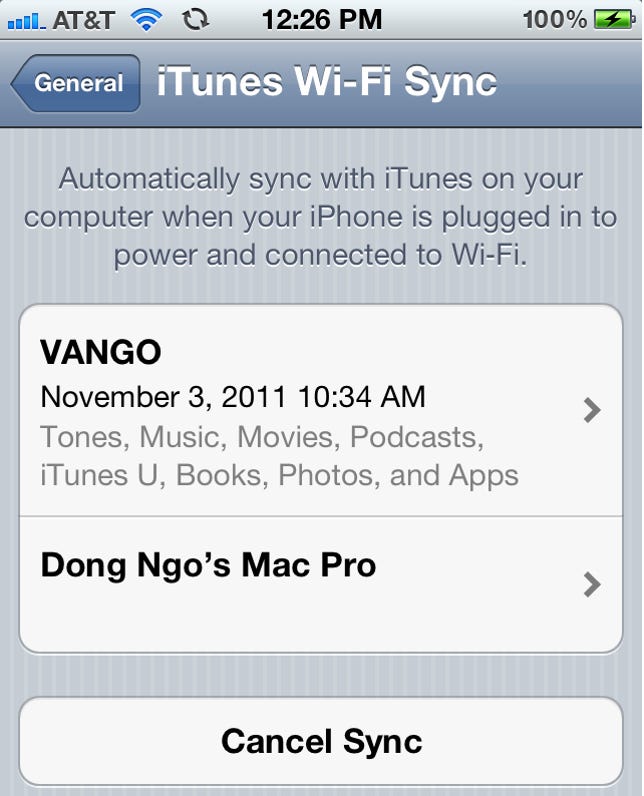

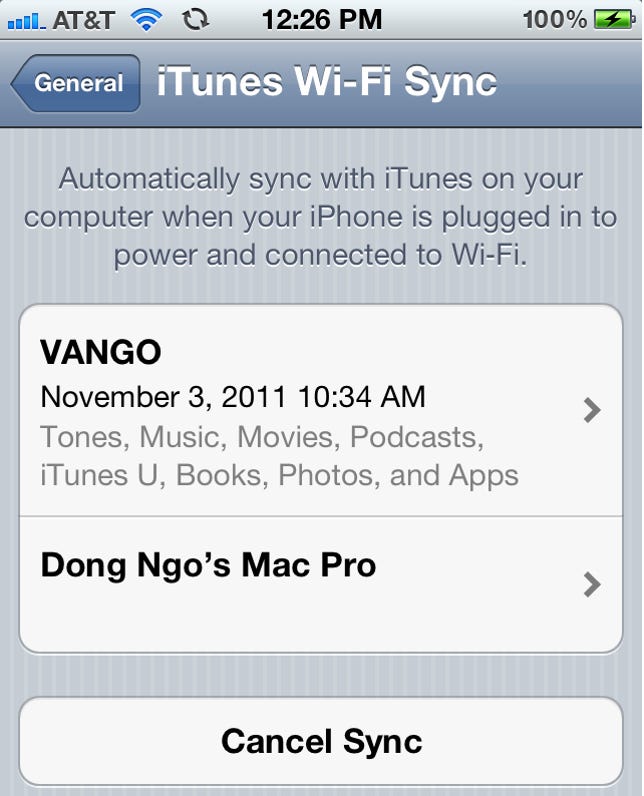

- Opt to use iTunes Wi-Fi Sync instead of iCloud: (Check out this detailed iTunes Wi-Fi Sync How To post.) iTunes Wi-Fi Sync allows you to download purchases from the Apple Store to one computer, then sync them with other iOS devices via your local Wi-Fi network. It basically works the same as plugging the iDevices to a computer without actually plugging it in.

- Use the traditional plugged-in to sync method: This works especially well for those who use the computer to charge the device anyway.

Note that, though more convenient, syncing using iCloud is not always faster than the alternative ways. This is especially true for those with a slow Internet connection.

In regard to privacy, it’s best not to share your Apple ID account with others if you can afford it. It’s also a good idea to use a separate iCloud account from the Apple ID account and don’t lend others your iDevices that share the same iCloud account. You should, too, consider turning off Photo Stream or just be aware that photos you take with your device can be seen by others. Maybe in the future, Apple will offer a way for users to disable this feature on certain photos.

In all fairness, this doesn’t mean that iCloud is not a great feature. It really is and you should definitely turn it on for non-data-intensive applications, like contacts, calendars, bookmarks, and notes. However, like all online storage-based services, you need to exert more control over it or risk finding yourself paying more than you should, or even worse, regretting using it at all.