The news around Nokia has been understandably negative recently, with some calling its collapse “one of the most spectacular implosions in the history of business.”

Last month, Nokia lost its top spot as the world’s largest cell phone manufacturer. Last week, it announced a reduction of 10,000 jobs globally by Q4 of 2013.

So the critical question: is this an implosion, or just transition? The deciding factor may lie with Nokia’s intellectual property.

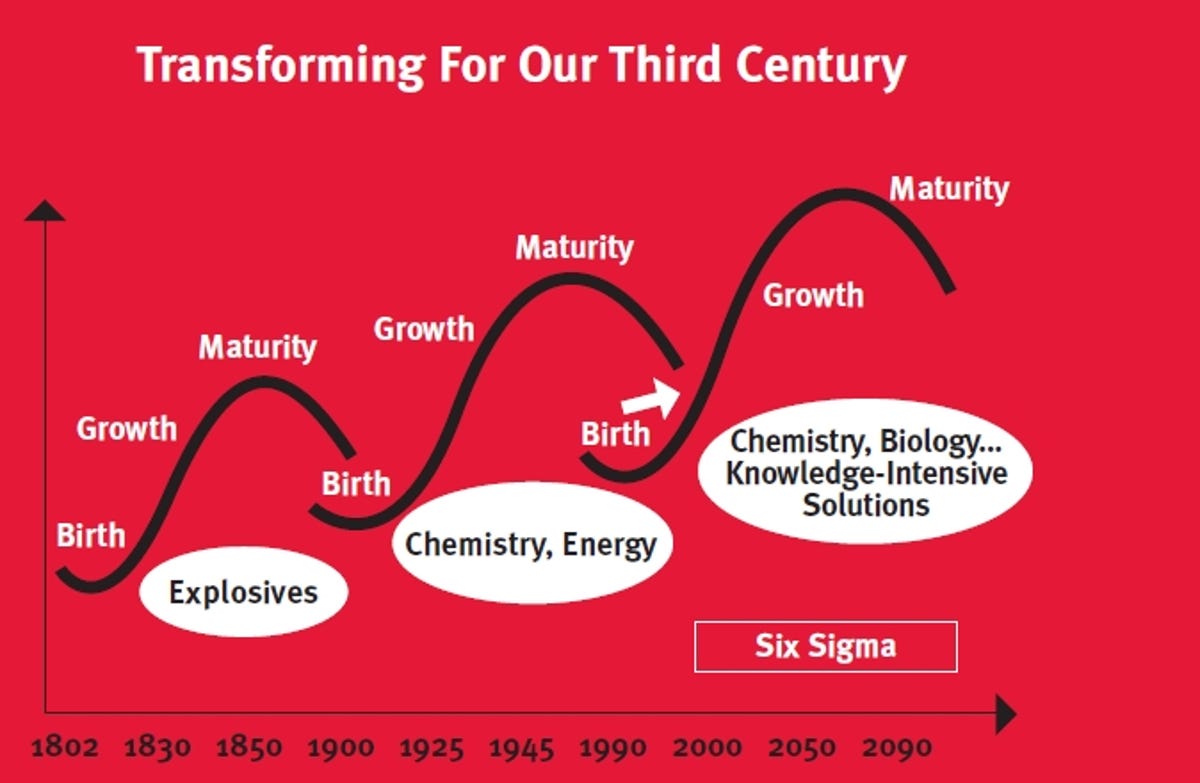

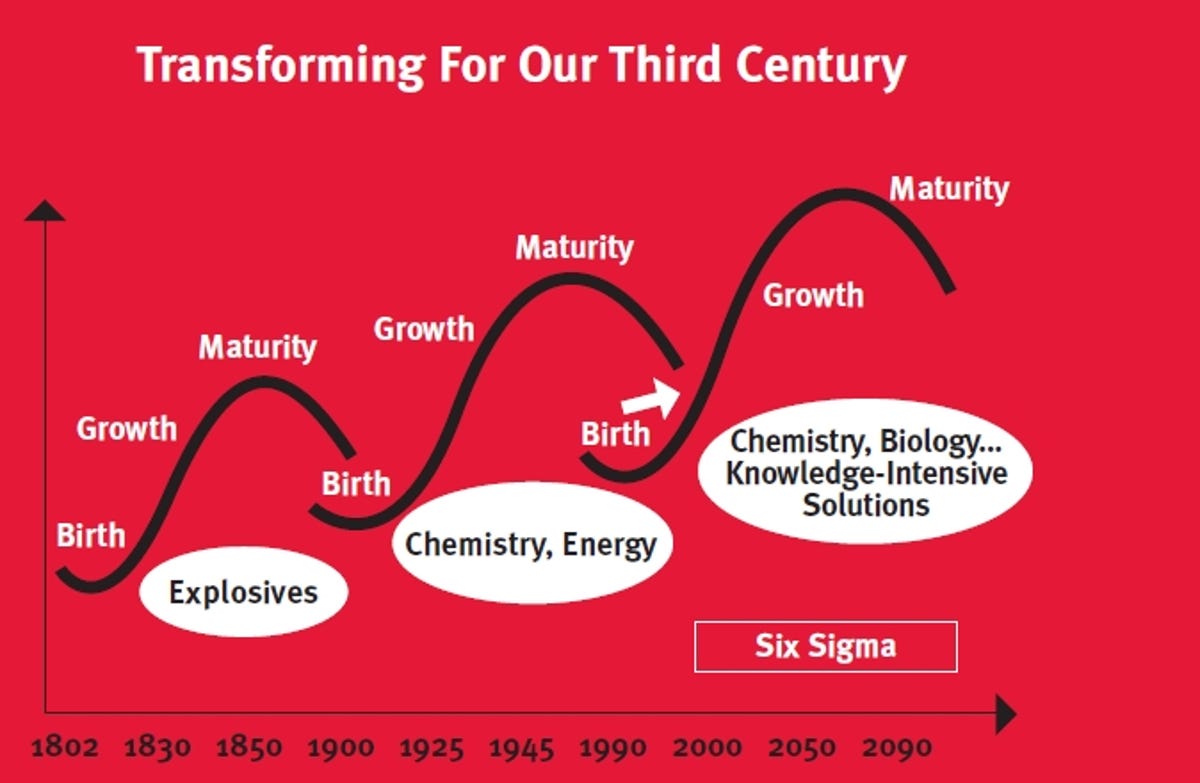

High stakes transitions are a normal part of business evolution. In 2004, I joined the intellectual property (IP) group in DuPont’s Kevlar and Nomex division. DuPont is a 200 year old company which started by making gunpowder, and has made several successful transformations since. From its IP strategy to its product development investments, I saw DuPont clearly understood the nested s-curves of transformation and reinvention.

DuPont 2004 Annual Review

Nokia has been planning its transition to Windows since 2011, and is now starting to deliver on its promises. To support the birth of that platform, Nokia CFO Timo Ihamuotila disclosed last month that Nokia plans to be more aggressive about making money from its IP, which reportedly was already generating over $600 million per year in revenue, including royalties from Microsoft and Apple. Nokia was also was considering the sale of a portion of its patent portfolio.

Typically, patents are most important at three stages in a company’s development: start-up, transition, and wind-down. When in transition, aggressively leveraging IP can help stabilize earnings while product revenue declines temporarily. Nokia recently accelerated its IP monetization efforts with a kind of shock-and-awe strategy, by simultaneously suing HTC, Research in Motion, and ViewSonic over 45 patents in eleven jurisdictions in both the U.S. and Germany.

Many patent professionals immediately recognized Nokia’s move as virtually identical to Kodak’s transition strategy. In the years before its bankruptcy, Kodak generated over $1 billion in licensing revenue. Back in January, it sued both HTC and Research in Motion for patent infringement while trying to run a sales process on over 1,000 non-core digital imaging patents. It also promoted the head of IP, Laura Quatela, to general counsel, then to president and COO.

While few questioned the soundness of Kodak’s IP strategy, many have argued that Kodak did not act quickly or aggressively enough.

Nokia has a long history of successful innovations in smartphones, and that is reflected in its substantial IP arsenal. In the U.S. alone, Nokia has over 8,000 patent grants and 4,000 pending patent applications, despite selling over 2,000 patents to Mosaid last year.

By comparison, HTC has roughly ten times fewer patents and has been relying on Google to come to its rescue for IP protection, such as when HTC tried to sue Apple for patent infringement in 2011. But many of the patents that Google acquired from Motorola have already been licensed to Nokia, so it is unlikely that HTC will have much leverage in these negotiations.

It’s now clear that Nokia isn’t going to fall into the same trap as Kodak with respect to IP. Although it dismissed several senior executives last week, I wouldn’t be surprised to see Paul Melin, vice president of intellectual property at Nokia, elevated the same way Laura Quatela was at Kodak.

In general, there are four primary objectives in developing a patent portfolio:

- Remove infringing products or features. In this case, a company sells products or services covered by innovations they have patented; and uses their IP to stop others from selling products that are using their inventions without permission.

- Sustain a product ecosystem. In this situation, an IP owner sells products where their IP may be necessary, but not sufficient to sell a product, and needs broad cross licenses with suppliers, customers and even competitors to ensure that products can come to market.

- Generate revenue from the assets themselves. In this model, typically, either the patent owner receives payment from licensing agreements, or the owner sells the portfolio outright.

- Improve underlying valuation: Here, an IP owner uses patents to reflect innovative activity, improve valuation, reduce cost of capital, and ultimately provide investors with an important underlying asset that could be leveraged in any of the above ways. In my role at MDB Capital, the first thing I look for is if a company has, or can obtain, a dominant IP position to support their innovations.

At this stage in its transition, revenue generation is clearly Nokia’s key patent strategy. After $650 million in revenue from IP last year, it makes sense that the company would focus further on IP as a business. Typically, IP licensing produces almost pure profit; considering Nokia lost over $1 billion in 2011, it’s possible that a focus on IP could very well make the difference between transition and implosion.