Symantec

The wearable market is currently estimated be worth around $14 billion and it’s on the way up. According to AB Research, by 2018 over 485 million wearable devices will ship each year.

Fitness trackers are just one part of the market, but they’re a high profile one and it’s little surprise that they’ve fallen under Symantec’s security microscope.

Symantec’s whitepaper, “How safe is your quantified-self (PDF)“, looks at the whole fitness tracking movement, from dedicated devices such as the Fitbit or the Jawbone, to apps that use a smartphone’s inbuilt sensors, and through to programs that require a user to input information manually.

The report paints a picture of a new market segment that is in need of better information protection.

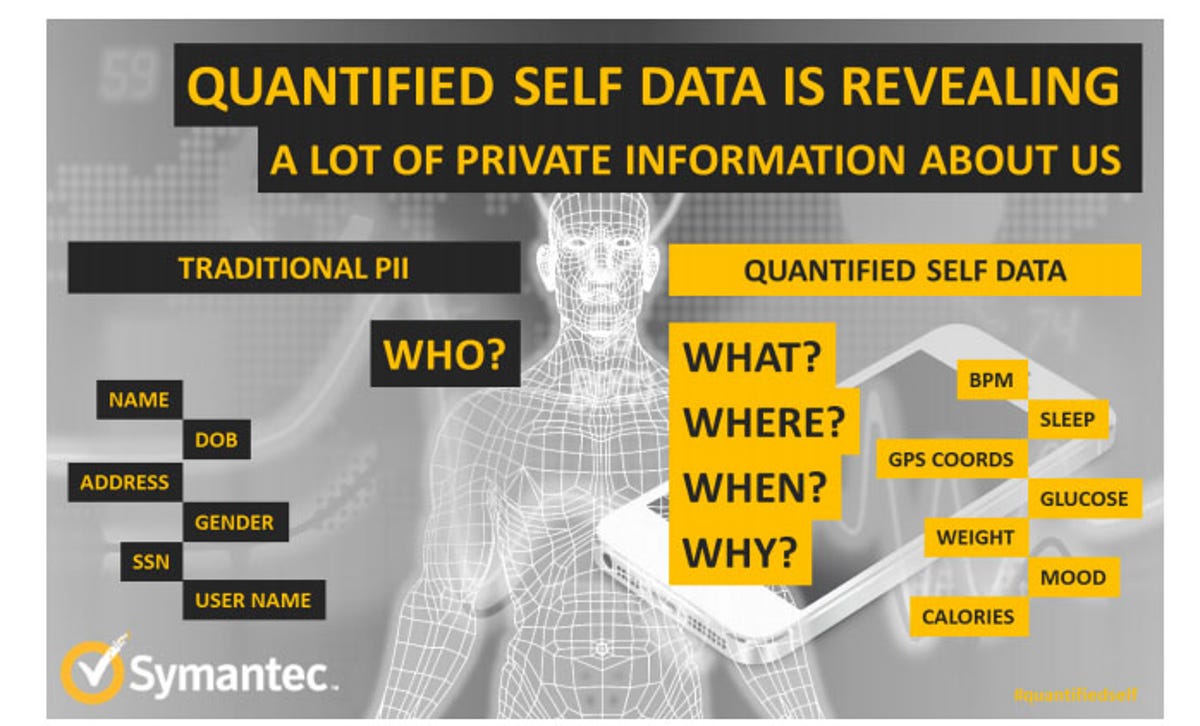

Symantec notes that the sort of information being collected by what it terms ‘self-trackers’ differs significantly from “traditional” personal information, such as name, date of birth or address. Self-tracking information can be as varied as weight, BPM, sleep times, location data, or even things as personal as sexual activity, emotional state, or drinking habits.

In terms of security issues, just some of the troublesome areas that report highlights include:

Vulnerable Location Tracking: Symantec found that all the current wearable fitness models were vulnerable to location tracking, but says that those using Bluetooth LE are particularly at risk.

The company used the Raspberry Pi PC to build a number of cheap Bluetooth scanners discovering that:

By placing a number of scanning devices at various locations, it is possible to scan and locate a device by identifying the hardware address and measuring the relative signal strengths between scanners and the device, it is possible to get an approximate fix on the physical location of the device.

Poor password protection: A staggering 20 percent of apps transmitted their password data “in the clear” — that is with no encryption at all. Given the evidence that many people use the same or similar passwords across multiple services, this is cause for concern.

Lack of privacy policy: Only 52 percent of the apps that Symantec examined made their privacy policies available to users.

Unintentional data leakage: Symantec’s report gives a rather specific example of one app that shares some rather personal information:

In one app that tracks sexual activity, the app makes specific requests to a certain analytics service URL at the start and end of each session. In its communication, the app passes a unique ID for the app instance and the app name itself as well as messages indicating start and stop of the tracked activity. Based on this information, the third party who receives the data would be able to know the sexual habits of the owner of the device, granted that the real identity of the device owner may not be associated with the ID.

Sadly, Symantec can’t offer too many recommendations to users of tracking apps and devices, other than the usual “use strong passwords” and “be careful about social sharing”.

Instead, the call seems more firmly in the court of the app developers and device manufacturers. Secure session management, following the best practices for passwords and better protocols for transmission of secure data are just some of the recommendations.

Data from AB Research says that in the first six months of 2014, there was a 62 percent growth in the use of health and fitness apps. This is a market experiencing some very rapid growth, and unless the devs and manufacturers jump on board soon we don’t think this is the last time we’ll be hearing about security issues with fitness trackers.