BARCELONA, Spain–High dynamic range (HDR) photography has largely been the province of photo enthusiasts willing to put up with its hassles, but Dolby Laboratories hopes to bring it to the masses with a semi-proprietary technology called JPEG-HDR.

HDR photography began as a way to compensate for cameras’ shortcomings compared to the human eye. The biological image sensor can capture a much greater range of dark and bright tones, whereas cameras typically can capture only one, the other, or something in the middle.

That means problems with photos in areas with a wide range of lighting- a scene where someone is standing in a shady foreground when there’s a sunlit background, for example. Or the one that constantly frustrates me, stained-glass windows in cathedrals.

With HDR, a camera takes a series of shots at different exposure levels, and a computer combines them. It’s getting easier as software automates the process, and it’s even a built-in feature with the iPhone 4 and upcoming HTC One X.

But there’s still plenty of room for improvement, and Dolby hopes it’ll bring some to market with JPEG-HDR, which the company debuted at the Mobile World Congress show here in Barcelona.

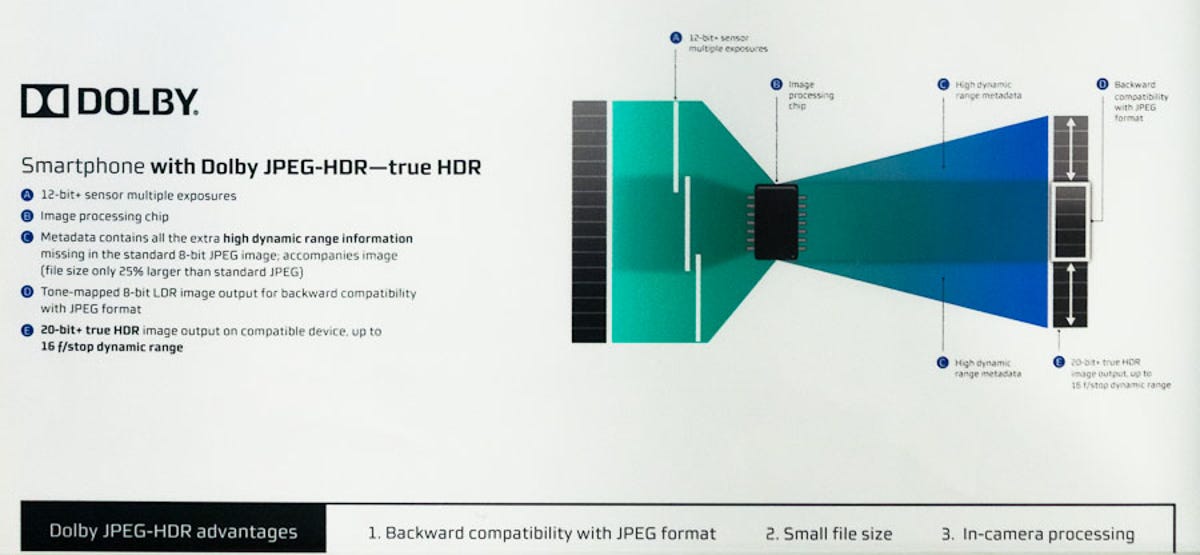

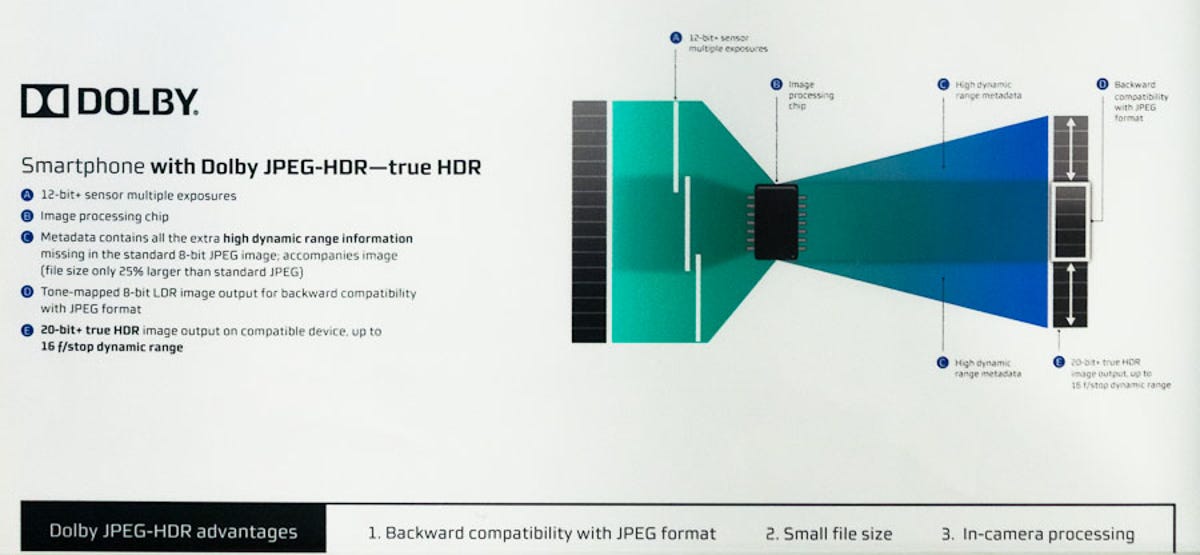

JPEG-HDR uses a proprietary processing algorithm to combines multiple exposures. That, in and of itself, isn’t particularly new, but what is comes next: Dolby creates from this an HDR image that’s backward compatible with ordinary JPEG.

Dolby, Qualcomm shed light on HDR tech (photos)

You need special software to explore the full details of the HDR image. But without it, you can see the “tone-mapped” JPEG constructed from the HDR data, said Jean-Marc Matteini, senior director of marketing for imaging at Dolby.

JPEG only has room for 8 bits of data per color value at each pixel, meaning that there are a maximum of 256 levels separating bright from dark. JPEG-HDR can handle 20 bits or more. A 20-bit depth is enough for 16 f-stops of dynamic range, which is what the human eye can detect, Dolby said.

“We store the extra range as metadata in the header,” Matteini said, referring to section of a JPEG file that ordinarly stores metadata such as captions and camera information. A JPEG viewer that can’t decode Dolby’s extra info just skips over it.

Personally, I like all the HDR work that’s going on, overall, though the surreal images people sometimes deliberately create with HDR aren’t to my taste. And I prefer images that show a broad dynamic range in one view rather than some kind of an interface to explore light and dark tones. I was glad that the tone-mapping settings Dolby used in the very limited examples on display showed a relatively normal view of the scene, not one of those over-the-top images with halos and crispy grunge textures.

Stephen Shankland/CNET; poster image by Jonathan Kong/Dolby

Qualcomm showed off JPEG-HDR on an Android tablet prototype at the show. Its demo showed my bugaboo, the cathedral photo. Tapping on the stained-glass windows exposed them properly while everythinge else went nearly black, and tapping on a dim part of the interior showed it off while the windows washed out to complete whiteness.

Part of the challenge in taking an HDR photograph is capturing images in rapid sequence to minimize problems of subjects such as people or leaves moving from one frame to the next. “We have a great framework for image capture which enables that sort of capture,” said Phillippe Decotigne, a Qualcomm product manager. Qualcomm’s processors can handle 13 images per second.

Dolby isn’t the first to tackle HDR imaging challenges. Perhaps the most prominent alternative is JPEG XR, an “extended range” file format originally developed by Microsoft but now an industry standard. It can accommodate much a broader dynamic range than JPEG.

But JPEG XR uses a different compression algorithm altogether (one that’s better, Microsoft argues), which means you can’t simply see a JPEG XR file unless you have software that knows how to decode it.

Dolby licenses it technology to others, and JPEG-HDR is another example of that business in action. However, the terms aren’t set yet, Matteini said.

“Maybe the decoder is free,” so that it’s easy for others to view the files, but Dolby would license the encoding technology so that makers of cameras or image-editing software would have to pay.