MIT Media Lab

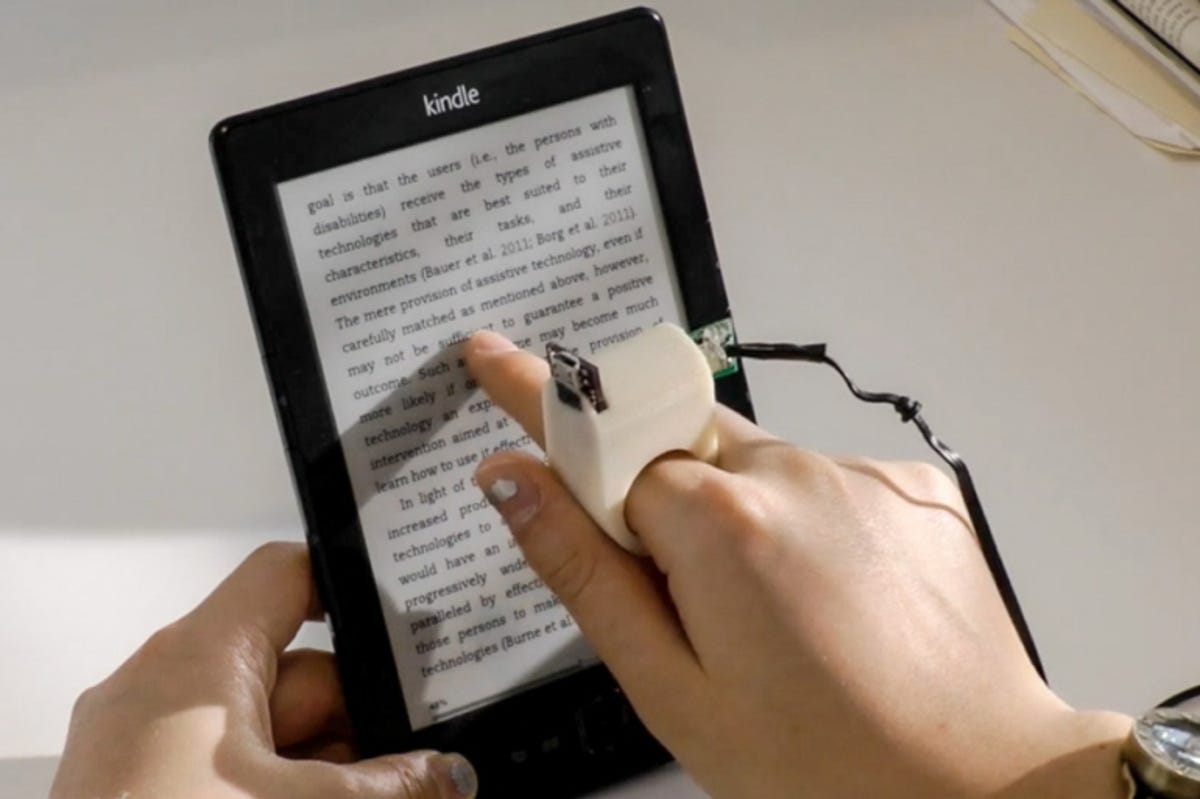

A prototype device developed by researchers at MIT’s Media Lab would allow the blind to read with their finger without having to learn Braille. The FingerReader, mounted on the user’s finger, is equipped with a number of sensors that allows it to read text on a page on behalf of the reader.

While using a computer, a blind user can make use of software that converts text to speech for web pages, word processing documents, PDF files and emails — but printed text is a different matter. The FingerReader brings text-to-speech to the real world by guiding the user’s finger along a line of text, generating the corresponding audio in real-time.

Related articles

- Lend your eyes to the blind with Be My Eyes app

- Sign-language translator uses gesture-sensing technology

- Haptic app helps visually impaired learn math

“You really need to have a tight coupling between what the person hears and where the fingertip is,” said MIT graduate student Roy Shilkrot, paper co-lead author with postdoc student Jochen Huber. “For visually impaired users, this is a translation. It’s something that translates whatever the finger is ‘seeing’ to audio. They really need a fast, real-time feedback to maintain this connection. If it’s broken, it breaks the illusion.”

The device relies heavily on the camera feed and its associated algorithms. When the user puts their finger on the page at the start of a new line, these algorithms make a bunch of guesses about where the text’s baseline sits, based on density — text ascenders and descenders are less dense than the median.

This then allows the FingerReader to constrain the guesses it needs to make for each new frame of video as the user moves their finger. It can then much more easily track each individual word, cropping it out of the image and sending it to software that parses the characters and translates them into audio in real-time.

For the prototype, the FingerReader was tethered to a laptop, upon which these calculations were made, but the team is now developing a version of the open-source software that will run on Android phones.

The team also tested two methods of guiding the user’s finger: haptic motors on the top and bottom of the finger that vibrated when the user’s finger started to move away from the line, alerting them to move their finger back up or down the page; and a musical tone that sounds when the finger strays. Users testing the system evinced no preference for one or the other, so the team elected to go with the audio sensor, since the haptic motors add weight and bulk to the device.

The device has applications beyond helping the blind to read, too.

“Since we started working on that, it really became obvious to us that anyone who needs help with reading can benefit from this,” Shilkrot said. “We got many emails and requests from organisations, but also just parents of children with dyslexia, for instance.”