Cloud gaming runs hot and cold, and now it’s hot again, thanks in part to Nvidia extending its GeForce Now (GFN) service from its Shield streamer to Mac and PC clients. Unlike some services it’s often compared to, like PlayStation Now, with GFN the cost of playing doesn’t include the games. To use it, you need a GeForce now account as well as a Steam, UPlay or Battle.net account, the latter to run Ubisoft and Blizzard games, and you have to own or license the game via one of those three.

Nvidia doesn’t really get involved. Cloud syncs are handled by the respective services, which also handle account management. When you click Play in GFN, it takes you to the external service; in Steam, for example, it takes you to the game in your library where you hit “play” again. GFN basically acts as a rendering and streaming engine.

There are some free-to-play options as well, but they’re not trials, they’re just games you can usually play for free, like DOTA 2. And you’ll need a consistent 25Mbps or better internet connection, a 5GHz or wired connection to your router, and a computer that can handle the decoding on your end.

It’s currently in free beta, and Nvidia’s doling out beta accounts slowly. There’s usually a wait: My personal beta request took about three weeks to come through.

But it won’t be free after launch. A lot of unknowns swirl around the service, especially price and availability. When it was announced at CES 2017, Nvidia said the pricing would be $25 for 20 hours of play (equivalent to about £18 and AU$32) — Nvidia declined to tell me if that’s changed, what it expects the pricing structure to be or when it will be out of beta.

It’s not for most hardcore gamers

Here’s the rub: The game selection and interface feels like it’s designed to appeal to hardcore gamers, not intermittent ones. But the announced pricing and policies will likely only appeal to intermittent gamers or Mac owners who have few alternatives for playing Windows-based games.

There’s understandably been pushback in the forums on the 25-for-20 figure from beta testers, which seem to consist of people who game a lot or want to but can’t afford the hardware.

For instance, SteamSpy estimates (really roughly) that on average, people play PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) for about 12.5 hours every two weeks. That works out to 325 hours a year, or 16.3 20-hour gameplay chunks at a total of $410 for the year, not including the game. That does sound really expensive, especially when you compare it to the price of a console or an $800 gaming desktop. It also sounds expensive when you compare it to other streaming services, like Netflix, whose 4K streaming plan costs half that, including content.

But I don’t think Nvidia really wants people to use this as their main gaming system if they’re going to be playing lots of hours — that would require a lot more resources to keep everyone happy. So the high price functions as a filter. Beta testers are also annoyed because the beta has been free and many of them won’t be able to afford the service for the number of hours they play if it goes live at the proposed price.

Plus, hardcore gamers are the ones buying Nvidia’s high-end GPUs. GFN seems like it’s supposed to complement these existing systems when you’re away from your primary system, not replace them. And given some other constraints, you probably don’t want GFN to be your sole game system, anyway.

A lot also depends on how Nvidia structures the billing. If you can pay in 20-hour increments or have a digital wallet that’s a lot more attractive for casual users than having to pay for a specific number of hours up front. On the other hand, gamers who put in a lot of hours would probably be happier with an all-you-can eat plan, even if it has some sort of cap. (“Unlimited” in the cell carrier sense of the word.)

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageTwice the Ubisoft, twice the fun?

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

When it’s good, it’s very good

GFN gets high marks for performance, and when it’s working right, it’s addictive. I can play at my desk at work, on my Mac (only on Wi-Fi because game ports are typically blocked on our work network) or on any random laptop I’m reviewing. No two-hour downloads to install games on a system at home. There’s really very little friction.

It can generally run on almost any PC or Mac with a CPU or GPU that’s less than 10 years old as long as it supports DirectX 9 and has a 64-bit operating system (here are the detailed system requirements).

Installations are nearly instantaneous, because they’re communicating server-to-server, though it takes just as long for a game to launch as it would normally. When you launch a game, Nvidia starts up a Windows virtual machine to run it, and when you quit the game, the VM shuts it down. That’s how it magically lets you play on a Mac.

And generally, games run well, as long as your network is decent and you stick to 1,920×1,080 resolution. The rendering takes place on the server, so you get game frame rates akin to a GTX 1070 (though it’s running a GTX 1080-class GPU). I’ve played on a Mac Pro, MacBook Pro, HP Spectre x360, midrange ROG Strix and even a cheap Acer Swift 1 that didn’t meet the minimum specifications to run the app.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageGeForce now screens (top) look less detailed that those from the same system running the game (bottom).

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

I did experience some glitchiness or lag occasionally, but it tended to be in games that are glitchy or laggy in general. Yes, I’m looking at you Bioshock Infinite. One persistent issue I’ve had is random audio dropout. Across any network, gaming ranges from really good with just a little stutter to a perennial “connecting…” message to no response at all, though it depends on the game. Some detail may come in blurry at first and then progressively render more sharply, though this happens more on menus and cutscenes than during gameplay. That’s all over Wi-Fi, though. When I ran into trouble, switching to wired made all the difference.

However, no matter how high the server-side frame rates, it’s still streaming to you at either 60fps or 30fps, depending upon your monitor and connection type (HDMI or DisplayPort).

And you still need to buy a game-quality keyboard and mouse, and a wired controller comes recommended. If you want 60fps, you’ll also need either a gaming laptop (their built-in screens support higher refresh rates) or an external monitor connected via DisplayPort.

It includes early access and pre-early access of some games

As long as they’re high profile, you’ll find some as-yet-unfinished games on Steam, such as the perennially early-access Factorio and Rimworld, as well as the PUBG Test server.

You can play any Steam game

By launching into Steam, you can play anything in your Library; you’re not limited to Nvidia’s selection. There are caveats, however. Because of the ephemeral and sandboxed nature of virtual machines, you can’t save anything locally. That means unless it syncs via Steam Cloud you have no way to save progress. You also need to reinstall every time you launch, though given how fast it is it’s not really a pain.

Then there are the drawbacks.

Watch the clock

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageOuch!

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

You have four hours per session and not a second more. Yes, Nvidia suggests that you simply log out and log back in, but that didn’t stop it from summarily and without warning tossing me out of Doom and closing the VM session. (Probably a bug; it’s supposed to provide a five-minute warning.)

In games that only allow checkpoint saves, though, it’s unacceptable to bounce people out at a random point even with a five-minute warning. All that does is give you enough time to resign yourself to losing your progress.

It’s unclear if the four-hour limit will remain past the beta period, but I’m sure there will be some kind of time limitation, so hopefully Nvidia will fix the experience. You can avoid it by relaunching periodically, such as after every checkpoint, though that’s annoying and sometimes infeasible.

Occasional gamers may put up with having to track gaming time, but if you’re hitting the max every other day, that’s a major pain. And it means you can’t pause the game, go away for awhile and pick up where you left off. It’s less of a “gaming PC on demand” than a time share.

I forgot I was uploading a video in the background.

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

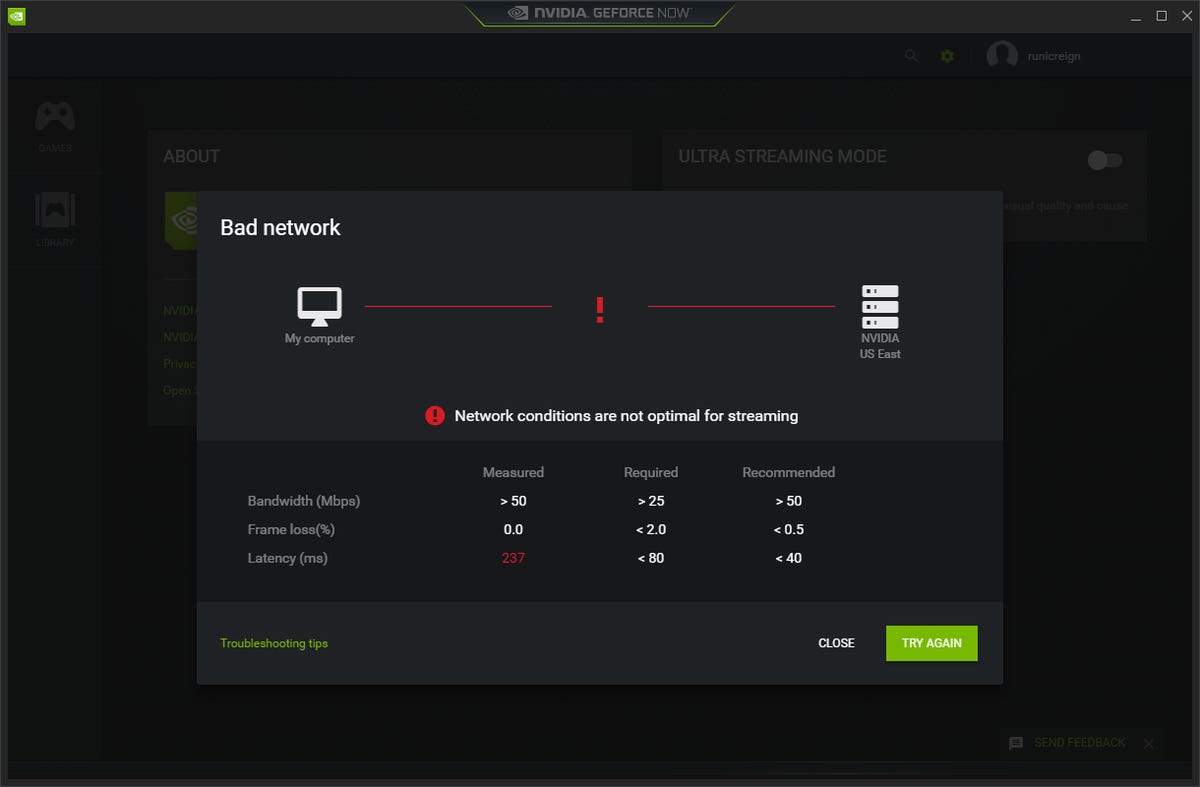

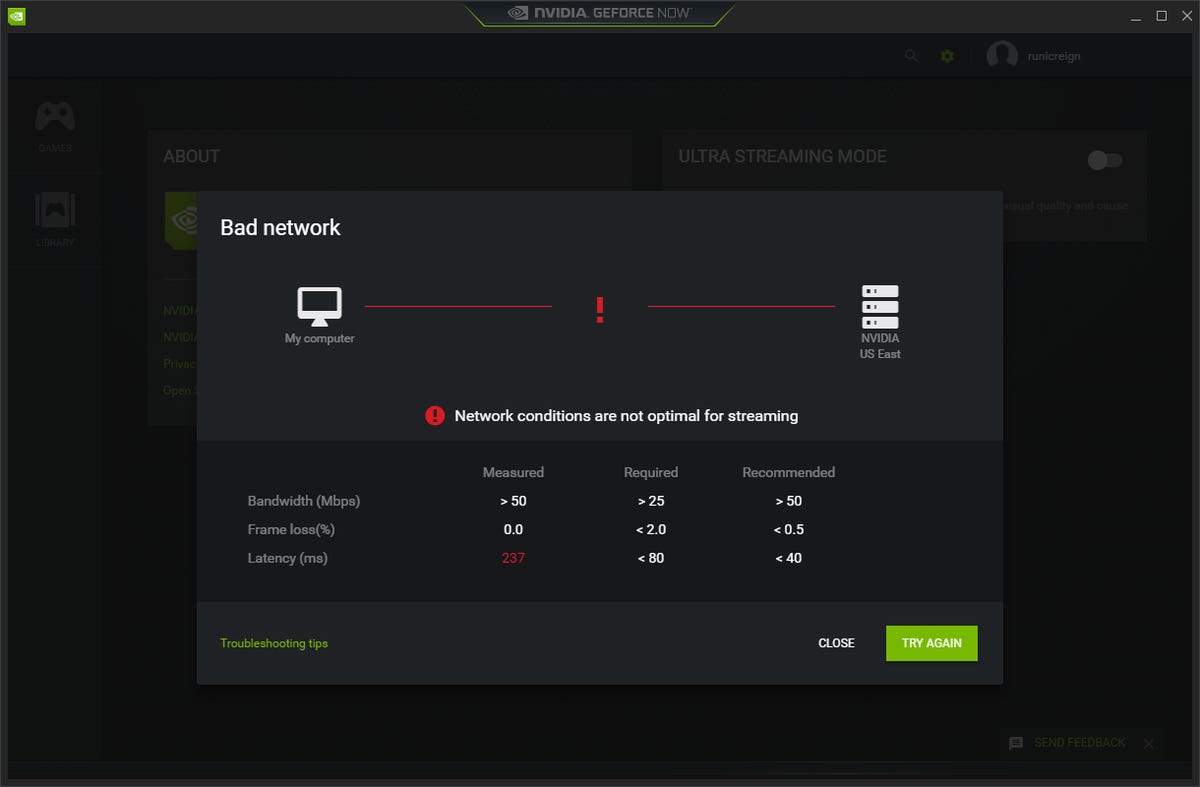

Good bandwidth is not enough

Speed should be the same on most hardware, because that’s not the limiting factor with cloud gaming, where the game runs on the remote server. The gaming experience *does* depend on your network latency, which in turn depends in part on network congestion. So if you want to CS:GO in the evening while people who share your connection want to Netflix, with or without the chill, that may be a problem. (You can pull up a useful readout of your network and streaming status in game with ctrl-alt F6 on PC or cmd-option-F6 on Mac.)

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageSo much for a restful afternoon of running amok.

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

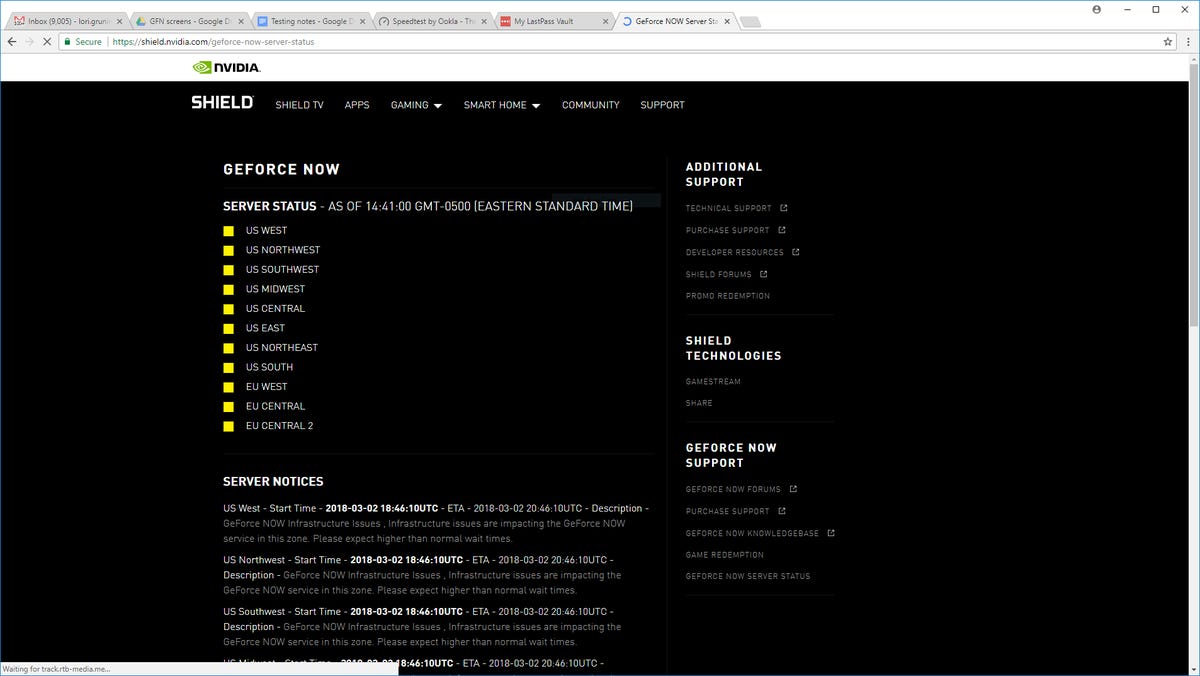

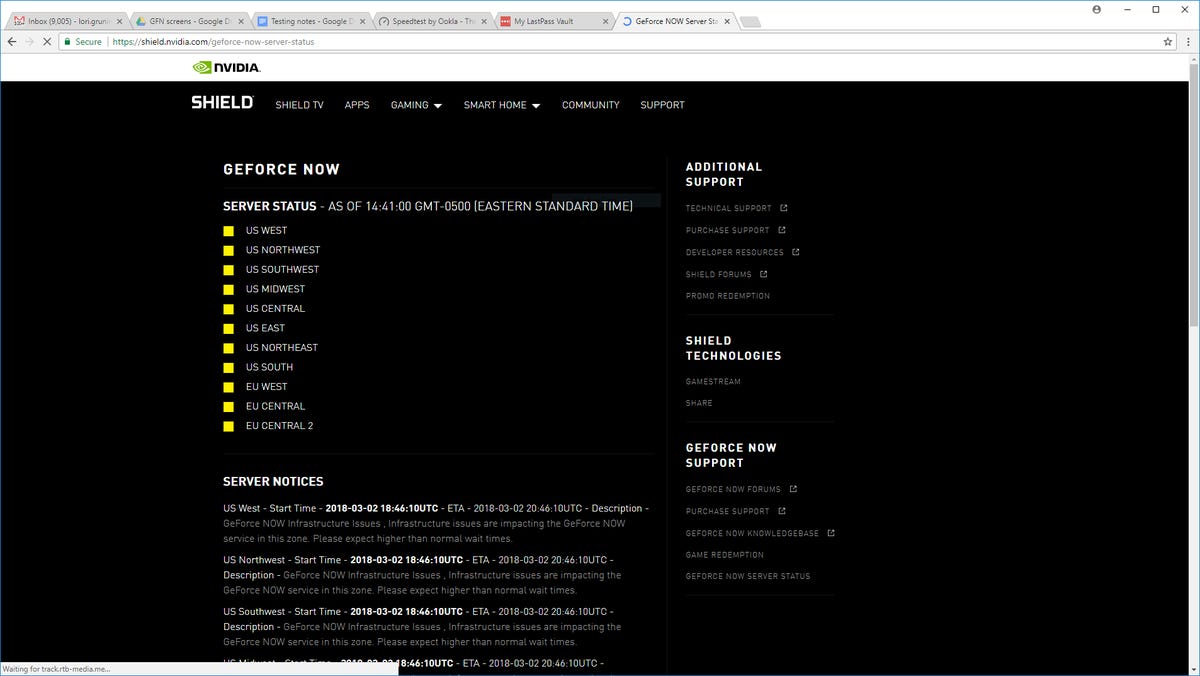

It won’t always want to play when you do

One day, I unrolled my mouse mat, connected my mouse, got my water and munchies, settled into my chair, opened my laptop and launched GFN — only to be greeted with a dialog informing me that it was having technical issues and to try again later.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageI just wanted to pop in to take a screenshot and was greeted by this message.

Screenshot by Lori Grunin/CNET

Of course, this is one of the problems with any streaming service, but how true that is depends on what kind of uptime and capacity guarantees Nvidia makes.

If you game to the beat of your own drummer, you’re out of luck

Nvidia told me that its game selection criteria will always be based on popularity. So if you like AAA games, good for you! More than three quarters of the games in my Steam library aren’t popular enough to merit inclusion on GFN, and a lot of those don’t support Steam Cloud sync (I learned the hard way because I forget to check before I buy. My most painful example: Bendy and the Ink Machine.) If you’ve got old games or games you bought elsewhere, like GOG, you’re going to need a local system.

The games you play may disappear

In this sense, GFN has a lot in common with other content streaming services. For instance, on Feb. 7, 2018, a handful of games disappeared from the service with a forum message stating “The following games are offline due to technical issues. We’re exploring solutions and will advise as further updates are available.” Three Total War games and two Football Managers, at least one of which doesn’t cloud sync. A month later, still no word.

The outside world doesn’t exist

With a few exceptions, you can’t get anything from outside the game into the game and vice versa. For one thing, that means no downloadable mods. If you can get to them from a game menu or from within Steam, then you’re good. You can use the Steam overlay, but any captures are only sent to Steam; they’re not saved to your hard disk as usual. The Windows Game Bar does save to your local hard drive, but only on Windows.

Gaming: See all of CNET’s coverage

Laptops: The traditional alternative