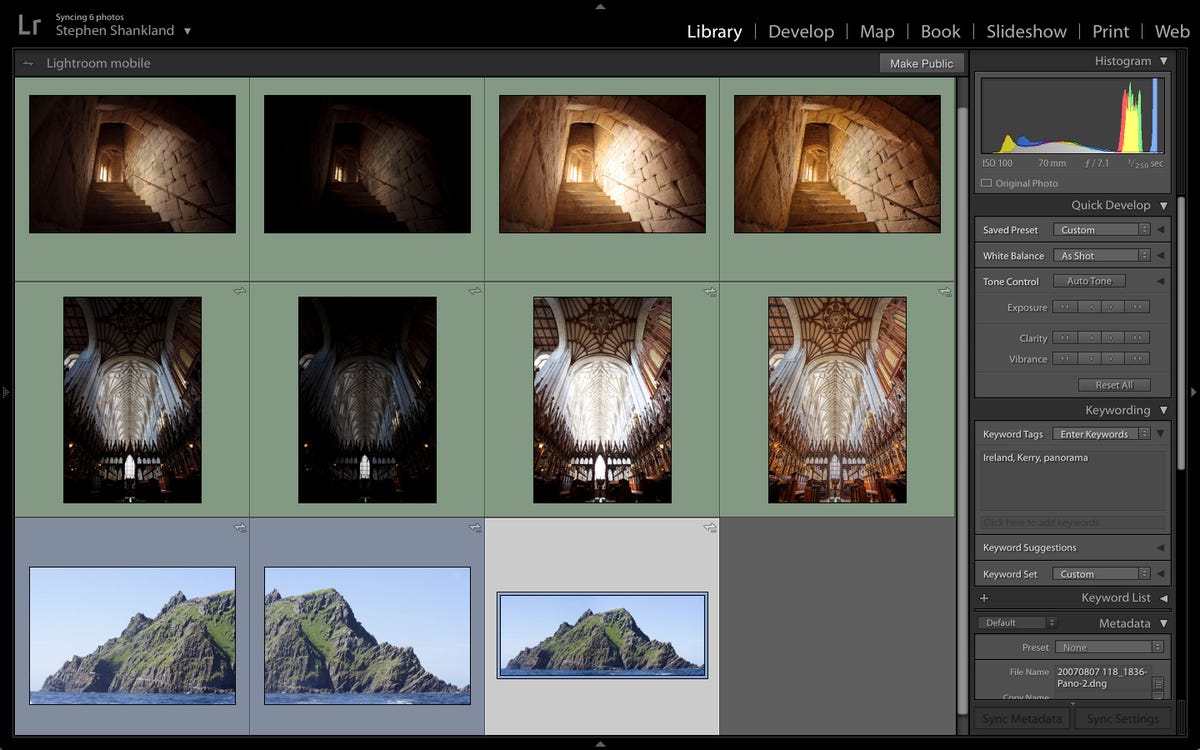

Screenshot by Stephen Shankland/CNET

Adobe’s photo editing and cataloging software now gives photographers new ways to merge multiple shots into one. More and more, photos can be transformed into something beyond the single frame you first snapped.

Adobe Systems’ new version of Lightroom isn’t the first program to let photographers merge multiple photos into panoramas or high dynamic range (HDR) images. But it may be the program photographers actually use for those jobs.

Here’s why: For years, photographers have been able to use software like Adobe’s Photoshop to join a sweep of individual photos into a single panoramic image. Other options like HDRsoft’s Photomatix, Google’s Nik HDR Efex Pro and Oloneo’s PhotoEngine let them merge multiple shots of the same subject into an HDR image that captures both highlights and shadows.

But Lightroom is widely used by photography pros and enthusiasts, and building panorama and HDR support straight into the software makes those features easier to use. Lightroom also offers a compelling advantage in its approach: its Digital Negative (DNG) file format preserves more of a photo’s image quality and editing flexibility.

The update shows how photos can have a life that extends beyond that original single snap you took. Most people are fine using their phones to take photos, but for those who want to go farther, digital photography offers countless possibilities.

HDR and panoramic images are examples of one fruitful area of development called computational photography. With the technology, software running on a camera, phone or computer processes images into something more than what the camera can capture on its own. Computational photography is already used for things like fixing lens flaws and correcting images shot in the shade so people don’t look so blue.

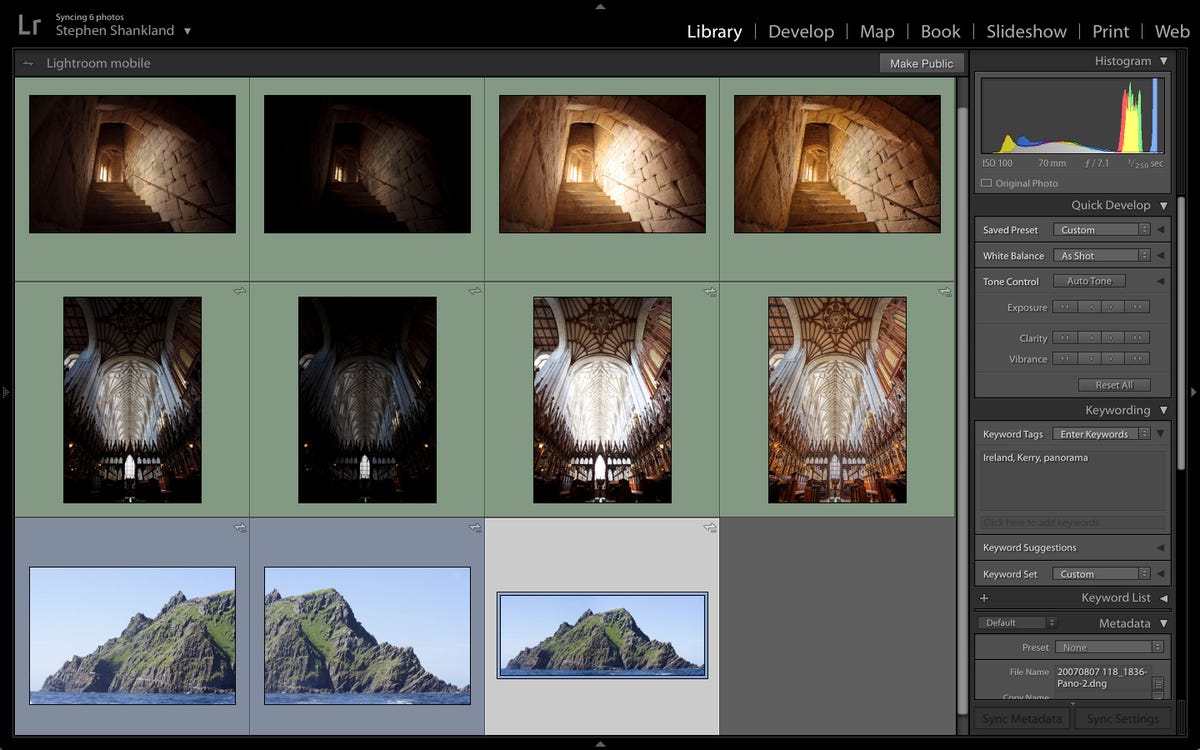

Screenshot by Stephen Shankland/CNET

The new Lightroom also adds other new features. Among them are face detection to organize your photos by person; the ability to selectively mask out patches from the software’s “graduated” and “radial” filters; and a processing boost that dramatically speeds up editing changes. For a more detailed look at the software, check out the full assessment from my colleague Lori Grunin .

I’ve been testing the software for a week, and I found having the new features integrated into Lightroom makes a huge difference. Before, I’d have to select photos, edit them, export them in the JPEG or TIFF file formats, merge them into panoramas or HDR shots with some other program, then re-import them back into my Lightroom catalog.

It’s been fun poking back through my archive and building HDR and panoramic shots that I took but never assembled. The new version — Lightroom 6 if you buy a perpetual license for $150 or Lightroom CC if you pay $10 a month for a Creative Cloud subscription that also includes Lightroom Mobile and Adobe Photoshop — unlocked a small treasure trove I’d forgotten I’d amassed.

The HDR and panorama support has been a long time coming. It was way back in 2008 that Adobe first told me they were on the radar for Lightroom. One reason for the wait was that Adobe had to update its DNG file format to handle the new technology. The 2012 DNG revision included support for transparent pixels needed for patchy panoramas and math changes to accommodate the greater numeric range stored in HDR shots.

Lightroom is geared in particular for photos shot in that require more processing work but offer higher image quality than the mainstream JPEG format. DNG preserves raw advantages like color flexibility and dynamic range.

The panorama feature can stitch together images taken side by side vertically or horizontally. You can even stitch HDR images together into a panorama. I found Lightroom stitched the panoramas very well for the most part, handling awkward joins like water and tree branches well for the most part. But with big jobs, Lightroom can pound your computer’s processor.

HDR and panoramas also can have a hard time with people and leaves that change position from one frame to the next. Adobe generally handles the situation with de-ghosting software, though.

Some photographers like HDR photography for its ability to imbue scenes with otherworldly tones, spooky skies, and psychedelic textures. Adobe’s version of HDR, though, sticks more closely to a photorealistic look that just does a better job of capturing shadow and highlight detail. That conservative approach might displease some photographers, but Adobe is considering whether it might want to be bolder.

“We’re definitely going to measure the feedback here and see how the community feels about this,” said Sharad Mangalick, digital imaging product manager at Adobe.