Call them drones or multirotors or quadcopters or flying cameras, it doesn’t matter: As of December 21, 2015, the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is requesting anyone who wants to fly an unmanned aerial system (UAS) more than 0.55 pounds (250 grams) and less than 55 pounds (approximately 25 kilograms) for recreation or hobby to register with the agency.

The FAA is using the term UAS for anything piloted by a ground-control system, such as a radio controller. “Drones” may have sparked this move for registration, but it’s for pilots of all model aircraft — planes and helicopters included.

The new requirement stems from concerns that UAS pose new security and privacy challenges and that registration will give new users the opportunity to learn the airspace rules before they fly, reinforce the need for current pilots to operate their aircraft safely and develop a culture of accountability and responsibility.

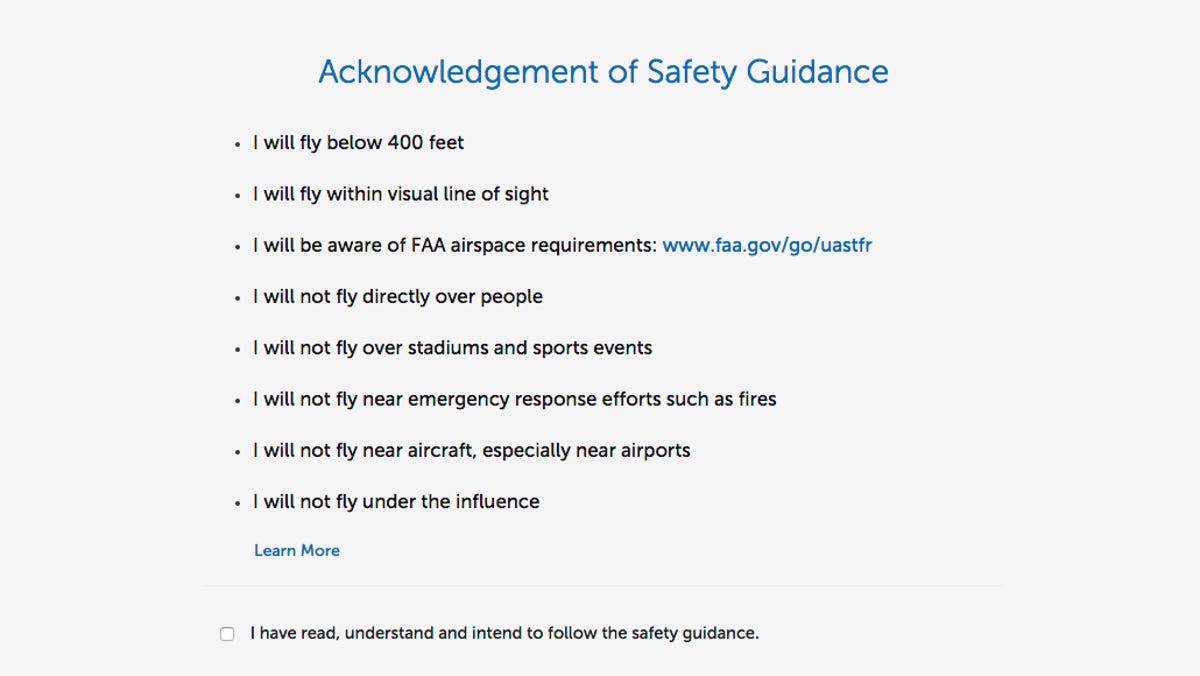

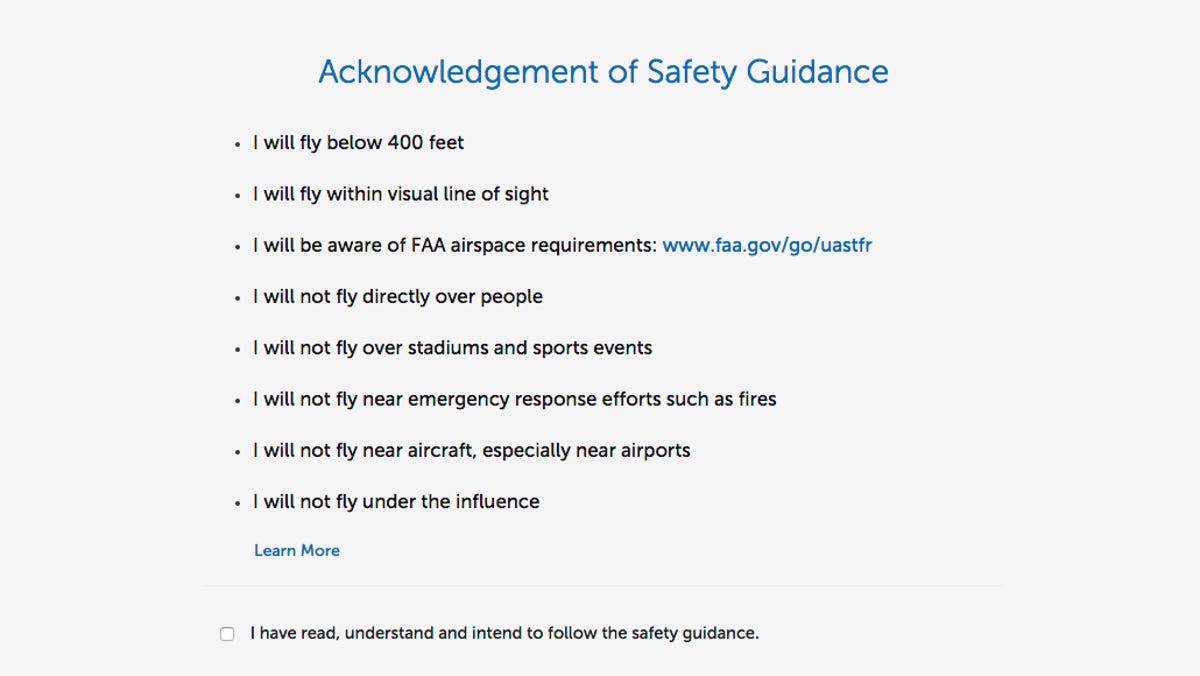

Basically, the FAA wants you to agree to a terms of service to fly in US airspace — anywhere from the ground up and whether you’re flying on public or private property. For RC hobbyists (read: noncommercial pilots), the FAA safety guidelines limit recreational use of model aircraft to below 400 feet, within sight of the operator and more than 5 miles away from airports and air traffic without prior FAA notification. These guidelines fall in line with the National Model Aircraft Safety Code of the Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA), the world’s largest model aviation association.

Screenshot by Joshua Goldman/CNET

The FAA says it has the authority to require this registration for modelers and hobbyists because federal law requires aircraft registration. The AMA, on the other hand, says “the registration process is in violation of Section 336 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (PDF), in which Congress states the FAA may not promulgate rules or regulations on model aircraft.”

The AMA was part of the FAA task force put together in October for developing UAS registration requirements and believes its more than 175,000 members should not need to register with the FAA. The association is currently recommending that members hold off on registering with the FAA until advised by the AMA or until the FAA’s legal deadline on February 19.

So, now what? Well, if you’ve flown a UAS prior to today and you want to follow the FAA rule, you have until that February 19 deadline to register. If you haven’t flown one yet, you must register before your first flight outdoors.

If you’re still not clear if you need to register that toy quadcopter you’ve been flying around your back yard, here is a breakdown of the FAA’s registration guidelines.

Small toy drones like the Air Hogs Millennium Falcon that weigh less than 8.8 ounces do not need to be registered.

Joshua Goldman/CNET

What needs to be registered:

If your UAS weighs more than 0.55 pounds (250 grams) and less than 55 pounds (approximately 25 kilograms) on takeoff and is being operated outdoors will need to register with the FAA. The control system can be remote or tethered, so if you’re using a UAS such as the Fotokite Phi and the total weight is more than 0.55 pounds, you’ll still need to register. If all you’re doing is flying indoors, you can skip the registration, but as soon as you head outside you’ll need to be registered.

Most sub-$100 UAS fall under this weight. For example, all of these toy drones weigh in under that half-pound mark. A kitchen or postal scale can be used to weigh your drone or you can check with the manufacturer. Also, this applies to both store-bought and homemade aircraft.

Who needs to register:

Individual recreational or hobby users 13 years of age or older who are US citizens. (Registration will serve as a certificate of ownership for non-citizens.) To register, you’ll need to give your complete name, physical address and mailing address if different, and an email address. The email address will be used as your log-in ID for your account.

Screenshot by Joshua Goldman/CNET

There is a $5 fee payable by credit card and you’ll need to renew it every three years and those will cost $5 as well. If you register by January 21, 2016, the $5 will be refunded. Why the fee in the first place? The FAA says it’s to cover costs of creating, maintaining and improving the registry system and helps authenticate the user.

Though the FAA’s site says “Register my drone,” you’re actually only registering yourself. When you register you’ll be given a unique number to mark on all your aircraft. (Here’s a PDF on how marking should be done.) This way, if you own multiple aircraft you only have to register once and, should you decide to sell your UAS, you can just remove your number. You’ll also need to keep a physical or electronic proof of registration on you when flying.

Screenshot by Joshua Goldman/CNET

Recreational pilots do not need to supply anything specific about their UAS to the FAA such as make or model. However, your registration information is linked to your registration number. Under the Privacy section of its FAQ, the FAA at first seems to say the information collected will only be visible by the agency and the contractor maintaining the database. That is followed by another section that suggests that names and addresses will be searchable by registration number.

According to Forbes, public searches of the drone registry system by registration number will be available. The reasoning is that UAS have a greater potential of flying off and should an aircraft land in your yard or pool or car, this would allow you to track the owner’s name and address, which, you know, sounds like an invitation for citizens to take matters into their own hands. The FAA does say you should call local law enforcement if an aircraft lands in your yard, but if that’s the case, why make the database searchable?

Screenshot by Sean Hollister/CNET

If you’re OK with trusting the FAA with your mailing and email addresses and your credit card information — and you have to be in order to register — the whole process is pretty painless. Well, assuming you can get the site to cooperate: It was running a little slowly when I registered earlier today, so if you’re experiencing delays try again another day.

What happens if I don’t register?

If you’ve been flying safely up until now, it would certainly be tempting to skip the registration process entirely. Just to get its point across, though, the FAA states that failing to register may result in civil penalties up to $27,500. Criminal penalties may include fines up to $250,000 and/or imprisonment for up to three years.

Chances are, if you’re a responsible hobbyist you’re not concerned with the criminal penalties. But a civil fine of up to $27,500 for flying a 10-ounce quadcopter unregistered — even in your own back yard — seems excessive to say the least.

There’s also the matter of registration really not solving the problem, which is careless or intentionally dangerous piloting. Again, this is the FAA’s attempt to make sure you understand there are basic rules to follow when flying any UAS. But anyone who makes the effort to register likely isn’t the problem and those really intent on doing harm won’t register.

Now, what are we going to do about registering those laser pointers?