The male peacock spider doesn’t have an extensive showreel. When you’re the size of a fingernail, it’s hard to command the attention of wildlife filmmakers — if camera crews haven’t spent years stepping over you in the undergrowth, then they haven’t had the gear required to capture your colours in glorious detail.

Compared to lightning-fast cheetahs or a pride of lions tearing apart its prey, a tiny spider is incredibly hard to shoot. While they present their own challenges, the savannahs of Africa are relatively easy to capture on film, and years of slinging gyroscopically-stabilised cameras onto helicopters has given us the footage to prove it.

But when the male peacock spider enters mating season, he performs one of the most colourful mating displays in the animal kingdom that puts the big cats of Africa to shame.

So when it comes to capturing the mating dance of such a small creature without it disappearing into the background, how does a wildlife photographer use their kit to capture a totally new story? The short answer is a very good macro lens. But the long answer behind this kind of technology is a rich history of film crews working on the frontier, hacking their camera gear to develop special custom equipment that is designed to meet the specific needs of wildlife photography.

Kitbashing

The filmmakers at Britain’s BBC network are old hands at kitbashing — the practice of modifying commercial gear by adding and removing parts to create custom equipment for a specific purpose. For the BBC’s latest wildlife series “Life Story,” the film crew developed a number of specialty camera rigs to meet the unique requirements of filming animals, just like the peacock spider, in their natural habitats.

“Life Story” stands apart from other documentaries, though not just in terms of scale. The crew captured 1,800 hours (or 300TB) of footage from 1,900 days in the field, lugging 23 tonnes of gear across 6 continents over a period of 4 years. This was all whittled down into six hours of documentary film, which has recently been released on DVD and Blu-Ray.

But in all that shooting, the team also sought to bring a new perspective to the animal kingdom, doing away with sweeping shots of gazelles leaping across the plains, and getting the lens into new, strange places to tell the stories of animals like audiences have never seen.

As the creative director of BBC Worldwide, Dr Mike Gunton is certainly well versed in traditional wildlife documentaries, but for “Life Story” the BBC was searching for something new.

“In ‘Life Story’… we wanted people to experience what it was like to be in the middle of the action and on the shoulder of the animal, no matter what they are doing,” Gunton told CNET.

For that new perspective, the crew jury-rigged surveillance cameras, tweaked lenses, built underwater rigs and customised cameras to get as close as possible to the action. In short, they kitbashed until they found a way to capture the previously “unseen stories” of nature.

“All these technical innovations, even these micro photographic innovations, can allow you to get yourself immersed in stories that would otherwise be impossible to see,” Gunton said.

Fish-eye view

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageBBC/Kat Brown

This approach led the team to develop Meercam, a sort of “steadycam turned upside down” for filming one of their life stories about a family of meerkats.

The upside-down design brought the lens of the video camera down to the meerkat’s eye level, skimming along six inches above the ground. At this level, a confrontation between a family of meerkats and an aggressive cobra takes on a whole new intensity. Not only does the audience see the animals in vivid Ultra HD detail, but they’re also in the centre of action, positioned in the centre of the pack both physically and emotionally.

The “Life Story” team also rigged commercial surveillance cameras into what Gunton calls “cam-balls” to capture the unseen lives of animals in close quarters. Rigged with remote controls, the cam-balls could stay in the centre of the action, leaving the crew to sit in the wings and capture the action without startling the wildlife.

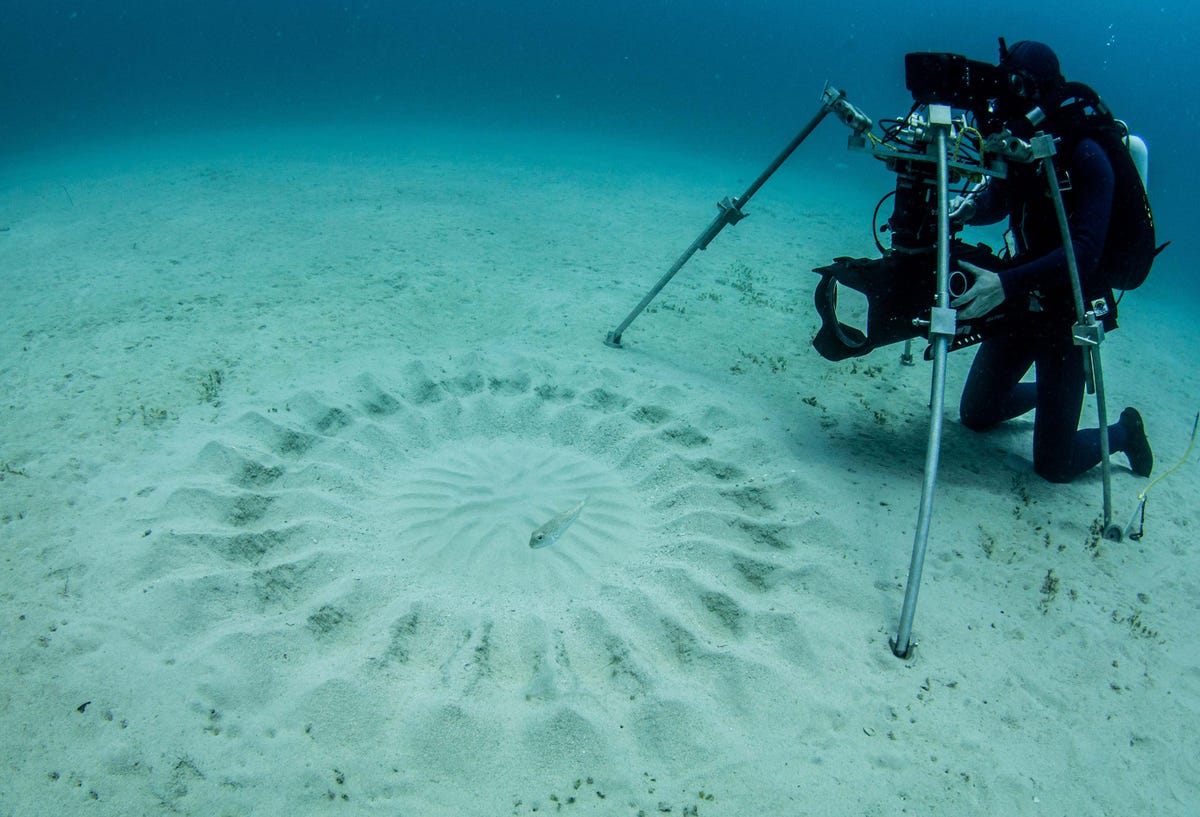

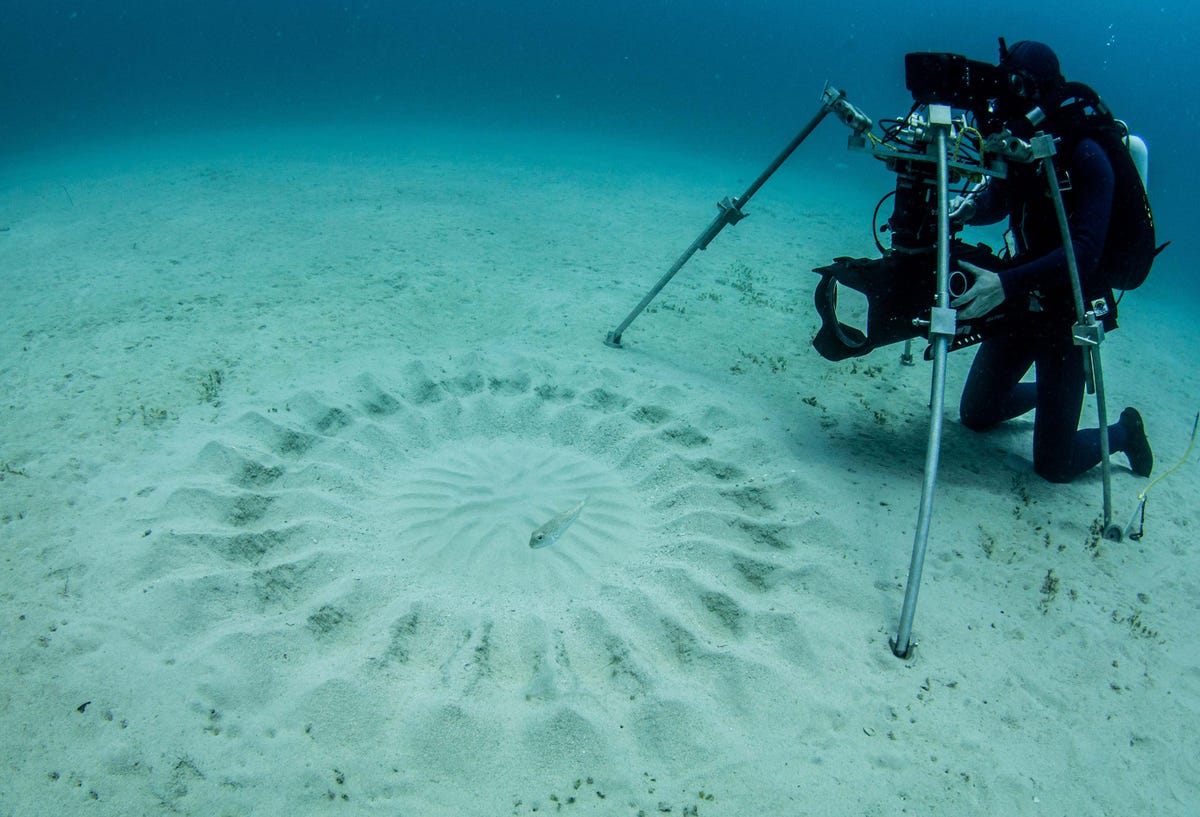

The crew was also able to shed light on a natural phenomenon that had taken on an almost mythic status in sci-fi circles: the unique ‘crop circle’ formations of sand made on the ocean floor by a specific breed of Japanese pufferfish.

Images of the circles had long circulated on the internet, but the “Life Story” team was able to take their crew to the floor of the ocean and capture the pufferfish creating this pattern in exquisite detail.

“The scale and detail of this was so extreme that we had to rethink how to film this underwater,” Gunton said. “Effectively, we had to build ourselves a kind of underwater studio with a camera that could be tracked around, so we could get down to pufferfish level and see it from fish-eye level as he built his structure. And finally had to build another structure so we could get an aerial view of the finished masterpiece.”

But the BBC’s intrepid team were by no means the first photographers to create quality images from hacked equipment. According to Gunton, the customised cameras of “Life Story” have a long history behind them.

Historic hacking

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageBBC/Sophie Darlington

After more than two decades at the BBC spent filming series such as “Galápagos” and “Life in the Undergrowth,” Gunton knows what it’s like to film in harsh environments. But he says a frontier mentality has actually helped wildlife photographers to stay at the forefront of advances in professional photography.

“We love hacking technology,” he said.

“Part of it is historic. The wildlife filmmaking community was much more disparate in the early days. People did just go and live in Africa for 20 years on their own thinking, ‘How am I going to film this?’ They were some very clever, inventive people and they were doing their own sort of home-built hacking.”

When the BBC’s photographers first set out to shoot tiny subjects such as insects and spiders, professional lens manufacturers weren’t tripping over themselves to spend a fortune creating macro lenses that only a limited group of filmmakers would use. So necessity became the mother of invention.

“They had to adapt what was existing,” Gunton said of the early wildlife filmmakers. “There were guys who were hiring a lathe, getting some aluminium tubing and experimenting with the length and putting mirrors in.”

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageBBC/Sophie Lanfear

The result was a sort of DIY macro lens that allowed filmmakers to get extra depth of field with very tiny objects, just like our friend the peacock spider.

“These were people building their own lenses from scratch. Often the reason why you hired a cameraman was because he had built that lens, he was the only person who had it. There was an incentive for them to do it.

“So there is this legacy or ethos of, ‘We’ve got a photographic challenge, let’s try and adapt, scrounge what there is and make something that will work for ourselves.’ Partly because there was nothing else and also partly because it gives you, if you’re the cameraman, a competitive edge.”

But it wasn’t just the very small creatures getting the attention, these filmmakers wanted to capture the very fast animals too.

Taking inspiration from crash test cameras used by car manufacturers, camera crews also developed their own ultra-high speed cameras to capture footage in slow motion — imagery that we now see as a visual staple of wildlife photography. From those early crude cameras, leading equipment manufacturers soon began to catch up and started building this kind of equipment on a commercial scale.

But while today’s camera crews might have access to better lenses and imaging technology than the BBC’s first filmmakers, that original ingenuity has not diminished.

The early filmmakers kitbashed in order to get a competitive advantage or simply to get the images they could see with the naked eye but couldn’t capture on film.

Now, photographers are hacking technology to take the lens to new places, getting a new perspective and telling new wildlife stories that a doco-weary audience has never seen before. We’ve soared with helicopters over the savannah, but now wildlife lovers can peer over the shoulder of a cobra, run alongside a cheetah, get a fish-eye view on the ocean floor, and even watch the mating dance of a tiny arachnid Casanova from the edge of the branch.

“Innovative technology has always been part of natural history,” Gunton says. “And innovation can’t stop. You have to keep going. You have to be continuously searching for new technology, new techniques, new ways of telling the story, and new platforms, all to show as large and as wide-ranging an audience as possible the wonders of the natural world.”