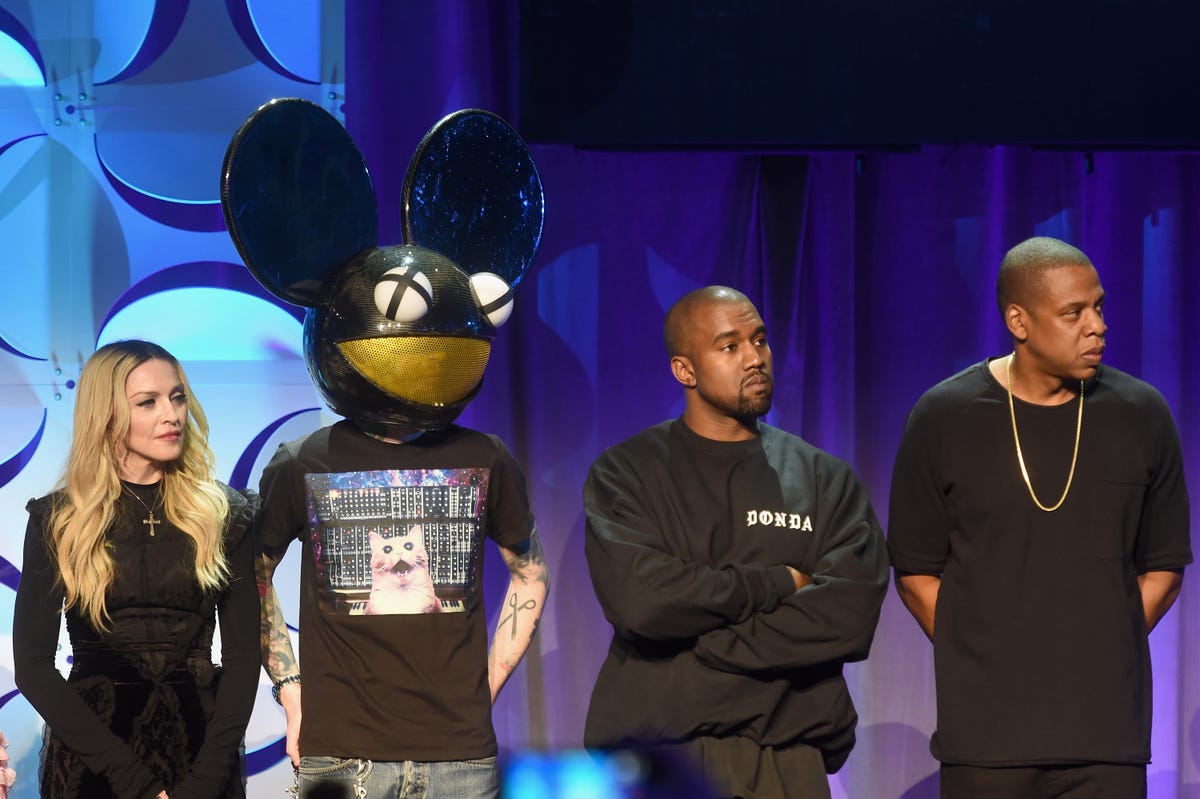

Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images for Roc Nation

Is Tidal, the music-streaming service headed by hip-hop mogul Jay Z, the end — or is it the beginning? After a glitzy launch in March, Tidal has a horde of detractors baying for its blood. It’s already been deemed a failure, despite offering the possibility of exclusive albums from high-profile artists like Beyoncé.

As a newcomer, it’s difficult to expect Tidal to overcome the mighty incumbent Spotify in the first few months of its life. Sure, it hasn’t motivated millions of Spotify subscribers to suddenly jump ship and start paying for subscriptions, but this is not Tidal’s fault. I believe it’s a problem with our perception of how music should be consumed: why pay for it when we can get it for free?

Until the rise of the Internet in the ’90s, it was actually quite difficult to pirate music. Remember Home Taping is Killing Music? Laughable by today’s standards. Sure, you could make mix tapes and give them to your friends, but there wasn’t the ability to find anything you wanted instantly. Bootlegs of live concerts were a thing, and they were sold at flea markets or on blankets, but the law mostly looked unkindly on these — and you still had to pay money.

Ingrid Marson/CNET UK

No, it wasn’t until Napster started up in 1999 that this current thinking got a foothold. The free software made peer-to-peer swapping of music files dead simple. Here at last was the world’s repository of music — albeit in terrible quality — and you didn’t have to pay a dime! While the original Napster was finally shut down in 2001, the “music should be free” ideology spread to other services: the likes of Kazaa, LimeWire, and — finally — BitTorrent. While numerous attempts have been made to legitimize music sharing on BitTorrent, a 2010 study by the University of Ballarat has suggested that only 0.3 percent of torrents are legal.

To date I have not seen one cogent argument about why music should be free. Because it’s easy to pirate? Sure. So are movies. So is TV. Despite BitTorrent’s ubiquity, people will still happily go to the movies or pay for a Hulu subscription.

Most households in the United States pay for a cable or satellite TV subscription, but why would they if pirating is so easy? Because if you give people what they want and when they want it, people will pay for it. But if you also offer them the same content for free — as is the case with Spotify — why would they bother paying?

Spotify, Pandora and YouTube: Free music 2.0

To be clear, Spotify is not pirating music. The streaming service has deals with all the major record labels, and it has a paid subscription service that lets you download playlists to smartphones and stream to a wide variety of devices. But it also offers a “freemium” option that delivers a slightly restricted version: no downloadable playlists, limited song skips and the inclusion of ads.

In that sense, Spotify’s free service is similar to Pandora. Or iTunes

Radio. Or Songza. Or Slacker. Or YouTube (which is huge global showcase for free music). But even though all of these “radio” services are aboveboard, they’re keeping afloat a false expectation that music should continue to be free.

Despite my own personal preference for buying whole albums digitally and on vinyl, I am not afraid of streaming and really believe it has a future. It’s at this point I should disclose I am a paying subscriber of both Tidal and Spotify, and use each service often. But as one of the 15 million paying Spotify subscribers, I am still in the minority of over 60 million active Spotify users. In its seven years in existence Spotify hasn’t been able to see a profit yet, much less pay the artists what they’re worth. It’s nine months since Taylor Swift first made a stand, but things still need to change.

Related

- Jay Z splashes out $56 million on Spotify rivals WiMP and Tidal

- Jay Z’s Tidal music service makes star-studded splash

- Taylor Swift is right about music, wrong about Spotify, says CEO Ek

- Streaming music swiping sales from music downloads

- Spotify closes in on $8.4 billion valuation with latest deal

The current streaming model is a good start, but it is horribly broken. I support recording artists (successful or not) when they say the only way forward is if all subscribers pay a fee.

Think this sounds unfair? No one expects Netflix — with its rotating roster of movies and TV shows — to offer a free model. It’s because Netflix doesn’t that it can afford to fund excellent programming such as “Orange Is the New Black,” “House of Cards” and “Daredevil.”

In my conversation with former Tidal CEO Andy Chen in December 2014, he told me that by charging $20 for its service — and offering higher-quality lossless music in return — the company was able to give more back to the artist. He was completely of the belief that “Music should not be free. People should pay.” He told me that as Tidal is privately owned, it could exist as a boutique service that wasn’t subject to the pressures of a public company. Presumably, Jay Z — who took the reins earlier this year — thought some change was in order by instituting a $10 option, and subsequently Chen was gone. But crucially, despite the changes, Tidal still charges for each subscription.

Spotify’s CEO, Daniel Ek, made some salient points back in November when he was responding to Taylor Swift — most notably, that “more than 80 percent of [Spotify’s] subscribers started as free users.” But the company’s current strategy of massive subscriber growth — most of which subscribers are entering the free advertising-funded tier — seems untenable over the long term. What happens when the growth curve flattens, and Spotify fails to attract new subscribers? To quote John Steinbeck’s novel “The Grapes of Wrath”: “When the monster stops growing, it dies. It can’t stay one size.” It’s the default business model in our postmodern age: to keep expanding the company and never stop. But as Steinbeck saw back in the 1930s, it ends up hurting the little guy, and in our particular case, that’s the musician.

Screenshot by Ty Pendlebury/CNET

A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work

One of the biggest fallacies about the music industry, and one used especially when trying to justify low streaming payouts, is that musicians make money from touring. Yes, mega-acts like the Rolling Stones, Katy Perry, Lady Gaga — and, indeed, even Jay Z and superstar spouse Beyoncé — can gross tens of millions of dollars on the road, but many musicians touring today are lucky if they make enough to pay for the tour itself before going back to their day jobs, or unemployment. When you add the cost of making and distributing an album to “promote” these tours, it becomes a very costly “hobby.” Music was already a tough industry for many people to make money in, and streaming is currently making it tougher.

If an artist or an artist’s record company paid money to have a record made, it makes sense that they deserve some recompense. While record companies appear happy with the current system, it seems that every day we see a story about how pitiful the payouts to artists are. In April, Portishead guitarist Geoff Barrow said he received £1,700, about $2,500, for 34 million streams on Spotify.

Despite such poor payouts, it’s still possible to make money on the Internet — if you make videos, that is. For example, YouTube celebrity PewDiePie rakes in $4 million a year from his gaming videos, and he only needs a webcam and an Internet connection. Compare this with the comparatively high overhead of a touring band — string sections, record production and tour buses — and it’s clear that streaming audio is not up to the level of profitability that video offers yet. But as many young people listen to music on YouTube there is definitely an opportunity for artists to control their revenue via the video-streaming site.

But what of Spotify’s mantra of “growth equals profit”? Jon Maples, the former vice president of Product and Content for Rhapsody, wrote that an increase in growth doesn’t necessarily equal an increase in revenue, but does equal an increase in costs. He claims that with Spotify’s current model, it is the small number of paying subscribers who end up paying for the nonpaid users, as he says advertising revenues are so low. While CEO Daniel Ek argues Spotify pays for every play on its service — whether it’s on a paid or free subscription — he carefully words this so that it isn’t apparent where the money that pays for it comes from. If Spotify is getting more subscriptions without focusing solely on paid subscribers, it means this lopsided situation will continue.

Ty Pendlebury/CNET

Granted, Spotify has made some good headway in the past few months with an uptick of 2.5 million paid subscribers (for a total of 15 million, up from 12.5 million). This is thanks in part to a 99-cents-for-three-months promotion and the longer-term — and much-needed — addition of a $4.99 family member option. Music industry site Music Ally claims this means Spotify is now ahead of competitor Rhapsody in total number of paid subscribers. But can Spotify hold on to its 15 million subscriptions without having to dangle further carrots, or will people simply go back to the unpaid option?

In that same November response to Taylor Swift, Ek pointed out that Spotify had paid out $2 billion to “labels, publishers and collecting societies” since 2008, with half of that in 2014 alone. It’s an impressive figure, but notice that Ek didn’t say how much was actually paid to artists? (Admittedly, the issue of record labels’ relative value to artists — or lack thereof — is a whole separate discussion best saved for another time.)

The fact is that music revenues are on a downward slide, with the industry making half of the money in 2014 that it did in 2002– a decline from $30 billion to $15 billion. Even with some of those $15 billion coming from Spotify, it appears there is a long way to go to make up the shortfall. Even if we believe the Credit Suisse projection that music revenue will begin inching up — and that streaming royalties will make up the majority of music industry revenue by 2017 — it’s worth noting that overall revenue projections still stay short of $18 billion, or a little more than half of that 2002 peak.

Funnily enough, Netflix has almost 60 million subscribers as well (but they’re all paid), and yet apart from the differences in content, Netflix also offers a less comprehensive deal: a rotating list of movies and TV shows that fold in and out every month. I’m not suggesting Spotify should take up a similar rotational model — the company’s ambition to stream “all the world’s music” is one of its greatest assets — but it just shows that people are willing to put up with something less than an all-you-can-eat model for video services and yet still pay for them.

What is the way forward? Well, that path may well rest with Mr. Daniel Ek, CEO of Spotify.

Mr. Ek, I believe it is now up to you. Please. Get rid of nonpaid subscriptions. Yes, you will probably lose a huge number of subscribers, but it will make a definitive statement to all of the “freemium” services that a user-pays system is the only way to sustain a music industry.

It’s worked for Netflix. It can work for music, too.