Bob Maresca had just returned from a product launch event in New York when he got the call. His boss and mentor, 83-year-old Amar Bose, had been rushed to Lahey Hospital in Burlington, Massachusetts, and they didn’t know whether he’d make it through the night.

When Maresca got to the hospital, he found Vanu Bose sitting with his ailing father, whom everyone called Dr. Bose. The founder was unfamiliar with the products Maresca’s team had introduced to the press that day, the SoundLink Mini wireless speaker and QC20 in-ear noise-canceling headphones. After hearing Maresca’s enthusiastic description of the event, Dr. Bose said he wanted to see them.

Maresca wasn’t quite sure how serious he was, but he promised to return at 6 a.m. to give him a demo, silently worrying it would be too late.

Enlarge Image

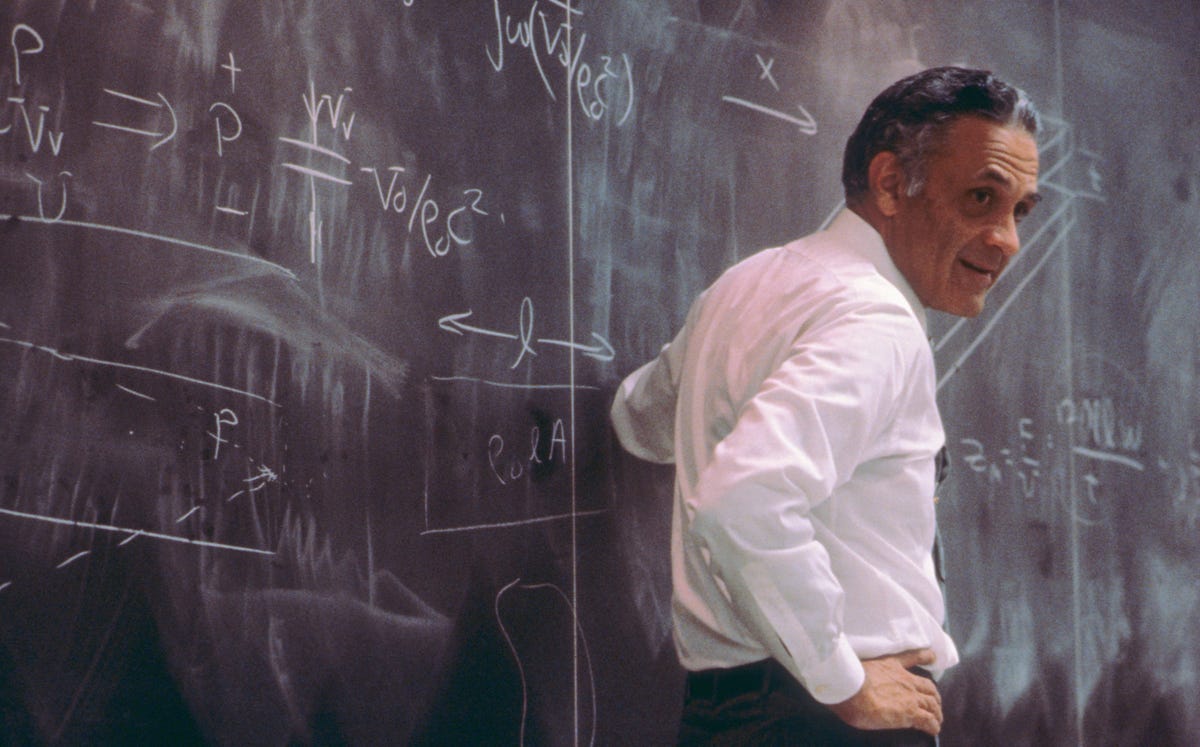

Enlarge ImageBose’s founder Amar Bose teaching at MIT.

Bose

The next morning the two younger men arrived at the hospital just hours before Bose died. Maresca brought with him a SoundLink Mini, a QC20 and an iPhone loaded with Bose’s favorite music.

“He was just blown away with where the state of noise cancellation had come. He just had a huge smile on his face,” Maresca says of his old professor’s response to listening to the new headphones.

Maresca then pulled the tiny SoundLink Mini from his pocket, placed it on the bed, and the sound of Yo-Yo Ma playing Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites filled the room.

“I watched him enjoy that music, and he was fulfilled. He was so, so happy and so proud of his company, that we could create a product like this.”

The company that created those products has long been considered guarded, insular and secretive. Its charismatic and intensely private founder reflected his company’s personality, instilling a sense of superiority and ambition in its culture. He had a sign on his desk that said, “If you think something is impossible, don’t disturb the person who is doing it!”

Until recently, it’s a company that has shunned publicity. Indeed, not many reporters have ventured to Framingham, Massachusetts, the headquarters of Bose Corporation. One of the most recognized audio brands in the world, not a lot is known about what happens here and why. But today, I’m getting a rare tour and the opportunity to see what goes on behind closed doors.

Many don’t even know that the company was founded by Bose, who started in 1964 making speakers with designs he’d patented. Before he died on July 12, 2013, he’d put his most trusted lieutenant in charge.

Bob Maresca, Bose’s current CEO and president, is no Silicon Valley wunderkind. He’s an MIT grad, like Bose, who’s worked for the company for nearly 30 years. But Maresca is also Brooklyn-born and bred, and a former construction worker, giving him a perspective on a luxury brand that’s increasingly rare.

Like some notable Silicon Valley CEOs, Maresca does things a little differently. He has to. The consumer electronics market has evolved radically in both the marketing and sales of products and how quickly competitors release new ones.

Privately held, Bose has had the freedom to develop new products and innovate at its own steady pace, plowing its profits back into research, without having Wall Street investors breathing down its neck. But due to the new dynamics of the 21st-century electronics market, the company is under pressure to innovate faster than it once did.

Chief among those new challenges is Apple. The tech giant is a classic corporate frenemy: it’s both a retail partner for Bose (its products are sold online and at brick-and-mortar Apple Stores) and one of Bose’s main competitors, thanks to Apple’s $3 billion acquisition in 2014 of Beats, the trendy headphone brand founded by musician Dr. Dre. And, while Apple declined to comment for this article, research firm NPD pegs Beats as the top brand for headphones in the US, garnering almost one in three dollars spent on headphones in 2015. Bose was number two, with 11 percent of the revenue in the category — about a third that of Beats.

NPD analyst Ben Arnold doesn’t see Bose and Beats competing for the same consumers, particularly “fickle millennial buyers” because being cool “isn’t a staple of Bose’s brand like it is for Beats.”

That said, even non-Beats consumers want Beats-like features such as colors, forward-looking designs and celebrity and athlete endorsements, Arnold says. “Bose’s challenge is satisfying consumer demand for things that aren’t necessarily tied to ‘better sound through research’ but that still stay true to their brand and keep their die-hard buyers engaged,” he adds.

As Bose navigates that tricky cross-generational appeal, the company is honing its image — not to become cooler but to become more “relevant,” which is partially code for being included in the social-media conversation.

At the same time, Maresca isn’t straying from the basics: “Our goal is to make products that people love.”

The reluctant CEO

Maresca never wanted the job of chief executive. He claims he wasn’t qualified for the position — or any of the previous executive positions he’s held during a career which has included stints as head of Bose’s Noise Reduction Technology and Home Entertainment groups.

He says he fought hard against his appointment to president in 2005. “I wasn’t qualified for the other two jobs, and I definitely wasn’t qualified to be president of the company.” Now he is a reluctant CEO.

Maresca, who goes by Bob, tells me all this as we drive in his Audi sedan from Framingham to Cambridge to meet the MIT Provost and speak to the winner of a Bose research grant.

Despite his gray, thinning hair, Maresca’s trim build and confident, boyish smile make him look younger than his 60 years. Carolyn Cinotti, Bose’s Head of Global PR, silently follows our conversation from the back seat, resigned to the possibility her boss won’t always stay on message. “Bob’s just Bob,” she told me earlier. “He’s unscripted.”

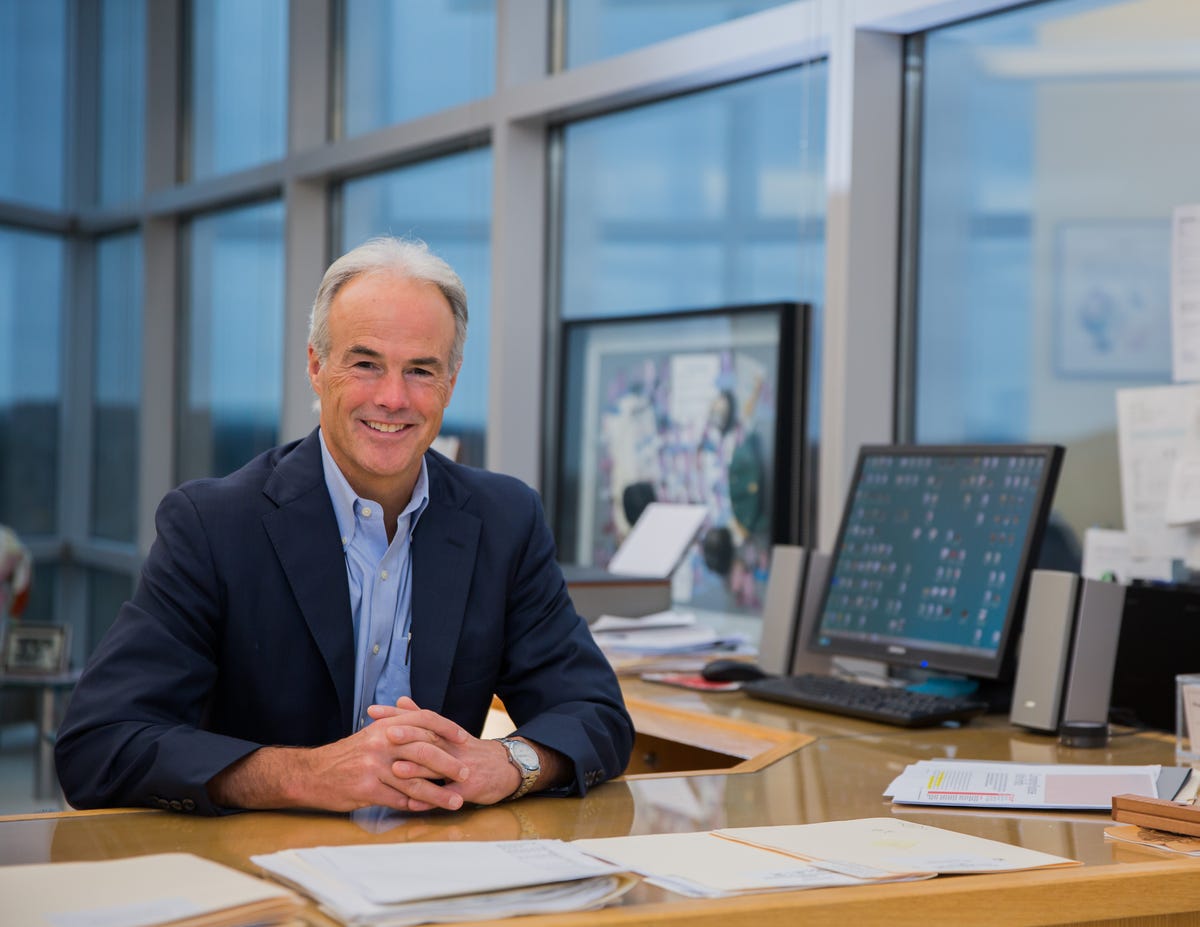

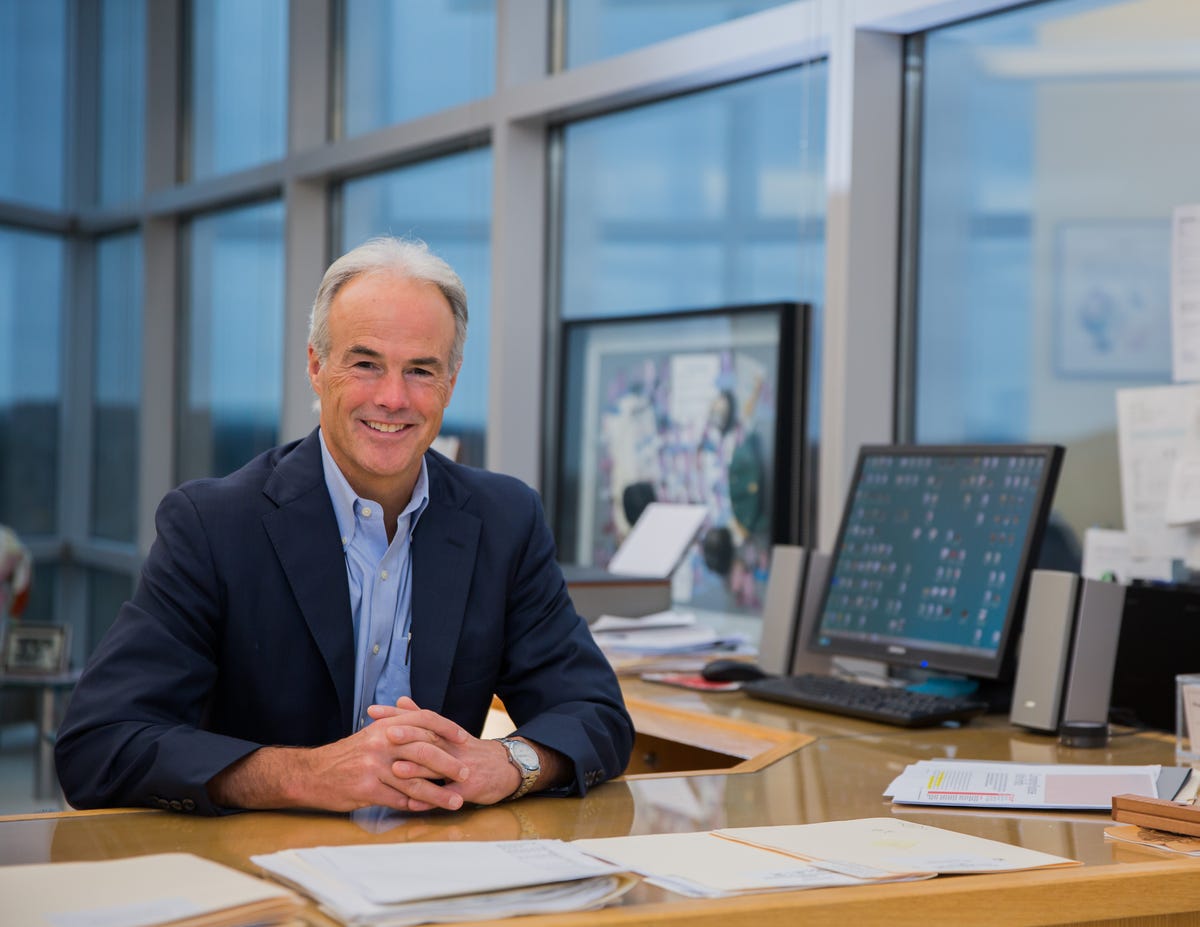

Enlarge Image

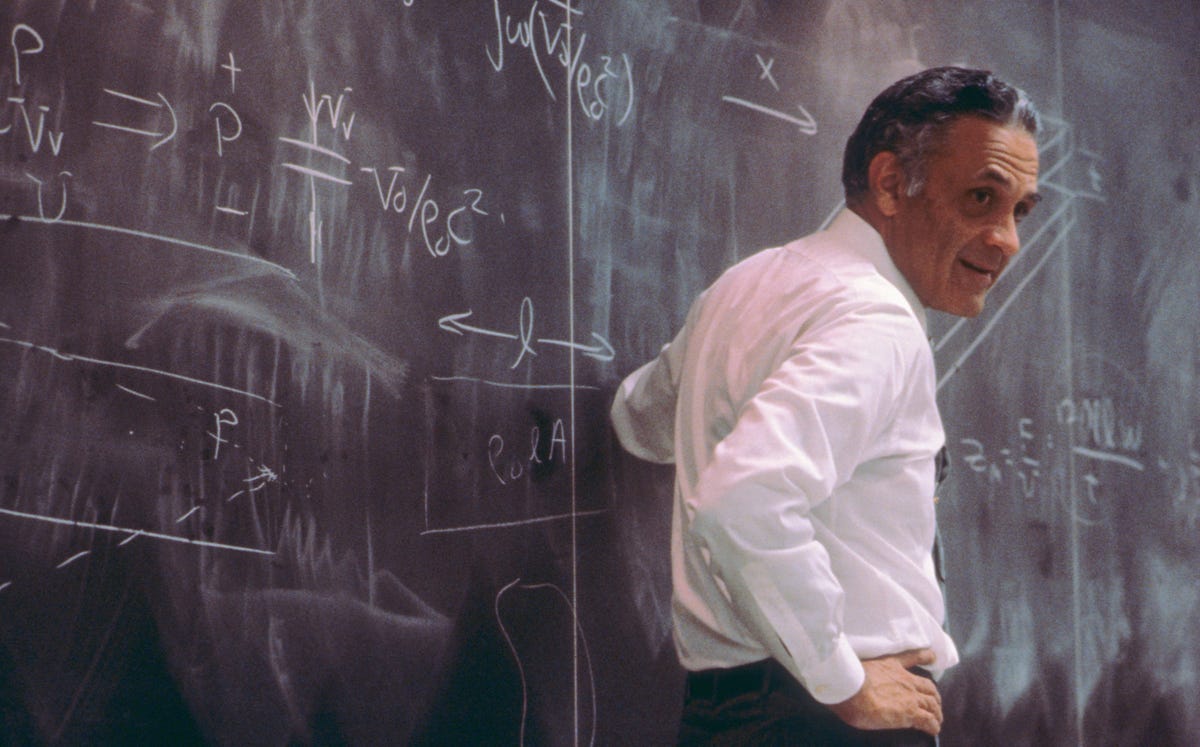

Enlarge ImageBob Maresca, Bose’s president since 2005, assumed the CEO position after company founder Amar Bose died in 2013.

Sarah Tew/CNET

So if he didn’t want the president’s job, why’d he take it?

“You know,” he says, “I owe Dr. Bose so much and I respect him so much that I would do anything for him. I was hoping to someday get back to research but that plan doesn’t look like it’s going to happen.”

Earlier, I noticed Cinotti tearing up a little up while we were watching a 2011 tribute video celebrating Bose gifting the company to MIT.

No, that’s not a misprint. Bose, longtime MIT professor and member of the class of 1951, quietly transferred his stake in the company to his alma mater two years before his death. Not a word about it from the Bose Corporation. A brief press release from MIT. Yet Bose had given to MIT the majority of the stock of Bose Corporation, albeit in the form of non-voting shares.

Under the terms of the gift, the university receives annual cash dividends on those shares. MIT will use those dividends, the value of which is unclear, to “sustain and advance MIT’s education and research mission.” MIT cannot sell its Bose shares or participate in the management or governance of the company, which remains privately held.

Talk about self-effacement. Bose wanted no publicity about his gift, so his corporate communications team turned away all press inquiries. They also never publicized Maresca’s appointment to CEO in 2013. I only found out about it several months after the fact. “Oh, no, I guess we didn’t [put out a press release],” Cinotti told me. “It’s not really our way.”

Now playing:

Watch this:

Inside Bose’s top-secret testing lab

2:49

Pivot point

Bose Corporation hasn’t always played nice. In 1971, Consumer Reports published a critical review of the company’s controversial breakout product, the 901 speaker. The 901 incorporated a patented arrangement of nine small drivers that produced a combination of forward-firing direct sound and sound that reflected off the walls of a room, mimicking the way it travels to the ear during a live performance. The 901 produced a sound completely unlike that of traditional stereo speakers.

According to legal briefs, Bose himself felt the review wrongly described the speakers’ sound. Another point of contention was the writer’s inclusion of a small but important discrepancy from the test engineer’s report.

Bose demanded a retraction and didn’t get one, so it filed a product disparagement lawsuit against the magazine.

The case went all the way to the US Supreme Court. Ultimately, the issue was not whether Consumer Reports had made a mistake in its review, but whether it had done so maliciously. In 1984, the Court decided against Bose, 6-3.

The lawsuit didn’t harm business. Now in its sixth generation, the 901 remains on the market, and Bose takes in $3.5 billion annually. (Because it’s not a publicly traded company, the numbers it reports are scant, but Maresca says Bose is now “serving” 10 times more customers than it did in the early 2000s, many of them new to Bose, and an estimated 60 percent of them millennials.)

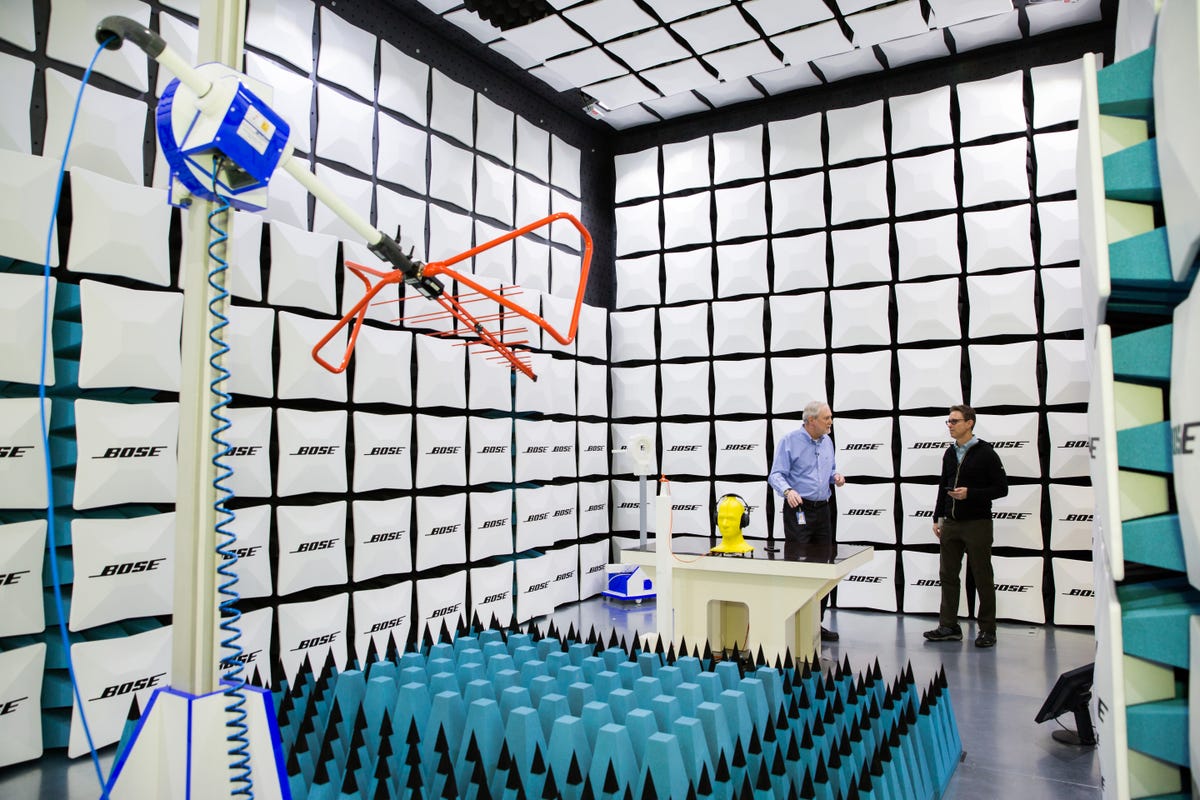

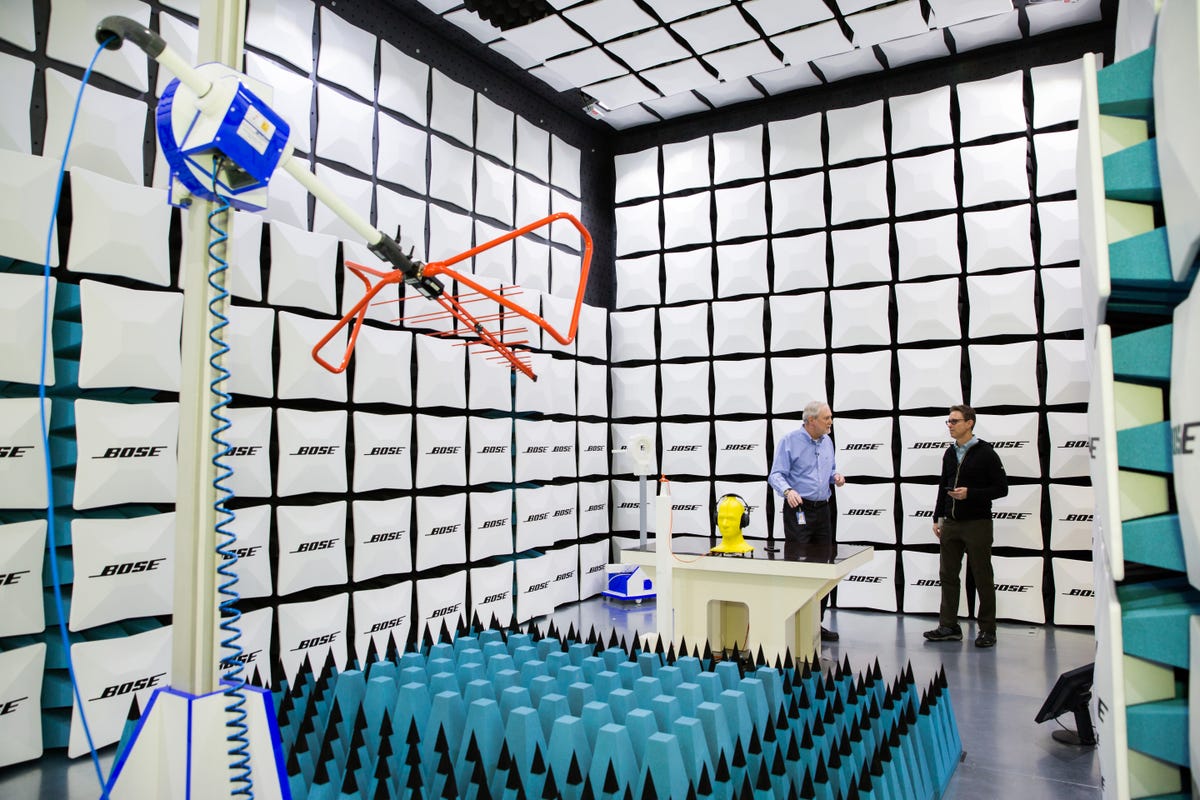

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageA 3-meter anechoic chamber for performing full compliance radiated emissions testing (and other tests).

Sarah Tew/CNET

Among the then-small world of consumer electronics reporters and the audio enthusiast press, however, the lawsuit — understandably — left a bad taste in people’s mouths. Even more recently, when I first started covering Bose products 15 years ago, a few veteran editors and writers still hesitated to review its products.

Recently, though, Bose has lowered its defensive shield. Maresca understands that audio is a subjective experience. “Everybody hears things differently,” he says. “You can’t have thin skin” about product reviews.

Little by little, post-Bose Bose is changing. Maresca also understands that the gift to MIT shouldn’t be kept quiet. While his boss and mentor was still alive, Maresca wasn’t allowed to discuss it. But he recently concluded that it reflects positively on the company and Bose’s legacy.

The company was changing and innovating before Dr. Bose died — though he remained Chairman and CEO he hadn’t been to the office since 2010 — but his death marked what can be seen as a pivot point that helped accelerate change.

Under Maresca, Bose has seen a near complete overhaul of its consumer audio line: headphones and speakers with Bluetooth (SoundLink) or Wi-Fi (SoundTouch) are now at the forefront of Bose’s offerings. Its products still aren’t cheap, but it is offering more products at more affordable prices.

“I think we can all agree that the pace of change is greater than it’s ever been,” Maresca says, “and it requires all companies to be faster and more agile.”

I’d seen lots of people sweating the details of industrial design relevance, ensuring product reliability and performance. But the goal, he told me, was not to be cool. At heart, he’s still an engineer.

Not just audio products

I’d spent the day meeting with Maresca’s lieutenants, many of whom, like him, began as engineers and continue to be crucial to the research and development of future products. To its credit, Bose wanted to make my visit interesting. They also want the world to know that they make more than audio products, even if its tagline remains, “Better sound through research.”

One of the highlights of my visit was a demo in the company’s parking lot of the product Maresca came to Bose to work on in 1986, an electromagnetic car suspension system that Bose thought would revolutionize the auto industry, but which eventually proved too costly and heavy to commercially produce. And then there was Senior Research Engineer Ken Jacob producing the perfect crepe, without throwing the first one away, on a high-tech induction stove, an upcoming project he’s worked on for 10 years.

Watch: Hands-on with Bose’s new super high-tech cooking system

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageSenior Research Engineer Ken Jacob with Project Vortex, Bose’s upcoming patented cooking system.

Sarah Tew/CNET

Back in the car I ask Maresca, a former high-school athlete, about Bose’s use of celebrities, and sports celebrities in particular, with new ads and a series of Better Never Quits videos on YouTube. Though presently limited to eight NFL players, including Seattle Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson, Houston Texans defensive end J.J. Watt and Arizona Cardinals wide receiver Larry Fitzgerald, one NFL coach (the Indianapolis Colts’ Chuck Pagano), and pro golfer Rory McIlroy, celebrity marketing seems very un-Bose like.

“Exactly,” Maresca says. “Because we had that direct marketing engine for so many years, we didn’t need celebrities.”

He’s referring to all those full-page ads — mostly for Wave Radio — that blitzed printed media in the US from 1993 to 2010. The campaign made Bose a household name, while also turning it into the Wave Radio company.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageBose doesn’t say its portable Bluetooth speakers are water-resistant, but judging from this rain test the speakers undergo, they are.

Sarah Tew/CNET

Selling directly to consumers — Bose took the orders and shipped the products — allowed the company to create the margins that paid for advertising. “We never had that marketing budget when we sold indirect,” Maresca says.

He didn’t have a hand in creating the Wave Radio but he became very familiar with profit margins after Bose assigned him to fix the company’s Noise Reduction Technology Group (NRTG) in 1997. The group was hemorrhaging money, selling aviation and military headsets for $1,000 when they cost the company $1,100 to make. “We were including a $100 bill with every purchase and people didn’t know it,” he says.

Things have changed. Bose makes money on its specialty aviation and military headsets (as well as other non-consumer products from its Professional Systems and Automotive Systems groups) and does quite well with its consumer noise-canceling headphones — in many ways they’ve become the company’s signature products. But the bulk of its marketing is now digital. It’s also a major presence in retail outlets, including those aforementioned Apple Stores, even after it sued Apple in 2014 in a patent dispute over Beats’ noise-canceling technology. (The two companies quickly came to a settlement, the terms of which were never revealed.)

“We’re experimenting with lots of different ways to reach these new customers,” Maresca says. “Celebrities is one way. Some ways work, some don’t. We are innovating in ways to measure the effectiveness of celebrities,” he adds without disclosing what those innovations are.

That’s entertainment

I ask Maresca about the perception among some people that Bose’s lightweight headphones are both cheaply made and overpriced. He agrees that there’s some subjective correlation between weight and expense, but, he argues, the company’s major focus has been comfort.

“So if we can get lighter, we will. Now if it’s so light that it’s not stable on your head, that’s a drawback. But we’ll always go lighter and smaller if we can. We’ll use a glass-infused aerospace plastic to get the ruggedness and still get the lightweight. In some cases — our aviation headset, for instance — we went with magnesium on the headband. It costs more but it’s high-strength, lightweight.”

The problem, I point out, is most people don’t know the difference between plastics. They have no idea Bose uses aerospace-grade plastic for their headphones.

He readily admits their lack of effectiveness in communicating that point. “We used to have a forum with our copy-heavy direct marketing ads and people read it. But people don’t read anymore so we’re struggling with this new way of short attention spans, how to get people to actually listen.”

It’s all about entertainment now, the firms creating their new ads say. That’s not something the engineering mind understands, Maresca says.

“You look at some of our ads with the NFL — we never would’ve done that in the past,” he explains. “It’s a 30-second ad that spends 23 seconds entertaining and 7 seconds discussing the product. We would never do that in the past because the engineering mind would say you just wasted 23 seconds not talking about the product. We’re learning to think more with the other side of our brains.”

Like an NFL team, Bose vets its athletes before it drafts them. Patriots quarterback Tom Brady didn’t make the cut, even though Marecsa, once a die-hard New York Giants supporter, is now a huge Patriots fan.

“There’s a business component here where you do the profile and you see the player’s social media activity, their favorability rating, the negativity rating –“

It’s no secret that Brady has some high negatives outside New England.

Cinotti, in a rare interjection, says she wants be clear that they’re picking athletes who share the company’s values. What a player does off the field is just as important as what he or she does on it.

During the 2015 Super Bowl, after Wilson threw an interception that cost Seattle the win against New England, Maresca sent him a text.

“My heart went out to Russell because I know what it’s like to let down your team with a mistake. And that’s what I told him. I’ve been there as a CEO of a company. I made a mistake. You don’t worry about yourself, you worry about all the other people that were counting on you. He texted back [from a Children’s Hospital, visiting kids with cancer]: ‘That’s exactly right. You know exactly how I feel.’ He’s a special person. He may not be the best quarterback in the NFL, but nobody is going to work harder.”

Maresca doesn’t make many mistakes. One of the throws he would take back, he tells me, is the premature release of the company’s first in-ear headphone. Having rushed production to get to market in time for the holiday season, the eartips had one flaw: they weren’t adequately secured to the bud and kept falling off. Bose eventually fixed the problem and offered consumers replacement tips. Still, Maresca says, “It was a disaster. We’ll never rush out anything again.”

Origin stories

Like other iconic — if better known tech entrepreneurs — Dr. Bose has an origin story. Not the proverbial startup in a garage narrative, but it has some American Dream elements. The short version goes something like this:

Amar Gopal Bose was born in Philadelphia to an Indian father and American mother. As a child Amar was a tinkerer. He fixed radios to help support his family. His father always told people Amar would go to MIT, which was exactly where he ended up.

After earning his doctorate — also at MIT — he rewarded himself with a set of new loudspeakers, which he bought based on what, according to his research, he believed to be the perfect specs. But the quality of the sound he heard through those speakers disappointed him so much that he soon found himself in an MIT acoustics lab trying to figure out why. Call it a bad case of buyer’s remorse, but the experience turned him on to the psychoacoustics of sound, which became one of the foundations of his company, as well as his teaching career at MIT, where he taught a best-in-class acoustics course, among others. That class eventually became a perennial favorite among undergraduates.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageMaresca says Bose, with whom he worked for 27 years, didn’t pass the torch to him but “shared it,” especially in the last 10 years of his life.

Sarah Tew/CNET

Maresca’s origin story, typical of Bose’s early employees and executives, also runs through MIT. But Maresca’s path there was more circuitous. He grew up the second of seven kids in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, a working-class Italian neighborhood best known for being the location of the movie “Saturday Night Fever.” His uncles taught him all about the construction trade: plumbing, heating, electric and carpentry.

“As a kid, every house we moved into needed work,” he says. So his grandfather would fix it up for his mom, with help from her brothers. His father never finished college but picked up a law degree at night from Brooklyn Law School.

Thanks to a scholarship, Maresca attended Poly Prep, a private school not far from his home in Brooklyn known for its rigorous academics and excellent sports programs. He was the quarterback of his high school football team and president of his senior class. He continued to play football during his freshman year at Williams College, an elite liberal arts school in Western Massachusetts. His tenure there lasted only a year; after one season playing Division III he realized he’d never make it to the NFL.

“While I was a good student, I didn’t see any reason to go to college,” he told me. “I just thought I’d go off on my own and make some money.” He quit school and began working construction with his uncles.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageMaresca outside of Bose HQ with Sherwin Greenblatt, the company’s first employee and former CEO.

Sarah Tew/CNET

That went well, for a while. He was making $7 an hour and had his own apartment in Brooklyn. But come winter, working on the 50th floor of a construction site on the east side of Manhattan, the charm of the job wore off. One of his mother’s brothers, who’d gone to MIT on the G.I. Bill, told him to go back to school at MIT. He could always go back to construction after graduation. Maresca refused to listen when his father called him an idiot for leaving school, but he listened to his uncle.

Maresca had been the top student in his freshman class at Williams. When he informed the school of his decision not to continue they were shocked. He had no trouble transferring to MIT, where he majored in mechanical engineering, but eventually fell for electrical engineering. During his junior year he began auditing “double e” classes. That’s when he found Professor Bose. He was hooked after auditing one lecture.

Fast forward a few years to 1980. Bose tried to recruit Maresca, who was fresh off a master’s in electrical engineering from Stanford. Maresca passed on the offer; at the time Bose was working on passive speakers, which didn’t interest Maresca. He was into electronics, control systems, magnetics and other stuff he thought was a lot cooler.

He took a job at Philips Research Labs in Briarcliff Manor, New York. There he worked on magnetically suspended coolers for infrared detectors that were used in space applications. They were essentially pistons that had no wear because there was no friction.

Now playing:

Watch this:

Watch Bose’s incredible electromagnetic car suspension…

2:19

Bose didn’t give up. In 1986, he asked Maresca to work on a special project: an electromagnetic car-suspension system that would come to be known as Project Sound. The idea was to invent a system that anticipated and rose above bumps in the road. A little like riding on a magic carpet.

It looked nearly impossible to accomplish, which was a huge lure for Maresca.

“I wouldn’t have come up here if there wasn’t a chance it was impossible,” he says.

He worked for 11 years on the project, which was a technical success but a commercial flop. Their suspension system was too heavy and too expensive for automakers to incorporate into their vehicles without a radical redesign. Plenty were enamored with the performance and said it was the best-riding car they’d ever been in. Jaguar, Mercedes, Honda and Ferrari all were interested. But once they crunched the numbers, they always left Bose at the altar.

MIT legacy

In a coffee-table book entitled “The First 50 Years at Bose,” a single photograph of a tree appears on opposing pages. On one tree, a line dots its way up the trunk in a straight line from point A to B to C to a “finish” point at the top. It represents the status quo thinking about research proceeds. The tree on the opposite page shows points extending to all the branches, and eventually connecting at the “finish” point at the top. This is how Bose said research really works.

Which is part of the reason Bose didn’t specify how MIT should spend the money he gifted the school. Instead, he suggested the money be used to fund orphan projects, those nobody else wanted.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageMaresca and Marty Schmidt, MIT’s Provost and a professor of electrical engineering

Sarah Tew/CNET

Today the dividend pays for four undergraduate scholarships; mundane renovation projects that don’t attract naming opportunities; and unconventional high-risk, high-reward faculty research projects that wouldn’t get funded through traditional grant channels.

“We’re betting on people,” says Marty Schmidt, MIT’s Provost and professor of electrical engineering. Schmidt worked with and knew Bose well. “We’re asking people to come forward with ideas that are really risky, but if successful have a very high rate of return. “

The grants offer up to $500,000 over three years, but MIT doesn’t report exact amounts of each grant, leaving just a touch of Bose mystery in place. Typically four to five projects are funded from a pool of 100 proposals.

Recently, MIT announced the third round of Bose grant winners, which will fund research in magnetism-sensing worms, ancient violins, ionic liquids and malaria microbes. Some of the subjects don’t have an obvious connection to everyday life, but the research into ionic liquids, for instance, might someday help in creating ultrafast rechargeable batteries.

Earl Miller, Picower Institute Professor of Neuroscience and a recipient of a 2014 Bose grant, studies brain waves. More specifically, he studies “how the harmonization of the brain’s rhythms, or brain waves, contributes to consciousness.” He believes, based on his research, that we’re using a lot more than the mythical 10 percent of our brains at any given moment. Unlocking more, like Scarlett Johansson’s character in the film “Lucy,” wouldn’t give us additional abilities.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageEarl Miller, Picower Institute Professor of Neuroscience and a recipient of a 2014 Bose grant.

Sarah Tew/CNET

So what’s the potential high-reward pay-off of his project?

“The brain seems to hum to itself, using rhythms and harmony for communication,” Dr. Miller explains. “This humming helps different brain networks talk to one another. We hope to use TES [transcranial electrical stimulation] to boost the humming in a way that will improve brain communication.”

He conjectures that may also offer new treatments for diseases such as ADHD, schizophrenia and autism. Maresca is interested in all this on a personal level because he has a younger brother with severe autism.

Envisioning the possible

Leaving the professor’s office energized, it’s apparent that Maresca gets a rush from being around people who are pushing the research envelope, trying to obliterate preconceived notions of what’s possible.

Steve Jobs once said, “A lot of times people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” The way he said it came across as arrogant, more like we know what the customer wants and we’ll give it to them.

Maresca says Bose agreed with Jobs. He eschewed focus groups — no one dared say the words around him. But Bose believed the reason people didn’t know what they wanted was they didn’t know what was possible.

Enlarge Image

Enlarge ImageDownplaying his personal accomplishments, Maresca points to the talented team that made up the Noise Reduction Technology Group, which he previously led.

Sarah Tew/CNET

“One of the benefits of studying technology and being on the cutting edge is that you can envision what it might be,” Maresca says. “Now it’s important to ask people what their problems are, not what products they want.” Define the problems and use technology and innovation to solve them.

So what is the cutting edge for Bose? Everybody talks about making products for those millennials, but what about all those baby boomers losing their hearing? Bose must have products in the pipeline for them. How about a wireless headphone for watching TV in the den?

Maresca smiled at my question.

“You want to open your presents before Christmas?” He paused a moment, then added, “I’m not at liberty to discuss research, but I’m very interested in that.”