An avid player of Electronic Arts’ “The Simpsons: Tapped Out” mobile game, David Lamb was disheartened when he logged into his account in October and found that all of the data from his game was gone.

The iOS game, which is essentially “Farmville” with Springfield buildings and Simpsons characters, rewards players who spend huge amounts of time completing tasks and collecting money in an effort to re-create their favorite animated city. Lamb, a 45-year-old video editor from La Canada, Calif., had accumulated $80,000 in game cash and 70 donuts (the game’s premium currency) after playing for a month.

Then, it vanished. There weren’t even digital tumbleweeds.

“I was very proud of my town and how I had built everything,” he said. “It was a creative outlet for me. So to suddenly have everything go away is very upsetting and frustrating.”

More than two months later, Lamb still hasn’t gotten his city back. Aside from a generic response that EA is looking into the problem, he has gotten little feedback or reason to be optimistic. Judging by the complaints the game has racked up in its forum, Lamb isn’t alone.

Updated at 1:29 p.m. PT on Saturday: David Lamb has told CNET that after the story came out, EA contacted him and restored his lost Springfield and gave him 200 donuts for his trouble.

The “Simpsons” glitch underscores the difficult transition that traditional video game publishers have to make as they move from the traditional model of selling a title and moving on to offering a game that requires continued support and attention. The new era of “freemium games” like “The Simpsons,” where players can play for free, but can pay for premium upgrades, further complicates matters. Lamb, for instance, didn’t sink any cash into the game, but still invested a lot of hours that he now feels have been wasted.

Navigating this transition is Michael Lawder, head of customer service for EA. Lawder has spent the last two years overhauling the mindset of the organization, shifting the mentality away from a single product, and toward services. He told CNET that he expects big changes to occur next year as it enters year three of his three-year plan to change how EA treats its customers.

“I think we will see a dramatic shift in the company,” Lawder said. “We’re not there yet. There’s still a ways to go before we’re considered a world-class customer experience.”

It’s not hard to imagine anyone with a good knowledge of the industry chuckling at that last line. If anything, EA’s reputation is the opposite of world class. The company has long been a favorite target for the wrath of gamers, who complain about poor service and perceive the company as a greedy monolithic entity swallowing up and destroying smaller, more innovative game makers.

In April, the blog Consumerist voted EA as the “the worst company in America,” noting it handily beat Bank of America, which doesn’t exactly have a lot of fans after the housing crisis and financial bailouts. A Google search for the terms “Electronic Arts customer service” comes back with 19.2 million results; a similar search for “Electronic Arts customer complaints” yields 79.1 million results.

Whether EA is really the worst company in the country is debatable; after all, it makes video games, and hasn’t caused anyone to lose their homes or jobs or ravaged the wildlife of the Gulf Coast. But the fact that it took the top spot highlights the strong feelings the company elicits from its customers.

That’s the kind of challenge Lawder faces as he attempts to turn around the company’s customer service efforts. Lawder spent 11 years at Apple working on its customer service and believes he can bring the same kind of changes to EA. He also believes that in an industry that has gotten its knocks for poor service, EA could eventually stand out if it can deliver, which could translate into better customer retention.

Over the last two years, Lawder has opened two customer service centers, one in Austin, Texas, and the other in Galway, Ireland, along with 10 contact centers around the world. The company recently said it would hire another 200 employees for its Galway facility as part of a partnership with the Irish government.

“Rather than outsourcing customer service, we’re focused more on high-quality personal experiences,” he said.

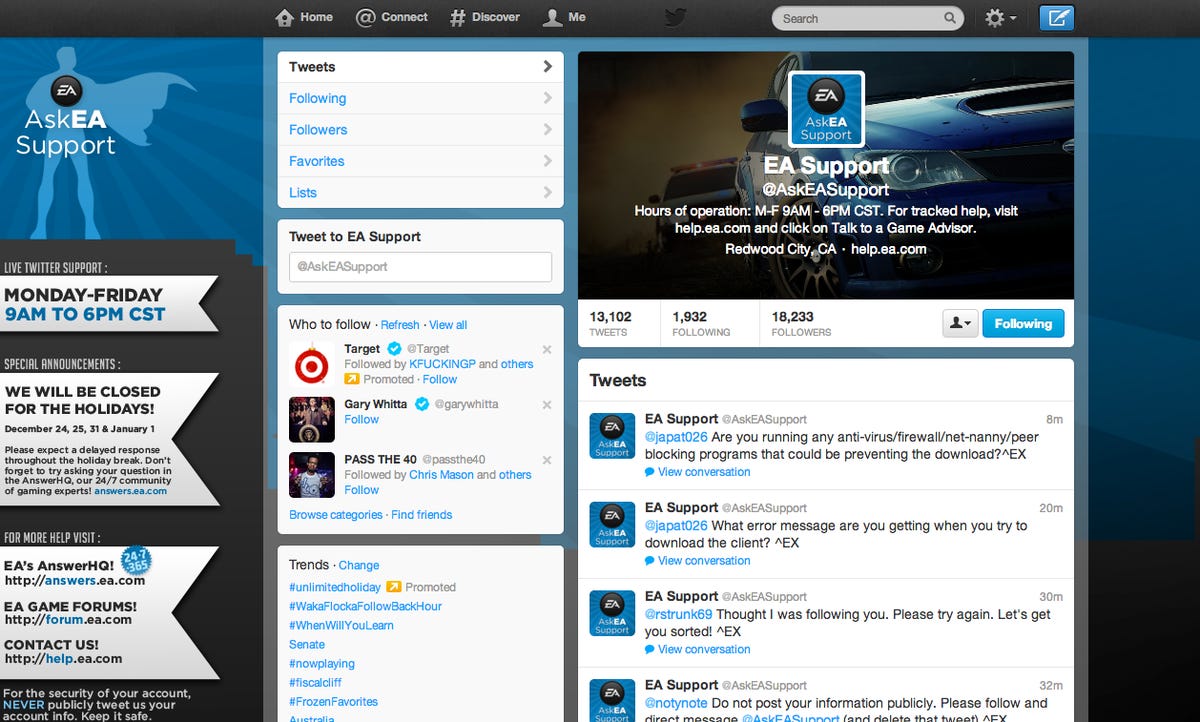

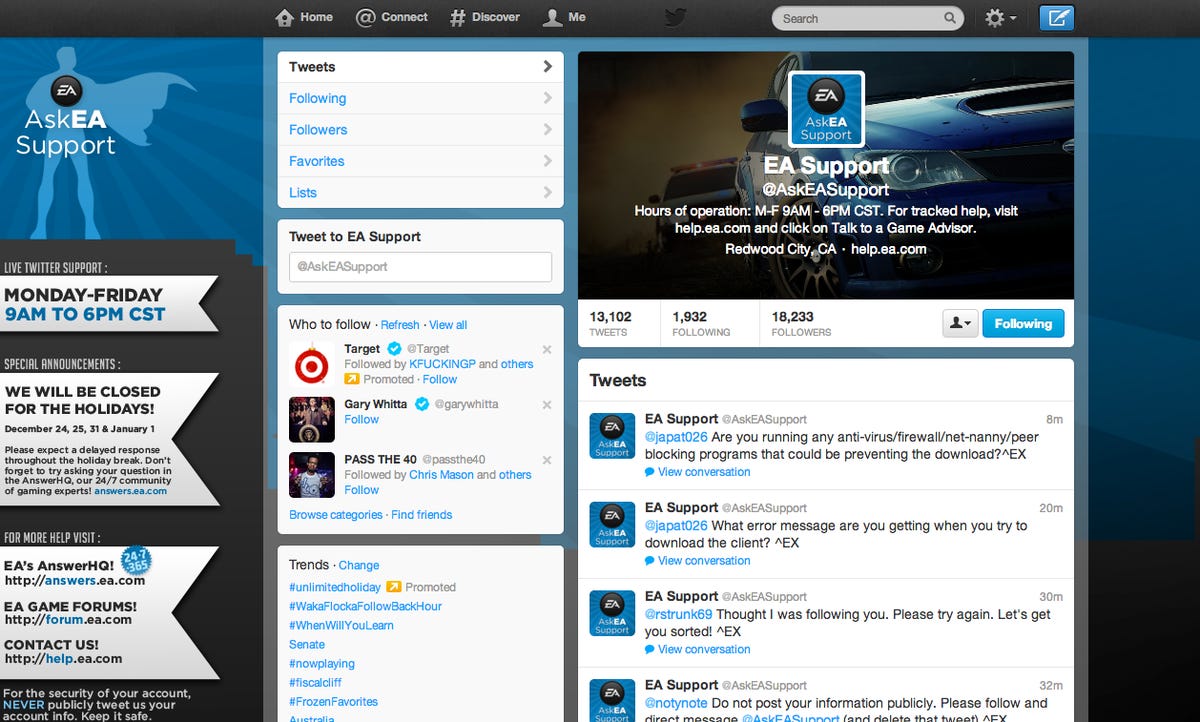

The company launched a new Web site, help.ea.com, and an online support community called AnswersHQ. It has also bulked up its social presence on Facebook and Twitter. It has also invested in proprietary cloud-based tools that provide customer service representatives with information on gamers, including the titles they own, the kind of achievements or entitlements they have, so they are more informed when helping them.

EA

EA is also looking at different ways of solving problems, including rewarding experienced players with experience points, perks, or other rewards for helping their peers, or having assistance and technical support embedded in games. The support includes hints and tips, as opposed to just fixing something when it’s broken.

These new models are being put in place as video game companies juggle the trend of freemium games and additional downloadable content with investment in continued customer support. While “The Simpsons” game remains a top-grossing game in the Apple App Store, a vast majority of its players never pay a cent to play. Lawder said the company is beginning to recognize that those players may not bring a financial benefit, but they do add a lot of social value. Yet EA still has to justify some investment to support “The Simpsons” and other freemium games.

“If you have no return on investment, you can’t spend millions of dollars supporting them,” he said. “That’s where social community support comes in.”

The systems being put in place will help EA remedy some of its problems quicker, Lawder said. They would also help the company develop a closer relationship with the customer. Instead of a generic e-mail about the latest “Madden NFL” game for the Xbox 360, gamers would get messages tailored to their preferences and gaming history across different platforms.

So, the work done over the last two years begs the obvious question: why are things still bad?

In reality, EA has made some strides, according to Lawder, noting that customer satisfaction has risen.

“We’re nowhere near where we need to be,” he said. “We can do a lot better, but there’s been some progress.”

He noted that while at Apple, it took five to six years for the company to build the sterling reputation that it enjoys now. When he started at Apple in 1999, the company was still selling to other retailers, and had just gotten started with its retail and online presence. He helped build up the customer service part of the business and was “deeply involved” with the first iPhone launch, he said.

Perception does lag reality at times. A company with a wounded reputation could offer the best service, but still be stuck with a bad reputation for years. Sprint Nextel, which burned many of its customers early after the Sprint and Nextel operations merged, spent years rehabilitating its brand, and has only recently been seen as competitive with larger rivals Verizon Wireless and AT&T.

“The problem is that expectations are so high, it becomes tougher and tougher to overcome disengaged customers,” said Robert Passikoff, president of marketing consultancy Brand Keys.

So what’s Lawder’s take on working for the “worst company in America”?

“I didn’t put a lot of stock into it,” he said, admitting that it was annoying. “What I can tell you, there’s not a person I’ve met at the company who isn’t passionate about the customer. I’ve been really impressed. It’s something I didn’t expect coming here.”

As for “The Simpsons” glitch, Lawder said the company is still learning from the different kinds of games EA is moving into, such as the game’s server-driven architecture. He said the company is working with the specific label to address the specific problems faster and keep players in the loop.

“It goes back to transparency,” he said.

EA said the glitch affected less than 1 percent of “The Simpsons” players, but that it is attempting to work directly with the affected players to address their problems. The company pointed to this address to get help.

As Lawder alluded to, EA still has a lot of work ahead of it. Lamb has attempted to use EA’s various resources, but is still without his Springfield.

“The information there is too generic to be of any help,” he said of EA’s help Web sites.

For Lamb, EA’s new changes can’t come soon enough.

Screenshot by Rick Broida/CNET