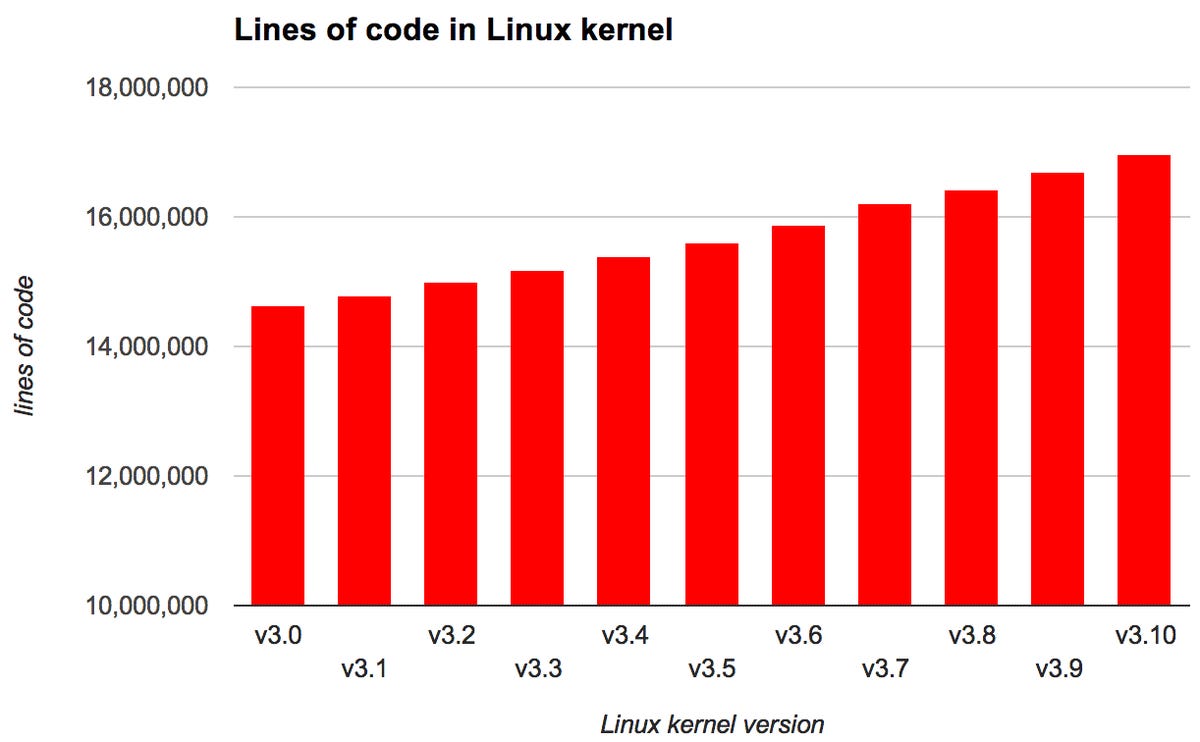

Linux is growing — that we knew. Now we know how fast.

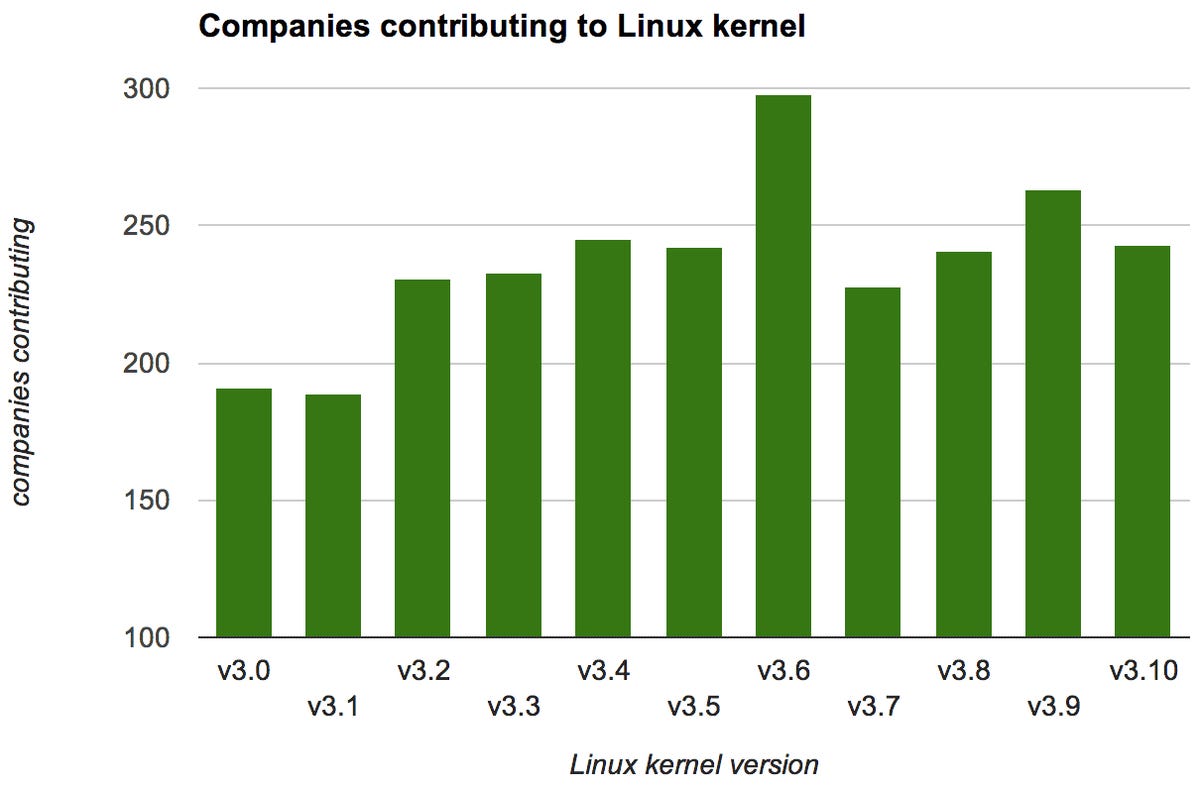

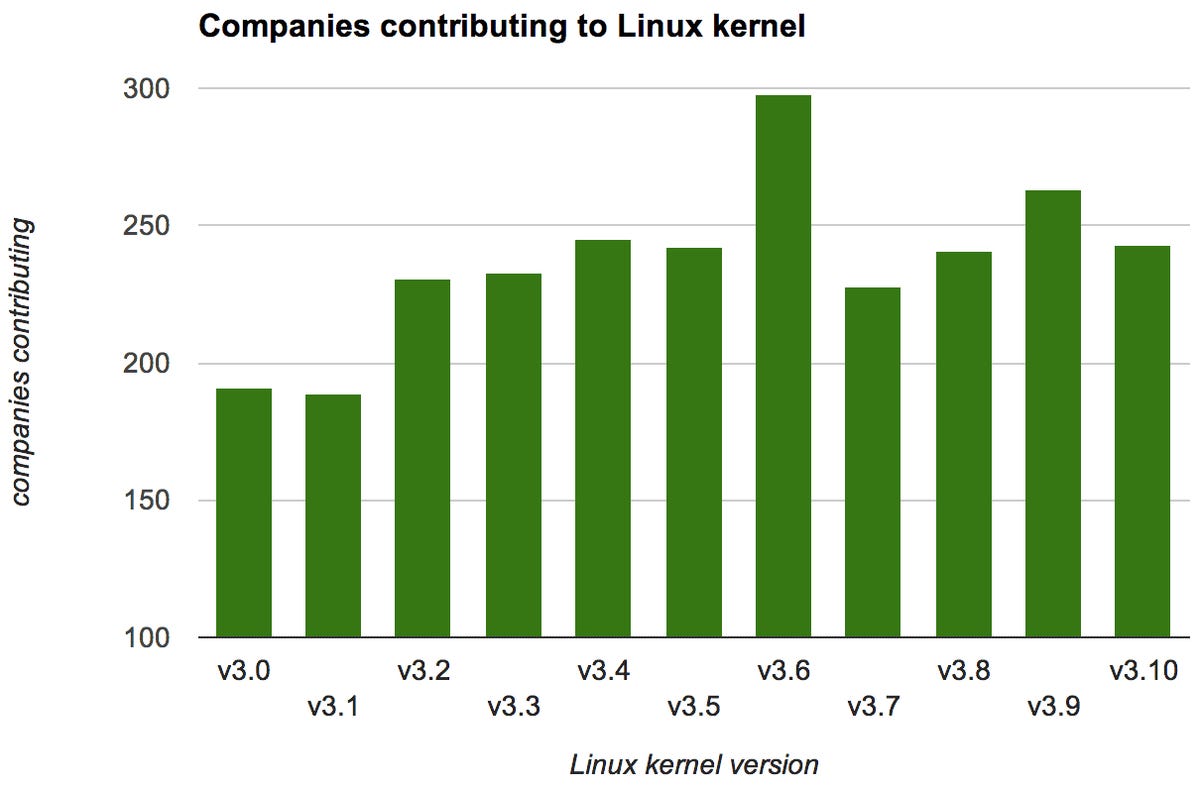

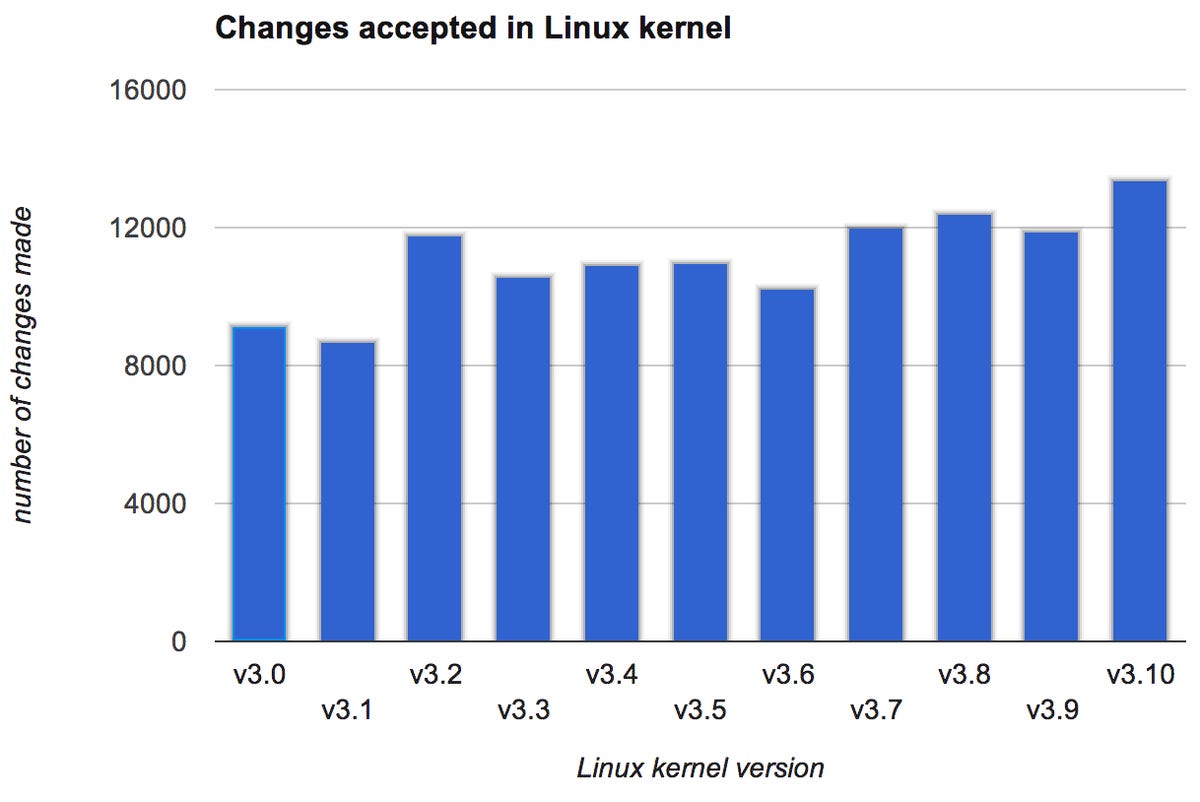

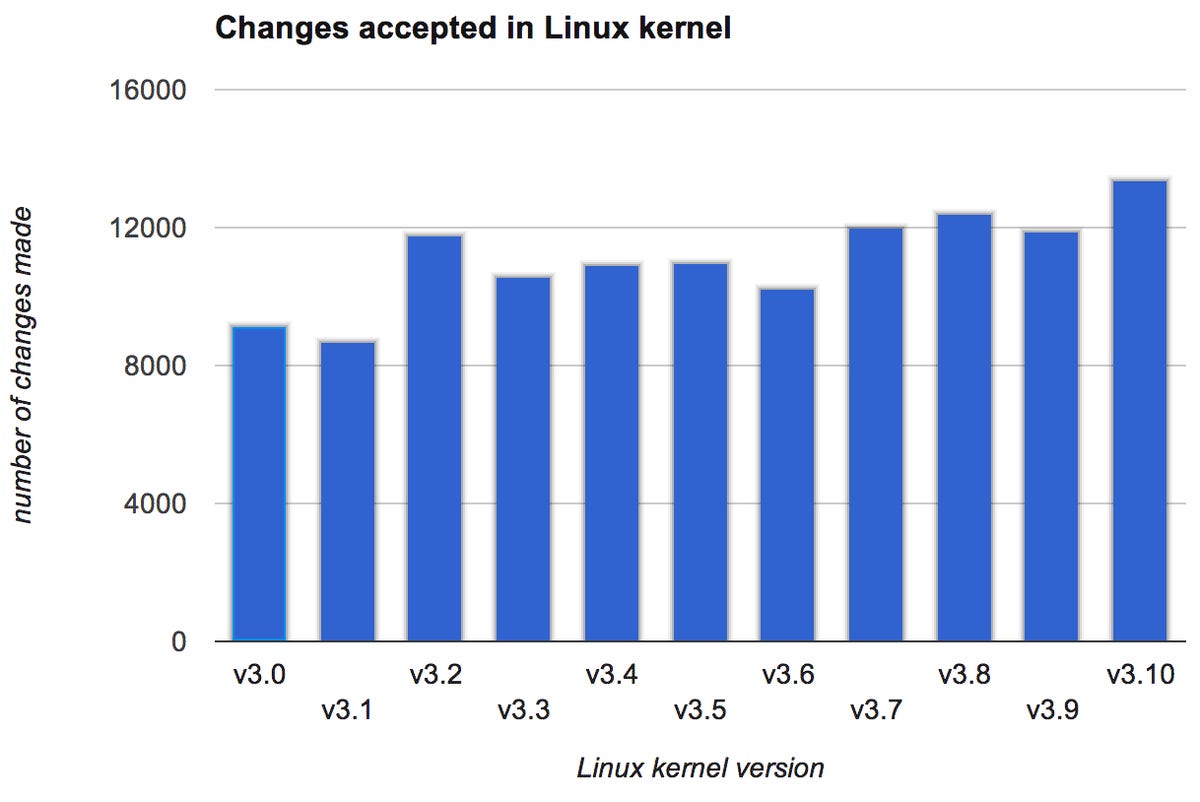

In the last two years, the number of developers who collectively create Linux has increased from 1,131 with version 3.0 in July 2011 to 1,392 with version 3.10, released in June 2013, according to the Linux Foundation’s latest annual Linux development report. Also on the rise: the lines of code in the project, the number of changes accepted into each new version, and the frequency at which those changes arrive.

“This rate of change continues to increase, as does the number of developers and companies involved in the process; thus far, the development process has proved that it is able to scale up to higher speeds without trouble,” the study concluded.

data from Linux Foundation; chart by Stephen Shankland/CNET

Linux — technically just the kernel at the heart of the open-source operating system that often goes by the same name — has never attained the kind of widespread consumer recognition of OSes like Windows and iOS. Nevertheless, its clout continues to increase: it powers everything from Facebook’s mammoth data centers to Google’s Android.

That utility is reflected in statistics published roughly annually by the Linux Foundation, the organization that employs Linux creator and overseer Linus Torvalds among others; the foundation published its September 2013 report Friday. The foundation tracks statistics using the Git source-code management tool that Torvalds wrote when unsatisfied with the earlier options. It’s no Linux, but Git now has spread far and wide, too, as more and more discovered its utility at managing programming projects distributed among many developers.

Linux itself is probably the best example of such a widespread project. The recent version 3.10 of the kernel, released June 30, 2013, drew updates from 1,392 developers at 243 companies. That’s up from 1,131 developers at 191 companies for version 3.0, released July 21, 2011.

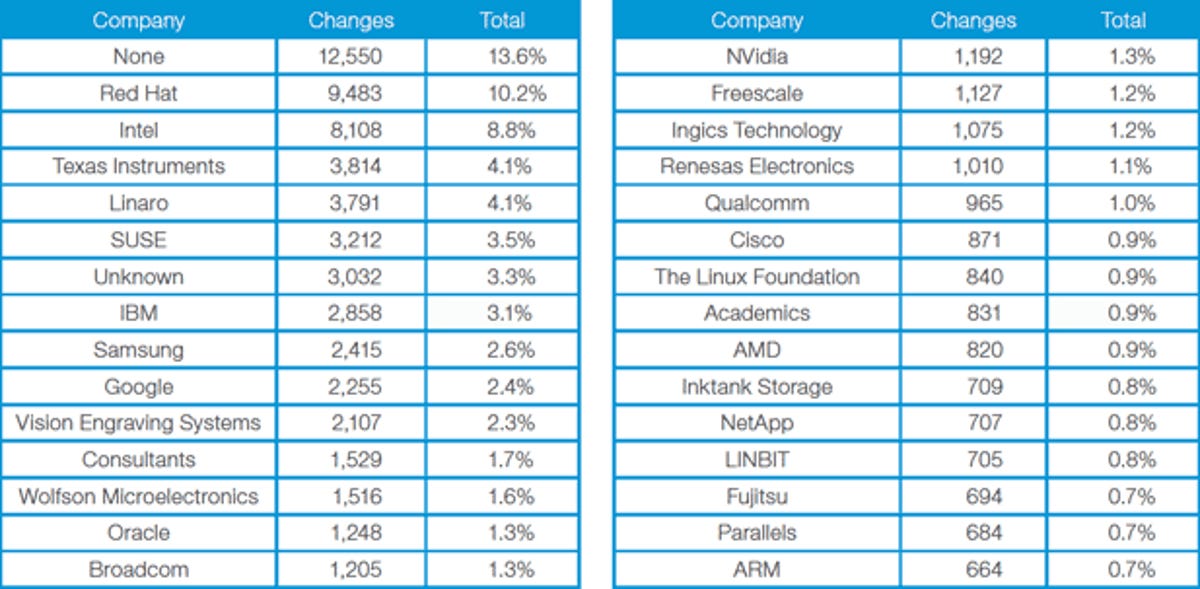

Linux Foundation

“Since the beginning of the git era (the 2.6.11 release in 2005), a total of 9,784 developers have contributed to the Linux kernel,” the report said.

That breadth isn’t evenly distributed, of course: a small number of programmers produce much of the code patches that are applied to the kernel and vice-versa.

“In any given development cycle, approximately one third of the developers involved contribute exactly one patch,” the report said. “Since the 2.6.11 release, the top ten developers have contributed 30,420 changes — 8.4 percent of the total. The top 30 developers contributed just over 18 percent of the total.”

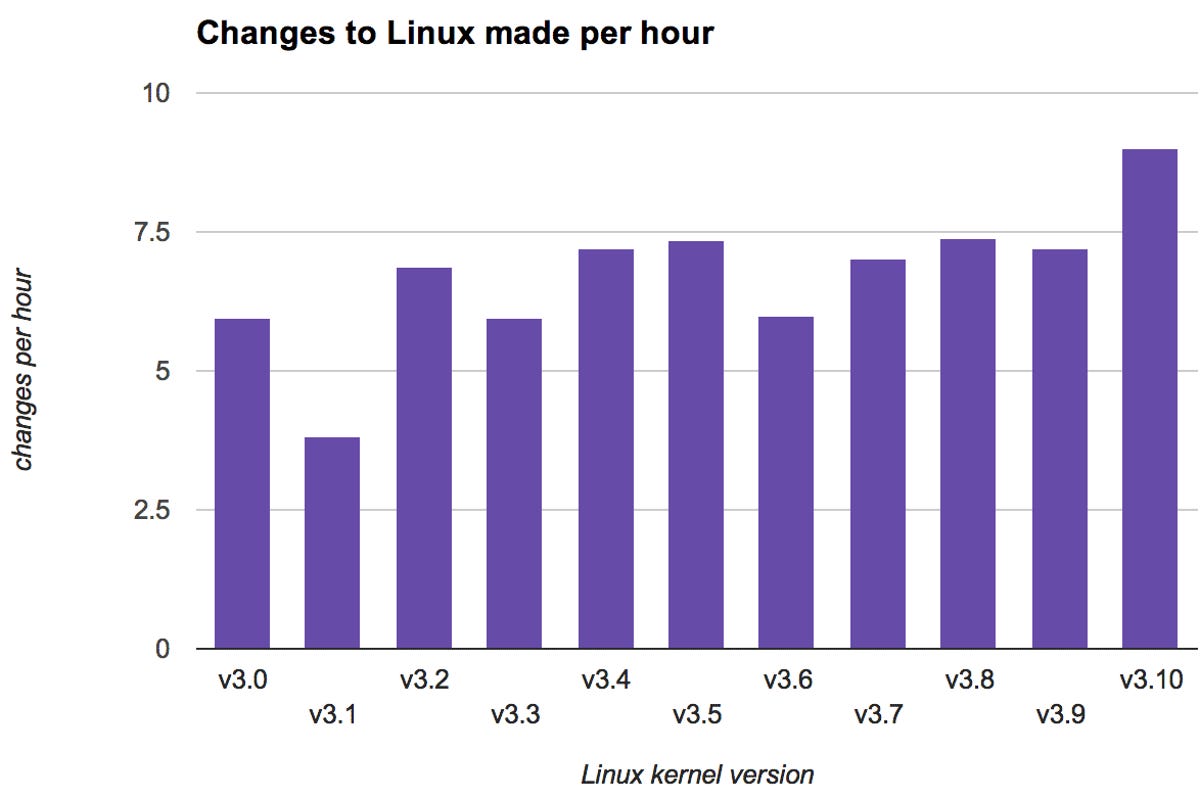

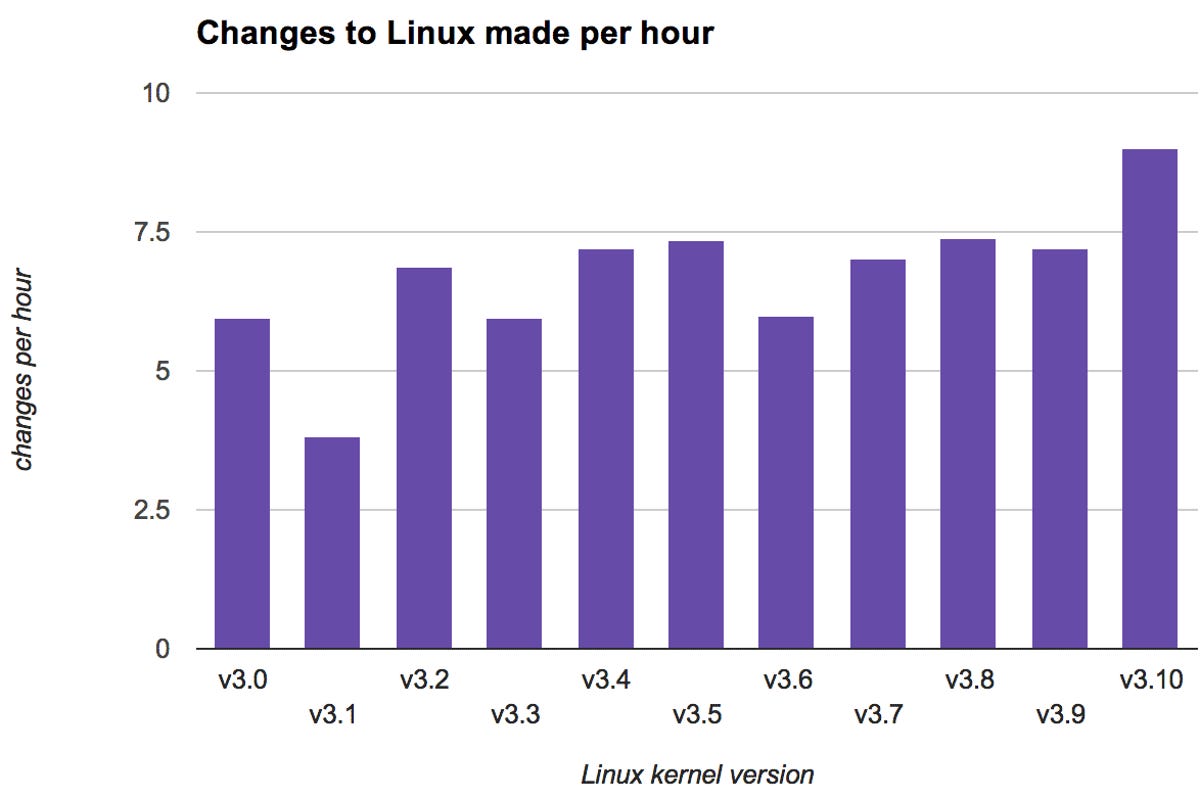

data from Linux Foundation; chart by Stephen Shankland/CNET

Some people think of open-source software as a hobbyist phenomenon, and there’s plenty of that, to be sure. But the vast majority of Linux work is done by paid professionals these days.

In terms of patches accepted into Linux, the top 10 contributors are Red Hat, Intel, Texas Instruments, Linaro, SUSE, IBM, Samsung, Google, Vision Engraving Systems, and Wolfson Microelectronics. Among other developments, mobile technology companies including Texas Instruments, Samsung, Google, and Qualcomm have a serious presence, support for 64-bit ARM processors arrived over the last year, and spat between Google’s Android team and other kernel programmers was resolved.

data from Linux Foundation; chart by Stephen Shankland/CNET

One big contributor in 2012 was Microsoft, which submitted 688 patches so that Windows could get along with Linux in virtualization environments — a technology where a single computer runs multiple operating systems atop a lower-level OS. It’s a widely used approach in the server market to achieve greater hardware efficiency. Apparently Microsoft considers the work done, though, because it dropped off the list of contributors for the 2013 report.

Although new kernels arrive about every two months, a few of them get long-term two-year support with fixes for bugs and security problems. Those versions — 3.0, 3.4, and 3.10 in the last two years — are typically the foundation of commercial products.

data from Linux Foundation; chart by Stephen Shankland/CNET