James Martin/CNET

All of a sudden, Eric Valor struggled to surf.

His left foot started dragging while he tried to pop up on his board, causing more wipeouts than normal for the avid wave rider. What started as a visit to the foot doctor resulted in an eventual diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, an incurable neurodegenerative condition with few known causes that bit by bit takes away a person’s ability to control muscle movements and leads to death.

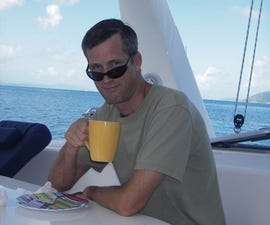

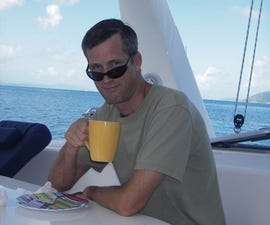

Courtesy of Eric Valor

“The gravity of that day,” he said of when he was diagnosed, “of the terrifying fear, volcanic anger, the inconsolable sorrow for the loss of the perfect life my wife and I had built — still remains as a stark and adrenaline-inducing memory.”

Valor — a 45-year-old former information technology professional living outside Santa Cruz, Calif., who is now paralyzed — built a new life as an advocate for the ALS community. That calling led him to take part in an experimental project this year developed by consultancy Accenture and tech firms Royal Philips and Emotiv. Using Valor as their first trial case, the companies successfully used Emotiv’s wireless brain-wave-reading headset to allow him to request medical help and control the lights or television simply by thinking commands.

This kind of technology could in the future help people paralyzed by diseases or injury to communicate with others, control different facets of their homes without someone else’s help and gain mobility by operating a wheelchair.

“We’re just excited about the potential of what this product can provide,” said Tan Le, CEO of Emotiv. “We’re just scratching the surface.”

Now playing:

Watch this:

Brainwave tech could help ALS patients control appliances

2:32

ALS is relatively rare, with roughly 400,000 people worldwide affected, which means the battle for a cure or treatment is sometimes overlooked in favor of more well-known afflictions. But over the last month, awareness of the disease has gone mainstream thanks to a viral campaign called the Ice Bucket Challenge — you might already have been called out by someone on your social network to dump ice water over your head.

Courtesy of Eric Valor

The Emotiv project, which isn’t connected to ALS charities, is one of several efforts in researching brain-computer interfaces, which capture electric signals in the brain and translate them into specific commands. These technologies could be used to solve the complex problem of giving paralyzed patients a means of communication and independence even when they can’t type or speak or provide any other physical inputs into a computer.

The technology would be especially useful in later stages of ALS, when some patients lose all ability to move, unable even to blink or move their eyes. Such patients are locked into their bodies despite maintaining alert minds. The effort also offers a window into the potential of wearable consumer technology and so-called smart-home devices for a higher calling than their current uses such as fitness tracking and email alerts.

Still, the teams at Emotiv, Philips and Accenture cautioned that their work remains in the early days of development. “It’s far, far too early to even know whether this has a potential to be a product,” said Anthony Jones, a marketing executive in Philips health-care business. “We’re at step one of a very lengthy, multistep process, but a significant step.”

Valor and ALS

In 2005, Valor was 36 years old and working as an IT professional for car maker Daimler’s North America research and development operations. He had a house by the beach, near his current home in Aptos, Calif., where he could surf regularly, and he was happily married. At the time, he said, he was ready for the next step of his life, looking forward to becoming a dad. “All that was taken away,” Valor said.

His first symptoms were visible muscle twitches. Then, he found he had trouble surfing, a regular hobby along with snowboarding and scuba diving. An evaluation by a foot doctor led to a trip to an orthopedic surgeon, followed by a referral to a neurologist, then to UCSF Medical Center hospital. Valor hoped for cancer or another illness that might be cured. His ALS diagnosis came soon after. By 2008, he couldn’t control a computer mouse and he retired as a network operations manager overseeing several US offices for Daimler.

James Martin/CNET

Valor transitioned to using an infrared camera that can track his eye movements across his computer monitor to allow him to write. He wears a sensor taped to his cheek that, when he twitches, can activate a buzzer to call an attendant. His meals are served to him via a feeding tube. He is hoisted onto a rolling transport chair for showers. A machine helps him breathe. Despite his condition, he discusses how he refuses to “go away,” now writing a blog chronicling his life with ALS, participating in drug trials, and advocating for the ALS community.

Writing to CNET using eye-tracking technology on his computer, he said he keeps busy socializing online, helping other ALS patients with their computers, and managing different projects involving the ALS community. “I am fulfilled in this new career,” he said.

James Martin/CNET

Using Insight

Valor’s ALS outreach led him to the Emotiv project, and his background in IT made him an obvious fit for the test.

Emotiv, founded in 2011, is among a handful of companies, including InteraXon and NeuroSky, working to take electroencephalography, or EEG, technology — which has been used by doctors and scientists for decades to study brain activity — and bring it into the consumer world. These commercial devices, which use EEG sensors to decipher the brain’s electrical activity along the scalp, offer users a way to track brain health and provide a new form of gaming.

Emotiv currently sells a wearable headset called the EPOC, which starts at $399, that’s used for research, and it plans on coming out with a second headset called Insight for consumers in early 2015, starting at $299. Both devices are simply worn on a user’s head and don’t require any implants or surgery, so they can be removed about as easily as a hat.

James Martin/CNET

The battery-powered Insight, which Valor used in the experiments, is intended to be a wearable device for everyday use by anyone to assess brain health and well-being. The device can interpret brain signals, allowing a user to perform a handful of commands on devices compatible with the headset, including flying a toy helicopter, using only their mind.

Valor could use the Insight headset to send commands by thinking certain words, such as “down” or “right.” Those commands were then transmitted over to a tablet computer and processed through Accenture and Philips software to control a handful of Philips products, including the Lifeline medical alert system, a television, and lighting. The commands also appear on an eyeglasses display device, providing feedback to Valor.

Valor said there were obvious advantages to the Emotiv headset. He noted that the headset seems to work in sunlight, when the infrared eye-tracker could be more challenging. In more serious cases, two of his friends lost the ability to move their eyes, and thus their last mode of communication.

Brain-wave headsets

Valor and others affected by ALS have a spectrum of technologies available so they can function as much as possible like they did before the disease hit. Once a patient loses more motor abilities, they can transition to another type of technology, such as switching from tapping on a tablet to visual inputs with an eye-tracking sensor. However, once full paralysis takes place, there often is no way to reach out anymore. Jacquellyne Hengst, director of development at the Philadelphia-based ALS Hope Foundation, said that for those patients served by her organization, she will sometimes simply sit with them, hold their hand and look into their eyes.

Now playing:

Watch this:

ALS patient more independent with tech

3:12

For those cases, brain-computer interfaces, or BCIs, hold promise, though the technology remains mostly in the research phase. Such technologies could allow people with extreme physical disability — including those with ALS, brain-stem strokes or cerebral palsy — to type out an email, operate a robotic arm or wheelchair, or move a cursor by using their thoughts.

Sara Feldman, a physical therapist and assisted-technology professional at the MDA/ALS Center of Hope clinic, which is funded by the Philadelphia foundation, said many patients most fear losing the ability to interact with others. Any technology, she said, that could provide a channel of communication for patients who can’t move would be life-changing.

Mind control making life with ALS better (pictures)

+8 more

“It is so important, because communication is so important to people,” said Feldman, who wasn’t involved in the Emotiv project. While her organization takes part in projects involving brain-computer interfaces, she noted, “That’s taking a lot of time and research.”

So far, the next step for Philips, Accenture and Emotiv is unclear. The team said they were able to prove their idea works and wanted to talk about it publicly to draw in more ideas and attention to see if that concept can one day reach the market. But there remain more questions, including how to ensure the system can function for patients at differing stages of ALS. Also, converting Emotiv’s Insight headset into a medical product would require substantially more reliability and stress testing, Emotiv CEO Le said.

James Martin/CNET

“There’s definitely a lot of excitement about what we’ve built,” she said. “It makes all the work really humbling and very worthwhile for our team.”

Valor called the system the team developed “revolutionary and technologically ahead of its time.”

He added that there was great potential for a brain-wave-reading headset like the Insight, saying the technology could offer a path for scientist Stephen Hawking, who has lived with ALS for decades, to continue producing works.

“The potential for this technology to reawaken and restore multiple beautiful minds to this world is staggering,” he said. “We are writing the pages of science fiction becoming fact. It is amazing to be a small part of it.”