I strapped a familiar-looking Oculus Rift headset over my eyes. This one’s been doctored: Around the lenses, a ring of sensors has been implanted. In front of me, what appears to be a foot away, there’s a screen. I see my own eyes, looking back at me. And they’re dilating.

Eyefluence is a startup that claims it’s cracked the code to eye-tracking in head-mounted displays, and the result could change how you interact with virtual reality and augmented reality headsets in the future. The technology is a mix of advanced eye-scanning and eye-tracking hardware, plus a special sauce of user interface language that, according to co-founders Jim Marggraff and David Stiehr, can let you do things with simple eye motions without fatigue. Instead of using a trackpad or turning your head to aim at things in virtual reality, the goal here is to let subtle eye-flicks navigate around virtual interfaces. No hands required.

I interviewed Marggraff and Stiehr in a small meeting room in downtown Manhattan. As I sat in front of a desk covered with exposed hardware, connected laptops and specially-rigged smartglasses, it felt a little bit like a Terry Gilliam film.

Marggraff, an electronics industry veteran and inventor who founded Livescribe and invented Leapfrog’s LeapPad learning system, puts a pair of retrofitted ODG R6 smartglasses over his face. Exposed wires and circuits run down to an extra piece of hardware with spokes attached. It’s tethered to a laptop, so I can watch what he’s doing. He’s controlling augmented reality with his eyes, he explains. And with two minutes’ training, so can I.

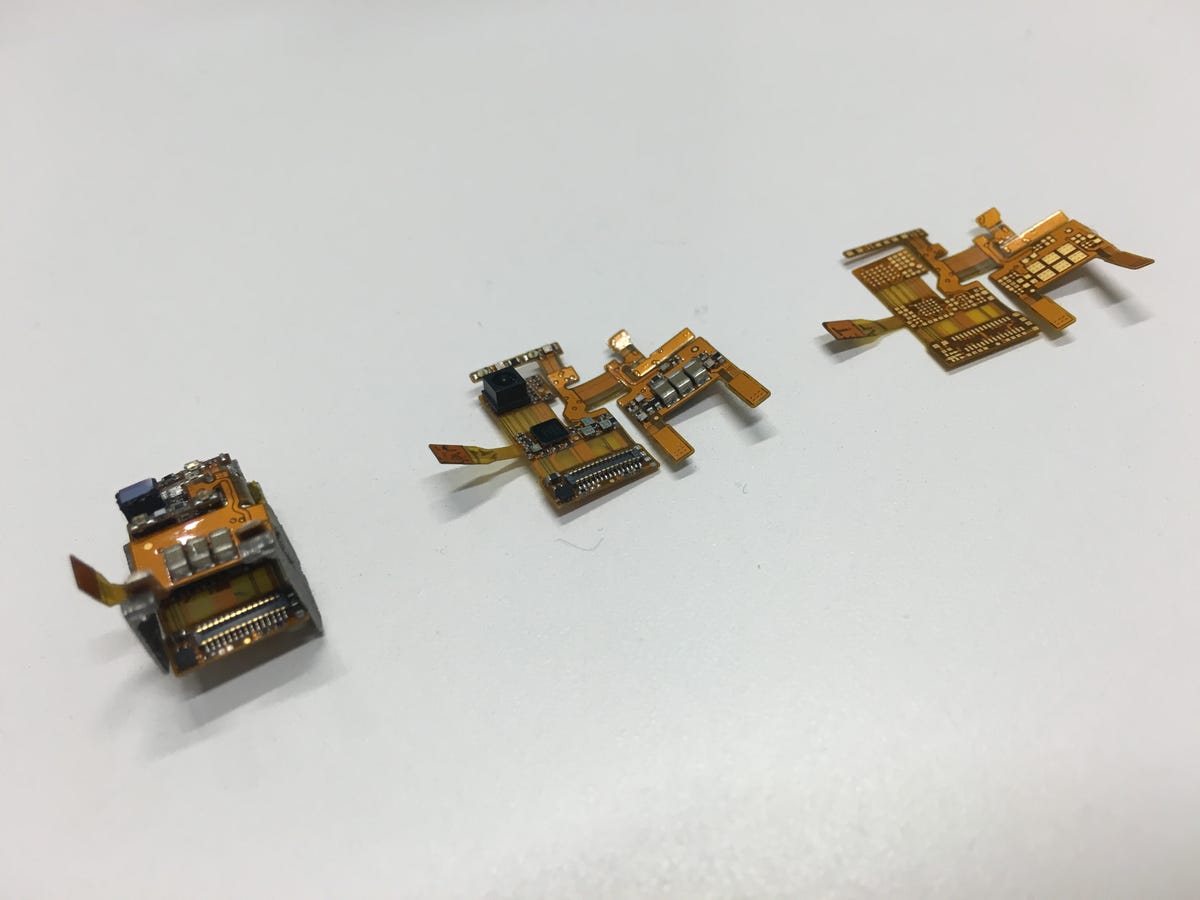

Eyefluence’s eye-tracking hardware prototype is bonded onto a pair of smartglasses.

Scott Stein/CNET

He looks around a menu of icons — folders, or concepts for what apps would look like on a pair of next-gen smartglasses. He opens one up. He browses photos, zooming in on them. He looks at a box of chocolate on the desk, scanning it and showing how he could place an order using eye movements. He types out numbers on an on-screen keyboard. He sends quick canned texts to Stiehr, which pop up on the latter’s phone.

According to Marggraff, eye-tracking itself isn’t unique. But the ability to use the natural language of eye movement just hasn’t been invented yet. Much like swiping and pinching on touchscreens helped invent a language for smartphones and tablets after Apple’s iPhone, Marggraff said the smartglasses and VR landscape is in need of something similar for eyes. Even though we can use controllers to make things happen in VR, it’s not enough. I agree. Turning my head and staring at objects always feels a lot more weirdly deliberate than the way we look at things in the real world: by flicking our eyes over something and shifting focus.

Now playing:

Watch this:

Eyefluence dreams of your eyes controlling VR without…

0:58

Doing magic things with my eyes

I don’t get to demo the smartglasses, but I do train with the Oculus headset. First I look around, getting used to a simple interface that involves looking at things, but no blinking required. (In exchange for this early look at the technology, they asked me not to disclose the full details of how Eyefluence’s interface works. That’s partly why there are no pictures of that here.) Stiehr and Marggraff seem briefly concerned about my eyeglass prescription, though. Mine’s an extreme -9. Eyefluence corrects for light, glasses and other occlusions, but mine might be a bit too extreme for the early prototype demo.

Everything does indeed end up working, though a few glances at the corners of my vision seem jittery. I get better the more I use it. Soon enough, I’m scrolling around icons and even opening them. I open a 3D globe. I spin around it using my eyes, resting on different places with quick glances. It almost feels, at times, like telepathy.

Another demo had me try VR whack-a-mole. With something like a regular VR headset, you’d move your head and aim a cursor at things. I try the little arcade game this way, then it’s triggered over to eye-motion mode. Suddenly I’m zipping across and bonking the pop-up arcade critters with sweeps of my eyes. An after-the-game set of stats shows I was about 25 percent faster using eye-tracking.

Finally, I open a little game of Where’s Waldo? A large poster-size illustration opens up, full of people and things. I’m encouraged to look at something in the picture, then move my eye to a zoom-in icon. The picture zooms on what I was looking at. It feels like a mind-reading magic trick. It doesn’t always work on my first go, but when it does it’s uncanny.

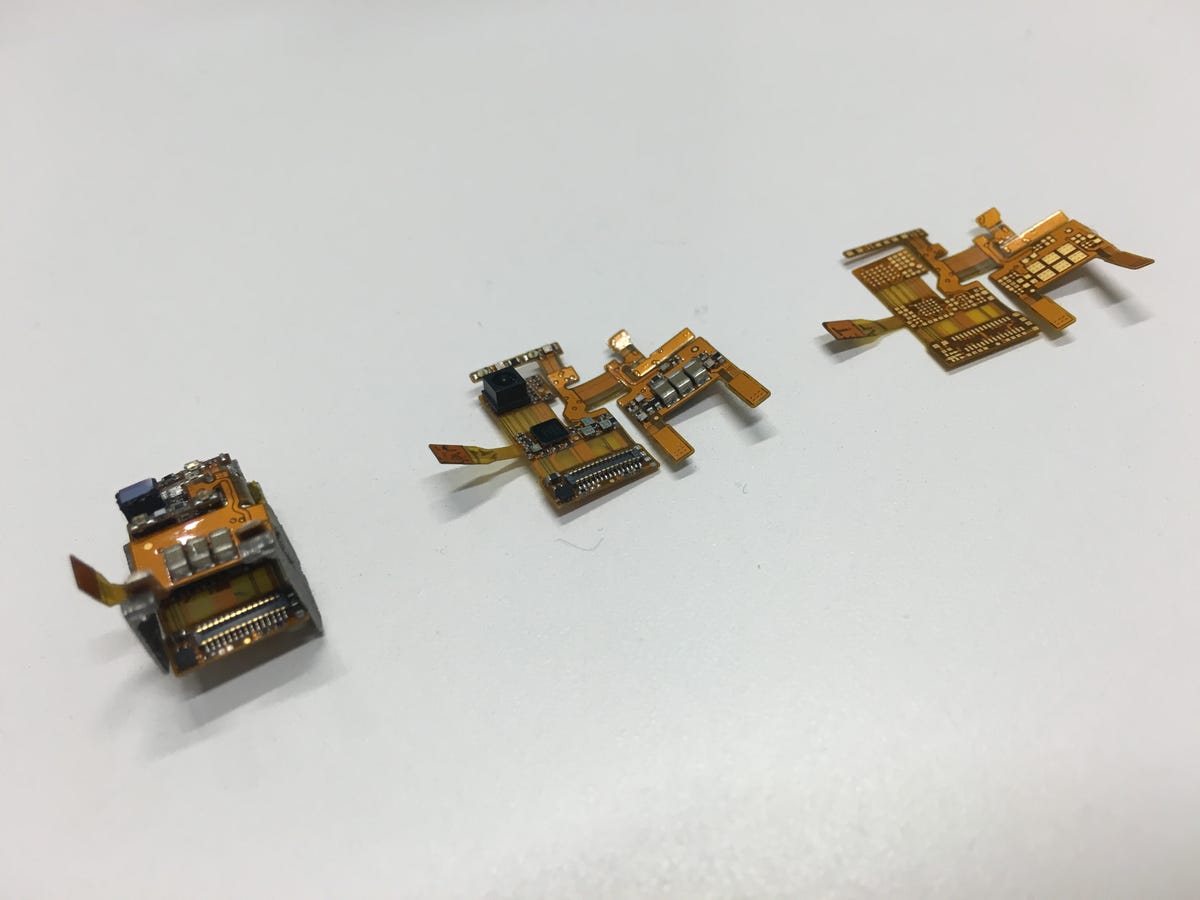

Eyefluence’s evolving hardware is small, flexible and designed to fit into other devices.

Scott Stein/CNET

Eye power

Eyefluence’s tech doesn’t just track eye motion. It also scans retinas. The combination can be used for biometric security (think enterprise smartglasses that could log you into corporate systems automatically), or for future medical applications. Stiehr, who helped create some of the first automatic defibrillators seen at airports and other public places, has a background in launching medical technology companies. Many of Eyefluence’s employees have backgrounds in neurology, Stiehr said, and he sees the company’s advances as being part of a solution for diagnosing epilepsy, concussions and Alzheimer’s and for possibly helping to retrain patients with autism. The concept of controlling an interface completely with your eyes would be amazing for people who are disabled or paralyzed.

Since Eyefluence’s eye-tracking also keeps track of where you’re looking — and how much your pupils are dilated, which can indicate emotion or engagement — heat maps for advertising, fashion or really anything could be assembled. Imagine glasses that know what you’re looking at, and maybe that can even guess what you’re feeling.

One ready-to-go feature for eye-tracking that’s a lot more practical is called “foveated rendering.” It’s an ability for VR graphics to focus their higher-resolution rendering to just a small area where you’re actually directly looking, and dialing down the resolution around the periphery to save processing power. Our eyes already perform a little bit like this. Our peripheral vision isn’t as crisp as what we see in the center of our retinas. I try a demonstration, looking around a virtual castle that’s rendered around me. The focus circle of where I’m staring becomes extra crisp, while everything around that goes blurry…like looking through fog. Sliders are adjusted until the effect evens out, and then I can’t even tell the rendering trick is happening. I’m assured that it is. The bottom line is that tricks like this could potentially let people run advanced VR graphics on far less powerful PCs down the road.

Looking in

There are plenty of companies exploring eye tracking in virtual reality headsets, smartglasses and other head-mounted displays. Oculus has been exploring it, along with others like Fove. I’ve never used eye-tracking in VR before. But I’m sold on it now.

I agree with Marggraff. The eye tracking needs to be easy to use and understand. My brief demo was fine. Would it tire me out over a half hour of use? I’m not sure. And a lot of the demos that I experienced involved navigating across 2D screens, not true 3D virtual spaces. Will eye-tracking alone work in more complex 3D realms? (Probably not. You’d more likely combine eye tracking with hand controls.)

But I’m starting to realize I can’t imagine virtual reality, and especially next-generation smartglasses, without this type of technology. Looking out via depth-sensing cameras and looking in through eye-tracking will become a big part of helping feel a lot more connected to virtual interfaces…and maybe help real VR computing platforms seem a lot more possible.