When it comes to 5G networks, there’s something beyond pure speed to get excited about.

Next-generation mobile networks will be able to accommodate a lot more people and a lot more data as carriers like Verizon, T-Mobile and AT&T and manufacturers like Nokia and Ericsson improve the total capacity of the network. That means your phone won’t be fighting against all the others trying to send and receive data.

“Once 5G arrives on a nationwide basis, there is so much bandwidth available that we will have pretty much unlimited access to data,” predicted Forrester analyst Dan Bieler.

Now playing:

Watch this:

What the heck is a 5G network?

1:29

5G will indeed be able to send data faster than 4G — probably something like 10 times faster than the new advanced versions of 4G. But those peak speeds often exist only in ideal conditions. By contrast, 5G should be more reliably fast. In other words, you’ll still be able to update Facebook, send that email attachment and stream your favorite TV show, even in crowded areas like city centers and stadiums where today’s 4G networks often struggle.

5G stands for fifth-generation network technology, and it should transform our digital lives as profoundly as previous generational shifts. Back in the 1990s, 2G was mostly good enough for text only, but 3G opened up the world of photo sharing and 4G made streaming video practical. 5G won’t just boost reliability, though. It could also accelerate new technologies like augmented reality, help self-driving cars send time-critical messages to one another, and link to the network everything from pollution sensors to health monitors.

Coming sooner than you thought

5G networks are expected to arrive in 2019. The conventional wisdom is that the early examples will be for what’s called “fixed wireless” connections, bringing fast broadband to your house without having to dig a pesky trench for a fiber-optic cable. However, Qualcomm, a top maker of mobile chips and radio technology, insists 5G will come to your phone that year, too.

“What drove industry support is that global demand for mobile broadband continues to rise,” said Matt Branda, Qualcomm’s director of 5G technical marketing. “Things are lining up to make this a reality in 2019 in your smartphones.”

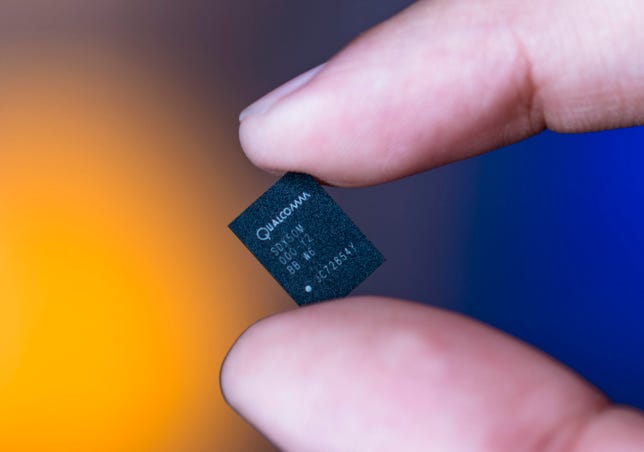

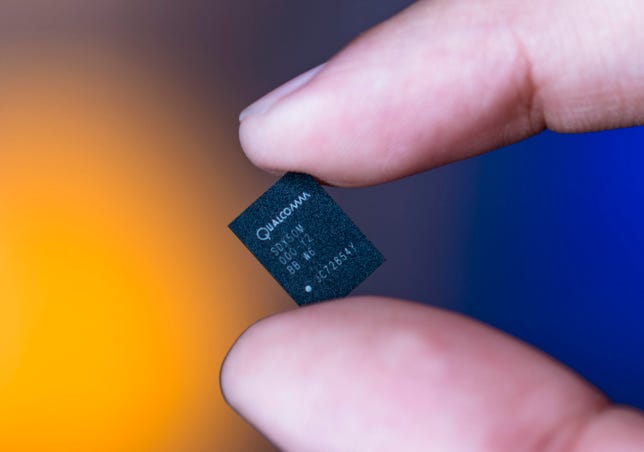

Qualcomm’s first 5G modem chip, which will let phones talk to 5G networks, now is working in prototype form.

Qualcomm

Qualcomm announced further progress Tuesday in Asia. Its Snapdragon X50 5G NR Modem, a chip for 5G phones, has made its first 5G connection. It was in carefully controlled lab conditions, but it was able to receive data at a gigabit per second, said Sherif Hanna, manager of 4G and 5G product marketing.

“Our intention is to put this into mobile devices and start testing them in the real world,” Hanna said, and Qualcomm expects the chip will reach 5Gbps data-transfer speeds.

If you’ve followed 5G networking, you may remember a promised delivery date of 2020. But the network industry have managed to speed up some parts of the standardization work. There are plenty of pilot projects, too. The highest profile likely will be the 2018 Olympics in South Korea, a country obsessed with super-fast networks.

5G network equipment will be expensive to install. Network operators will need upgrade all of their base stations, the central radio towers our phones talk to. They’ll also have to install more base stations for closer spacing and upgrade stations’ connections back to the main network. It’s worth it to the network operators, though, because 5G will let them satisfy our data demands.

“Delivering everything at a lower cost per bit motivates the operators to move to this system,” Branda said.

Matt Branda, Qualcomm’s director of 5G technical marketing

Stephen Shankland/CNET

How motivated? Brace yourself for a mind-boggling price tag. The industry will spend $2.4 trillion between 2020 and 2030, according to IHS Markit. In the US alone, spending will peak in 2023 with a whopping $23 billion spent.

What makes 5G tick

For a generational shift like 5G, engineers must figure out how to squeeze more use out of the existing airwaves. There’s only so much room in the radio-wave spectrum, and most of it’s already claimed. For example, some frequency bands are reserved for broadcast TV. Police get some other bands. And carriers spend billions of dollars to obtain government licenses for other parts of the spectrum.

But 5G taps into a new patch of the radio-frequency spectrum, the home of “millimeter-wave” radio signals.

“All this requires a scarce resource,” said Ulf Ewaldsson, a senior vice president at network equipment maker Ericsson. Radio spectrum is the “future oil.”

The oil boom started in places like Texas where you could drill a hole in the ground and money gushed out. As those supplies began to run out, oil companies pushed to harder areas like frozen arctic tundra and dangerous mid-sea drilling platforms. Similarly, radio broadcasts used the easiest frequencies first. The laws of physics make millimeter-wave radio communications tough.

For one thing, signals don’t travel very far because trees, buildings, your body and even the air can stop them.

Qualcomm is working on “millimeter-wave” 5G networks that tap into super-high frequency airwaves for sending data. These high-frequency radio waves struggle with obstacles, but Qualcomm says its technology is good enough to cover much of outdoor San Francisco even without adding new radio towers. This simulation is based on existing mobile phone towers.

Stephen Shankland/CNET

“You need direct line of sight” with nothing between the phone and the network base station it’s communicating with, said Ronan Quinlan, joint chief executive of antenna specialist Taoglas.

Engineers overcome some range challenges with “beamforming,” which tightly focuses radio signals in a single direction, but Qualcomm thinks it’s got another part of the answer. It can bounce radio beams off some structures like light poles and buildings.

5G will also continue to take advantage of plenty of easier-to-use spectrum. The fancy new millimeter-wave connections will provide a boost when available, but phones will also be able to fill in the gaps with more traditional radio technology.

Future feature delay

Accelerating the 5G delivery schedule sounds great. But that effort, announced in February, came at a cost. That’s because 5G is meant to hook a lot of devices to the network other than just phones.

Ulf Ewaldsson, a senior vice president at Ericsson, says 5G will meet its promise of 1-millisecond latency.

Stephen Shankland/CNET

“Speeding up the standardization process has forced the key stakeholders to pull out many features of the 5G laundry list,” said Stéphane Téral, an IHS Markit research director for mobile networks and carrier economics.

Among those delayed features are fast-response networks. Ewaldsson expects that a later phase of 5G will fulfill its promise of 1-millisecond latency, meaning that only a thousandth of a second passes between when a message is sent and when it’s received. That’s 50 times quicker than with today’s 4G networks, according to equipment maker Huawei.

That fast response will be important for future network uses such as self-driving cars communicating with one another and with infrastructure like traffic signals. Such a response time could let a human operator remotely control mechanical equipment. It could, likewise, open new vistas for virtual reality and augmented reality where equipment must respond nearly instantly to changing perspectives. It could also mean that service robots helping elderly people will be able to communicate fast enough with control centers to be useful, according to Nokia.

Another major area for mobile networks will be the internet of things (IoT). Think of attaching thousands of soil monitors on a farm to a network, or imagine a hospital with a massive number of monitors for medical equipment. 5G will require less power than 4G and will be easier on monitor batteries in these kinds of situations.

However, carriers aren’t generally experienced selling anything besides network access to mobile phones. There will be a learning curve for them to work with factories building 5G robots or with mines using 5G excavation equipment, Ewaldsson said. Still, all those future network customers are key to justifying the big upgrade expense for 5G.

“The biggest challenge for the industry is going to be opening up fast enough for the business case to work out,” Ewaldsson said.

Those fast-response networks and the 5G-based internet-of-things tech will arrive — just not as soon as those anxious for more radical change would have liked. For now, we’ll have to be content with faster, higher-capacity networks for our phones.

First published October 16 at 6 a.m. PT.Update, 6:30 p.m.: Adds news that Qualcomm got its 5G mobile modem chip working.